“My words are like a dagger with a jagged edge / that’ll stab you in the head whether you’re a fag or les / or a homosex, hermaph, or a trans-a-vest / pants or dress, hate fags? The answer’s yes.”

—Eminem, “Criminal”

Here is what it meant to be a man if you were a certain type of boy in the United States: if you were, as I suppose I was, a child of the ’90s, an accidental legatee of America’s late-century traumas and shibboleths, moral panics and incidental neuroses; if you were, as I suppose I was, a son of the South, a student of flash floods and late afternoon cloud formations, whose happiness could be most intelligibly derived in the censored light of the sun, in the postdrome of a thunderstorm, in front of a rain puddle, wading an empty two-liter bottle with the Coca-Cola label scratched off, fishing for tadpoles; and if you were, as I suppose I was, a boy for whom melancholy could be said to “come easily”, a boy for whom softness and tenderness were not aspirational conditions but the general alignment, or what they now euphemize on MTV as a “creature of sensitivity”.

Here is what it meant to be a man if you were a certain type of boy in the United States and MTV had not yet incorporated into its Viacom production notes a habit of euphemizing you as a “creature of sensitivity”.

It meant: a debt to be paid, to be settled at a later date.

It was the last summer of the Clinton administration, and to a child whose understanding of the world had come almost entirely by way of comparison to a past pockmarked by absence — the absence of TV, the absence of refrigeration, the absence of civil rights — modernity seemed like it had more or less “worked out”: that humanity could stall here, and it would more or less stay the same. Any disappointment we might have about how the modern world turned out, well, we would just have to get used to.

My family and I had just moved from Alabama, where we had grown familiarly adjusted to the rhythms and contours of living in a small city, the gambol of church bells on Sunday morning. Houston had the unwieldiness of a casino floor at the Venetian at 11PM on New Year’s Eve, with the added qualification that nobody ever seemed happy to be there, wherever they were, at any given time. I watched them from the bus window (it was always a bus window) on Old Spanish Trail, coming out of the tattoo parlors, the secondhand furniture shops, the Fiesta Marts, the heat baking their skin into a uniform shade of umber. I waited for the day I would become an adult and trade places with them.

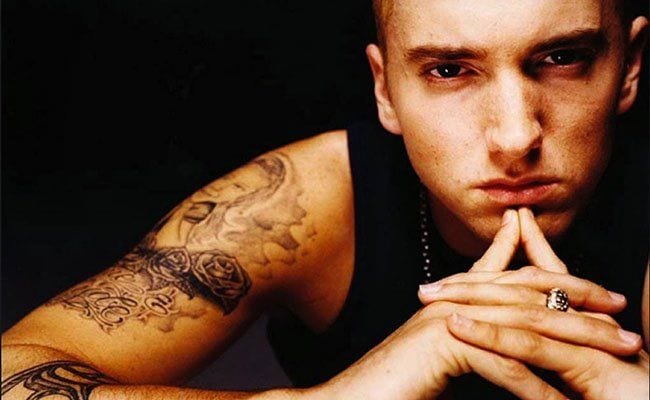

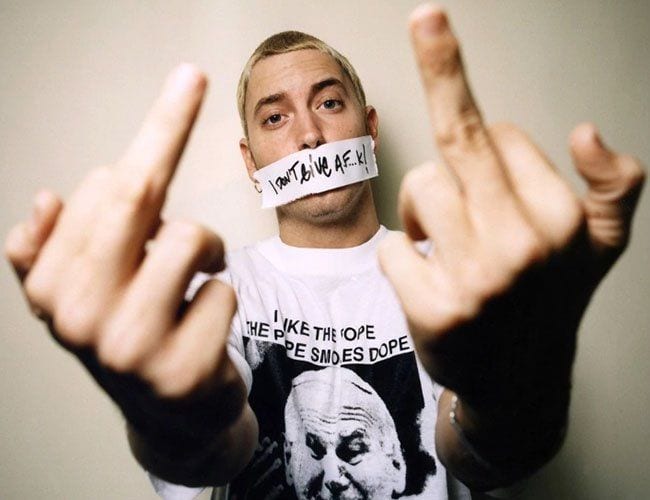

Accompanying me on those long afternoon bus rides would be a silver portable CD player, and a white CD emblazoned with a paragraph-long copyright notice, a pixelated image of a white man in a white t-shirt and a dark baseball cap, and the letter “E” printed in bold, large-point, Helvetica-family type; upside-down. With some effort I can also remember that these consumer goods had been purchased for me by my mother at Wal-Mart for the grand total of $50, or one-eighth of her weekly salary.

It occurs to me now how little of what we retain from childhood are the so-called “important things” are the appropriate highlights and annotations, is the so-called “point”: that the substance of nostalgia tends to have as its preeminent constituent mundane details, the way the sun bounces off the face of a clock in the living room as your father beats your mother in the bedroom, “trivialities”. For instance, a triviality: the man in the pixelated image on the front of the CD was holding in his hands what appeared to be a dark suitcase and a white plastic bag. Another triviality: “This is another public service announcement brought to you in part by Slim Shady”, was how the first track began. “Slim Shady does not give a fuck what you think. If you don’t like it, you can suck his fucking cock. Little did you know, upon purchasing this album, you have just kissed his ass. Slim Shady is fed up with your shit. And he’s going to kill you.”

The details are familiar. “Slim Shady” was born Marshall Bruce Mathers III to a 17-year-old single mother named Deborah Rae Nelson in 1972, would shuttle between working-class homes in Missouri and Michigan before spending the preponderance of his adolescence at 19946 Dresden Street, three blocks south of East 8 Mile Road, in a predominantly black neighborhood on the east side of Detroit. The details are familiar to us not only because “Marshall Mathers” is the name on the titles of two of his eight solo albums and “19946 Dresden Street” is the address of the house featured on the covers of both of those albums and “Deborah Rae Nelson,” as drug-addicted mother, is one of the leitmotifs that feature most prominently in his discography, with a starring role in one hit single (“Cleanin’ Out My Closet”) and direct shout-outs in at least two more (“My Name Is,” “Without Me”).

The details are familiar to us because in his music and in his album covers and in his public persona and in even the title of a 2002 semi-biographical film, and with a self-preoccupation that would strike us today as distinctly if not archetypically “millennial,” the details of Eminem’s life have been reconfigured into art: and his art, for the last two decades, has enjoyed a reverence and esteem within the famously conservative confines of our national culture that in many ways has been miraculous, even singular.

His 2000 album — or what I now understand to be his third, but which I cannot help but think of as his sophomore effort — The Marshall Mathers LP, is one of only four albums since 2000 to sell over 30 million copies (the other three are: Adele’s 21, a compilation album by the Beatles, and Eminem’s own follow-up to The Marshall Mathers LP, 2002’s The Eminem Show). He is, at the time of this writing, the best-selling male artist of the fledgling century.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

I was first introduced to Eminem at the age of ten by — although the term strikes me now as fundamentally dubious as any other impression I might have formed about the world at the age of ten — my first “friend” in Houston: a half-British, half-Japanese boy named, improbably, Clifford. Cliff challenged me, had a way with words that would take me a few more years to recognize as a way with words which had the consequence of coarsening certain defenses while seducing certain others into softening. “What do you think of Eminem?” I recall Cliff asking me one afternoon toward the end of science class, as our teacher busied herself with grading and we were left to our own amusement. I told him I did not know who that was.

“Don’t you listen to hip hop?” would be his next question, and I told him I did not. “So what do you listen to then?” he tried again, and I told him that I listened to a bit of everything. (I somehow had the foresight not to tell him that the most I knew about music was from the oldies station that our sixth-grade teacher sometimes had on in the morning before the bell rang for homeroom.) “Colson,” Cliff said, “let me offer you some friendly advice. When someone wants to know what kind of music you like, never tell them everything. Saying everything just makes it sound like you don’t know shit about anything. Now check this out,” he added, retrieving from inside his blue JanSport backpack a CD case. I looked at the CD cover, at the sepia-toned portrait of an artist as a young man sitting with his head lowered on the stoop of a clapboard house. “Now this shit,” Cliff whispered, looking into my eyes. “Now this shit is dope.”

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, Cliff’s voice carried enough of a British inflection to render faintly ridiculous his near-constant boasts about being “gangster,” about living in “the ghetto,” about sleeping with a “Colt Mustang” underneath his pillow and spending his Sundays at the “shooting range” with his father (although this last detail strikes me in retrospect as probably true). In fact, Clifford did not live in the ghetto but in a two-story townhouse about a mile or two from where I lived, in a lower-middle-class, predominantly Spanish-speaking suburb whose class and racial composition more or less mirrored that of my own apartment complex; I remember distinctly that his mother drove a Subaru. I mention this not to suggest that there is anything indecorous — or indeed, anomalous — about a sixth-grader engaged in the exercise of creating a persona; on the contrary, persona-building is and will remain, I think, the public exercise of our time.

But what bewildered me then, and what strikes me as relevant now, is how little Cliff’s Ready to Die persona earned him in the way of social advancement; is how inelegantly Cliff’s tastes in clothes and TV and music aligned with the prevailing social character of our middle school, the majority of whom lived in suburbs which were not predominantly Spanish-speaking, whose fathers took them to Little League on Sundays and whose mothers drove them to school in Land Rovers, not Subarus. It didn’t occur to me then that “being gangster” or that “living in the ghetto” or that “sleeping with a Colt Mustang” underneath one’s pillow could have as its starting point a presumption of insolvency in any contest in which “wealth” or “whiteness” or “conversancy with upper-middle-class rituals” would be the determining factors; could have as its ambition something more vital and elemental than social success as a sixth-grader at T.H. Rogers Middle School.

I have here one annotation I seem to have retained from childhood: that ten is the age by which most of us, if we are cynical enough, will have “come awake,” will have begun to look outside of ourselves and at each other in earnest to figure out what would be celebrated in this life, and what would not. We will understand with some clarity, for instance, by the age of ten, who the pretty girls are in our classrooms, and why that matters. We will understand with some clarity, for instance, by the age of ten, what sort of boy will be picked first, and last, for kickball, and why that matters. “Stop being such a little pussy, Colson,” was a sentence I would hear in my head, in Cliff’s voice, whether he was with me or not.

The Company We Keep

It occurs to me now that so much of what I want to talk about here is what Cliff had already figured out, by the age of ten, would be the “long game”; is the apprehension of some looming contest that would inevitably cast a shadow, however intangibly, over each and every American male’s experience of boyhood: so long as he knows, from the images we diffuse, of the prizes certain men will reap, precisely to what degree masculinity will be rewarded in this society — and so long as he knows, from the images we diffuse, of the trials certain men will suffer precisely to what degree its absence will be punished.

I was 11-years-old when they first started calling me a faggot, when both the physical artifact of the word — two syllables, spat rapid-fire, followed usually by laughter — and the stain of malformation it transmitted became part of the donnée, not an unsettling gust of wind but the given of my social experience. I was a quiet child, reclusive in temperament but with an interest in long, ambulatory conversations, like the kind I used to have with my pastor in Alabama before I secretly lost my religion.

Her name was Emmeline — not the pastor but the 11-year-old girl who first called me a “faggot,” in a pique of anger or annoyance, something about my unwillingness to evacuate a bus seat. I had been called other names before — some of them unpleasant, some of them merely descriptive — but the word “faggot”, I remember, struck me as particularly strange-sounding and exotic, tropical in origin. “What does that mean?” I asked her, and I remember Emmeline, as the boy next to her giggled flamboyantly, looked down at her lap, closed her eyes, and said: “A bundle of sticks, Colson. That’s what you are. Are you happy now? You’re a bundle of sticks.”

It was the melody of nursery rhymes, lollipops and children’s clapping games — akin to “one a-penny, two a-penny / hot cross buns” — that I found myself sinking into on the bus after the flush on my face had disappeared, and Emmeline and the boy next to her had settled into a conversation about who wore what and went where and with whom, the coterie of childhood. I wore over-the-ear headphones and tried to hold the CD player steady in my lap, anxious that any of the ridges on the pavement of the thoroughfare would be the one to cripple my CD player for good: most of the words I absorbed I understood dimly were not “age-appropriate” and could make out as individual units, but could not cohere into intelligible verses or sentences.

Had I been able to, they would have cohered into this: “And whether you like to admit it, I just shit it better than ninety percent of you rappers out can, then you wonder how can kids eat up these albums like Valiums, it’s funny, ’cause at the rate I’m going when I’m thirty / I’ll be the only person in the nursing home flirting / pinching nurses’ asses while I’m jacking off with Jergens / and I’m jerking but this whole bag of Viagra isn’t working / and every single person is a Slim Shady lurking / he could be working at Burger King / spitting on your onion rings / or in the parking lot circling, screaming ‘I don’t give a fuck’ / with his windows down and his system up”. All I remember today is loving every single minute of it.

You will recognize an irony here, perhaps categorize it into one of the many ironies that make up that so-called tapestry of life’s hard-earned wisdom, or that private hell which every American adult clandestinely remembers as the absurdity of adolescence. I do not. I remember as a child being preoccupied with the question of whether God had any special insight into our intentions. It struck me, even at the age of ten, but especially by the age of 11, that there was a distinction to be made between the atrocities born of “anguish” and the atrocities born of “ambition”: between Mr. Freeze and the Joker. (It strikes me only in retrospect, as a 27-year-old adult, that this is a distinction that can be in all cases dissolved entirely.)

Track 14 of The Slim Shady LP. Track seven of The Marshall Mathers LP. The line in track five that asked, “How much easier would life be if nineteen million motherfuckers grew to be just like me?” These were sentiments that could penetrate all but the most impermeable age and language barriers. It struck me, in other words, even at the age of ten, but especially by the age of 11, that what little I could discern from Eminem’s music in the way of intelligible thoughts and sentences, were intelligible thoughts and sentences which had been born — unambiguously, unashamedly, and with the neurasthenic exhilaration of a lifelong outcast suddenly flying too close to the sun — out of sadness.

He was the poet laureate of teenage insubordination, an astonishing late-’90s prefigure of white male resentment, and — assuming you choose not to close your eyes to the degree to which his childhood and adolescence were informed by a series of circumstances felt disproportionately by Americans not of his race — the white prince of black anguish; and the problem was that “nineteen million motherfuckers” were growing up to be, if not just like him precisely, then enabled by the cultural miasma of which he was a vital constituent to take for granted that this is what American manhood is. The last thing I would like to say is that this is not what American manhood is. There has been some confusion, it seems, on some corners of the Internet, and presumably in some corners of the real world, that all people on the Internet will at some point retreat into, about what exactly anger is.

Anger is sadness.

Barring a handful of his radio singles and a smaller percentage of his album tracks, it strikes me as improbable that anyone should listen to Eminem’s discography today and not be struck by what is above all, first and foremost, one of popular music’s most prolonged and extraordinary expressions of interminable — which is to say, resistant to fame, fortune, and the friendship of Elton John — sadness. It strikes me as equally improbable that anyone should familiarize themselves with the complaints of, say, “men’s rights activists” — or for that matter Elliot Rodger, the 22-year-old college student who, in 2014, murdered six people in California before leaving behind a 107,000-word anti-female manifesto — and not be able to isolate the same substrate.

That sadness slides all too quickly into despair, slides all too quickly into self-victimization and finally all too quickly into the nihilism that despair and self-victimization together enable, is a phenomenon understood by many people intuitively, but that not many people have identified as operative in a wide array of cultural artifacts — of which Eminem’s music is one — that seem to suggest some recombinant of victimhood, insubordination, and transgressive reprisal constitutes what it means to be a man; and that what it means to be a man should furthermore occupy a place of prestige and high repute in our culture. It does not, and it shouldn’t.

Victimhood — at the hands of his mother, at the hands of his critics, at the hands of his ex-wife, at the hands of our culture, at the hands of a childhood tormenter (who in 1999 told Rolling Stone: “We flipped him right on his head at recess. When we didn’t see him moving, we took off running. We lied and said he slipped on the ice,” and who two years later sued Eminem for defamation after being named in a 1999 song about a similar incident) — lies at the black heart of Eminem’s music, functions as the mise en scène against which the brutality of his alter ego’s descent into nihilism and madness might be fathomable, even forgivable, culminating most garishly in the transgressive glee with which he mimics his then wife’s dying sobs and asphyxiated pleas (“Go ahead, yell! Here, I’ll scream with you! Somebody help! Don’t you get it, bitch? No one can hear you … Now bleed, bitch! Bleed!”) on “Kim”, the third-to-last track of The Marshall Mathers LP.

“I had asked him before the show if he was going to play that song, and he said no, because I know you’re going to be there and I wouldn’t do that to you,” Kim Mathers told 20/20 in February 2007, recalling the night her husband performed “Kim” in front of 17,000 people at the Palace of Auburn Hills on 7 July 2000. “He was using a blow-up doll to reenact like, me being choked … like for him to do that in front of thousands upon thousands of people, knowing I’m out there and just watching everyone else singing the words and laughing and jumping around in like, approval of — just, I couldn’t take it. I immediately left after that, you know. I got into a car accident on the way home, I was so upset. And uh, I made it home and I just, I could not gather my senses, I just. I went upstairs to my bathroom and I slit my wrists.” Mathers was treated that evening at a hospital near the couple’s home in Sterling Heights, Michigan, before being transferred to a psychiatric ward, according to a BBC report published at the time, for “observation.”

A month later, Eminem filed for divorce.

“Everything he did for, you know, me and the kids, he had to be praised for,” Mathers said, reflecting on their marriage. “He’s so used to getting so much attention, people praising him for his work, that he expects that when he come home and it’s just — I don’t look at him like that, you know? I’m not putting you up on a pedestal. You’re not that person to me.” Soon after his ex-wife’s appearance on 20/20, Eminem filed a motion with Michigan’s Macomb County Circuit Court to prohibit his ex-wife from making “derogatory, disparaging, inflammatory and otherwise negative comments” about him. “We’re happy the court was able to bring this matter to a just and equitable resolution,” Eminem’s attorney told reporters outside the courthouse on 26 March 2007.

That a presumption of “victimhood” has come to underlie the self-understanding of a minority class of men who will go on to profess, as an article of faith, an allegiance to the principles of self-reliance, self-ascension, and the heroic rejection of all ideals which did not originate from one’s own (presumably transgressive) account of what it means to be a man is a phenomenon in which you might have once again deduced an irony. I do not. Antibiotics are widely understood to remove only certain sensitive strains, leaving behind a minority class of drug-resistant variants that become, predictably, the dominant subject of all medical literature on bacteria. It occurred to me in the course of writing this piece that an analogous principle has been operative, at a cultural level, on ideologies as well.

What We Shame in Our Culture Matters

Ideologies are culturally diffused, are culturally suppressed. (In fact the most insidious myth about ideological freedom in the Western world today is the myth that its greatest barriers are somehow legal in nature: they are not. The greatest barriers to ideological freedom in the Western world today are the disincentives mediated by informal institutions, our private connections, by the company we keep.) The cultural suppression of racism or misogyny or religious fundamentalism of all stripes can in each instance only “do so much” — which is to say, what remains will inevitably retreat, reconstitute, evolve structural defenses. And here is where transgression comes in. By far the most reliable appeal of any ideology whose time has otherwise passed is that secret thrill of transgression, or so-called “ideological independence” (often but not always concealed by a varnish of victimhood), is the fundamental seductiveness of being David to modernity’s Goliath.

I did not see in my lifetime, having come along in the aftermath of feminism’s unfolding triumph across the Western world, the remarkable docility with which the masculine ideal is reputed to have evolved from the urbane chauvinism of Rick Blaine to the urbane liberalism of Ryan Reynolds. But I have seen in my lifetime the emergence of a resistance to that evolution, and an aspirational reclamation of the old order. And to the extent that this reclamation embraces a resistance to cultural instructions that unnecessarily hamper human freedom, I might even be all for it. Edward Snowden is transgressive. So, too, was Bradley Manning. So, too, was Bruce Jenner. But to the extent that this reclamation embraces a sociopathic indifference to the consequences of one’s life — under the banner of so-called “self-ascension”, under some delusional vision of “manhood” — well then, we are no longer in the territory of men, but of a certain breed of teenage boy.

We are in the territory of Slim Shady.

An indifference to the consequences of one’s life, while by no means exclusive to the male gender, is the hallmark of “sociopathic masculinity,” and here I will admit an irony: is the antithesis, too, of any sane construction of what it means to be a man. And yet this condition is observable in such a wide array of delinquencies perpetrated disproportionately by a single gender — from terrorism to spree shootings to violent crime overall to the rate at which fathers in this country are known to abandon their offspring — that one finds it bewildering that a society which has otherwise demonstrated an intuitive fluency for pattern recognition when it comes to identifying antisocial tendencies within certain religious and ethnic minorities has not yet arrived at the conclusion that, with regards to violence, what might merit further study is not so much the state of society in general but the state of masculinity in particular.

And yet the state of masculinity in particular, for one reason or another, slips under the radar every time.

To draw this point more finely: imagine that on the one hand we have a religious sect homogenized by both in-group and out-group shaming (“A bundle of sticks, Colson. That’s what you are.”), whose principal derivatives of social capital are physical and sexual “ascendancy”, in-group and out-group “dominance”; and on the other, data suggesting that members of this sect are, by a factor of at least two, and in one case 88, more likely to engage in all 30transgressions identified by the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting bulletin as criminal offenses with the exception of “larceny-theft”, “forgery”, “fraud”, “embezzlement”, and “prostitution”; and a society that is having trouble putting two and two together. What I am trying to say is that what we shame in our culture matters. What I am trying to say is that we cannot celebrate certain qualities in man and not expect to create a fair number of men who are fundamentally inwardly-directed, who are instinctively indifferent to the consequences of his life, so long as his life points him upwards,so long as he himself is ascendant.

It occurs to me finally that sociopathic masculinity is in all cases identical to the ethos of the adolescent: an abandonment of the responsibility to do right by other people, to do right by the world which seven billion people are at the same time trying to share and inhabit. Of course, you and I can argue until we’re blue in the face about what it means to “do right by other people”, but that is exactly my point. I am talking here about a strain of people to whom it no longer occurs that there might be a difference.

Masculinity, as opposed to man, has at its center not a soul but an ego.

This is not to say that biology doesn’t have its role, not to deny the diversity of traits and impulses and predilections that can trace their turbulent headwaters to some common or uncommon variant in the human genome. It is simply to say that whatever the environment incentivizes on top of that, it does so by appealing to some common vision of what it means to be a man: it does so by appealing to ego. It is not man’s soul but his ego that deadens his emotional sensitivity, unnaturally handicapping his capacity for self-knowledge, the ability to name or even draw distinctions between the viscera of his disintegration. It is not his soul but his ego that veers him inexorably toward violence, aggression, a fulfillment of the death instinct.

I know this to be true at the age of 27, but I did not know this to be true at the age of 11, as I found myself staring into the muzzle of a small black handgun, into the black heart of a t12-year-old boy’s ego. “You’re not afraid of guns, are you?” I remember Cliff laughing, pointing at my stomach a Glock he had retrieved from his parents’ bedroom while his parents were out running errands, and Cliff and I were in the living room, not “doing homework” but eating Slim Jims and watching South Park. It is a memory that at last defies all explanation.

“Come on, put that down,” I remember saying to Cliff, and when he did not I remember tears collecting in my face, which I now understand must have only made it all the more exciting for him to raise the tip of the gun to my eyeline, to point the barrel of the gun directly in between my eyes. I recall telling myself that the operative danger here was in becoming a “statistic.” I recall trying to summon from the morning papers a statistic about the rate at which guns accidentally discharged in the hand, the rate at which jokes between adolescent boys turned catastrophic. I recall being unable to.

“Don’t be such a drama queen. I’m not going to shoot you,” were the 12 words that ended the standoff, that coaxed my heart into resuming a cardiac cycle. The punchline, depending on how you “look at it,” belongs to the boy holding the gun, or else the boy whose brush with mortality came at the hands of an arbiter whose fingers were routinely red with the dust of Hot Cheetos. In fact, the older I get the more acutely I am aware of living in a society that at last seems no longer to know how to look at its men.

To be no longer a child is to understand that every feature of the world is provisional, that all arrangements are open for reconsideration, that there is nothing unconditional about how the world of human beings has settled, for better or for worse, which can’t be evicted from its bearings. I remember as a child acquiring — from MTV in particular, but Hollywood more generally, that cultural miasma manufactured in California and administered to the rest of the country by an economy of scale, not to mention sheer force of will — an intuitive understanding of femininity in men as something to be mocked, humiliated, diminished: MTV now, I hear, drapes its logo in rainbow swatches at the stroke of midnight on the first of every June.

Cliff now lives in Austin, and has, if his self-presentation on the Internet is any indication, heard the cues of the 21st century, has become a man mindful of the edicts binding the urban millennial male: gay marriage is a no-brainer, the Trump presidency a non-starter. Eminem, too, has heard the clarion, telling Rolling Stone 13 years after The Marshall Mathers LP: “The real me sitting here right now talking to you has no issues with gay, straight, transgender, at all. I’m glad we live in a time where it’s really starting to feel like people can live their lives and express themselves.”

I wonder if these evolutions taken together amount to anything more than the observation that adolescent boys, in our herculean efforts to make sense of our aridity, do grow up. And then I wonder if I have. What does it mean to “love” Eminem anyway, if my most vivid memory of Eminem is not of any particular lyric, but of coming across one night on the Internet, at the age of 12, a gallery of images taken from the set of his latest music video, including two or three in which he is completely naked, closing my bedroom door, and masturbating furiously? It means, I think, nothing more or less than this: that I am thankful to have found him when I did, and I am equally thankful, but with a melancholy that makes it right now difficult to speak, that his time has passed.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)