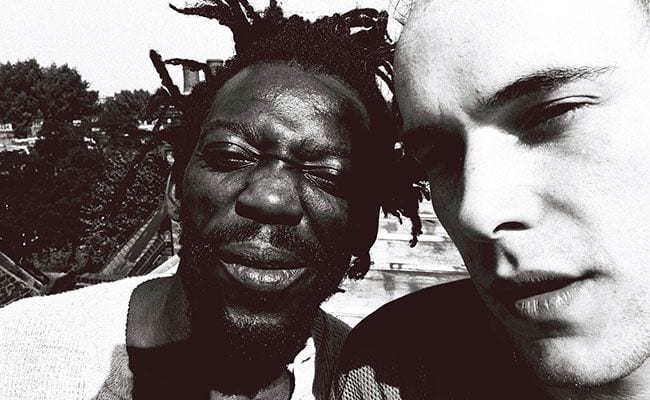

Adrian Sherwood’s contribution to modern music are many. His influence rises out of him unique melding of dub, African, Jamaican, and countless other traditions into the music that surrounded him, especially the post-punk and fledgling new wave movements. He has countless career moments worth recalling here, but his work as leader of African Head Charge still stands as some of his most challenging and rewarding music. The four African Head Charge albums — 1981’s My Life in a Hole in the Ground, 1982’s Environmental Studies, 1983’s Drastic Season, and 1986’s Off the Beaten Track — have all been reissued on vinyl for a new batch of fans to discover. Listening to them as a whole now is deeply rewarding, especially because they don’t feel like a progression so much as one long, unfolding, complex record, a complete and cohesive document that meshes experiments and structure, old sounds and new, and various musical traditions all into one heady mix.

If the title of 1981’s My Life in a Hole in the Ground feels still like a dig at Brian Eno and David Byrne’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, it’s mostly because the music sounds so much more resonant. The title was likely more a nod, but the sounds here are a sonic leap ahead of those other musical legends. The album doesn’t experiment so much as it challenges us. Opener “Elastic Dance” clashes production accents and keyboard crashes with the plain, organic pinging of a jaw harp. The harp gives way to pulsing psychedelics and a lean-persistent beat. The song never takes shape so much as it sets its pace and lets the bolts fly off the chassis in every direction. It doesn’t pin down its influences as clearly as other moments in Sherwood’s discography, but it lays out a palate the other songs can draw from.

Along with percussionist Bonjo Iyanbinghi Noah, Sherwood builds the rest of the album on unforgettable grooves. “Family Doctoring” builds its echoing shuffle on reggae structures, while the persistent hook that rises and falls through the track brings in Eastern textures. “Crocodile Shoes” lets Noah move through African rhythms, while the occasional howl or distant horn merely adds heft to his drums. “Far Away Chant” digs into the darkest, most haunting corners of dub, while “Primal One Drop” presents the kind of straight-on beat that hews closer to rock or R&B without losing its groove. It’s an album of strange sounds united by its beats, a lean record that still surprises with its flourishes but stays within the borders it sets up.

1982’s Environmental Studies starts to stretch those borders a bit. Opener “Crocodile Hand Luggage” feels like a natural next step. It’s got the same dark shadows of “Far Away Chant”, but the textures are far thicker here, the sounds more varied and clattering over the percussion. It also includes synth vamps that tap into vein of jazz-fusion that never quite leaves the record, offering yet another turn in the African Head Charge sound. Songs like “Snakeskin Tracksuit” and “High Protein Shack” nod more towards traditional jazz, with an emphasis on horns and syncopated rhythms, but any notion that Sherwood is settling into a genre gets blown up in the second half of the record. This is where get some full-fledged experiments, like the layered scuffling and snapping of “In a Trap”, or the Eastern-riffs-turned-kitchen-sink-drum-circle of “Breeding Space”. “Primitive” and “Latin Temperament” turn back to Jamaican and African hints in the drumming, but the echoed, sometimes scraped out production and oddball turns both recall dub and, perhaps, predict later movements like trip-hop (along with earlier track “Dinosaur’s Lament”.

So Environmental Studies built on its predecessor, delivering stranger turns but also a few more memorable moments. The next record Drastic Season, bedded down in the farthest corners of the sound from Environmental Studies. “Timbuktu Express” shimmers with thick layers of neon synth until those turn inside out, shifting into sinister pulses of vibrating noise. “Bazaar” and, later, “Fruit Market” still have their eye on reggae and dub, but around them songs erupt into strange, explosive shapes.

None are more arresting in their strangeness than “African Hedge Hog”, a song where everything stutters, where it seems the bass and drums can’t quite find each other, where the guitars seem borrowed from post-punk but get sliced up into unrecognizable, far-off bleats, where synths and horns seem to be shouting at each other like animals across some great, dark expanse of land. Environmental Studies, like its title implies, feels geographical, like it is more interested in playing in space than propelling forward. But, of all the albums, it also feels like the one most reliant on the others. It’s an interesting record, front to back, but its true feat is in setting up the next record.

That record, 1986’s Off the Beaten Track, changes things up a bit. It comes three years after its predecessor, and though Drastic Season was the first record the duo made in a proper studio, this is the record that finds them taking full advantage of those environs. Unsurprising perhaps that proponents of dub would find new strengths in a new studio space, but Off the Beaten Track continues to push the African Head Charge sound, but also manages to deliver those shifts in the pair’s tightest, most dynamic compositions to date. Check how effortlessly they match their love of Eastern melodies with dub and other Jamaican music traditions on the titular opening track. Hear how “Belinda” borrows a contemporary, industrial sound and meshes it with the duo’s trademark production scuffs, found sounds, and the organic backbone of congo drums.

“Throw It Away” shifts African Head Charge’s usual focus by pairing it with a more rock-based beat and turning out something that aligns more with the burgeoning hip-hop scene than any other song in their repertoire. “Release the Doctor” takes the often too-light elements of New Wave guitar and keyboard hooks and weighs them down with a perfect balance of deep rhythms and rippling production. Closer couches its haunting voices and deliberate pace in the duo’s heaviest textures, as well as natural sounds, as if in the duo’s final moments they simply drifted off into the world around them, into a pulsing, lively world they created.

These albums managed to mesh so much of their own past and present together, that it’s amazing how they don’t sound dated at all now. Instead, the albums echo nicely off of each other, each one adding some clarity and some complexity to the others around it. Adrian Sherwood stands as a long-time musical innovator, but his with Noah as African Head Charge is perhaps his most timeless and resonant work. These are records that preferred discovery over perfection, and the deep, undeniable beauty of the right sound over the quick hit of a good hook. Like so many notes that populate these four important records, African Head Charge is gone, but its influence echoes on.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)