The original Fleetwood Mac and Humble Pie fit the post-Jimi Hendrix milieu of hard ‘n’ heavy British blues rock bands, but both had deep roots in the British music of the 1960s. In the wake of psychedelia, rock music was now the subject of serious cultural scrutiny, but in 1969, many trends continued in the five years since the British beat boom exploded onto the scene. Five years on from Beatlemania, Humble Pie leaders Steve Marriott, originally of the Small Faces, and Peter Frampton, originally of the Herd, were being chafed by their simultaneous identities as ambitious musicians and as teen idols. Five years on from the Rolling Stones debut, Fleetwood Mac guitarist Peter Green, bassist John McVie, and drummer Mick Fleetwood had come out of John Mayall’s legendary Bluesbreakers to be up against fellow Bluesbreakers alums in a new generation of British blues.

Also, five years after Bob Dylan‘s arrival in the British charts, the folk-rock group Fairport Convention would cover three of Dylan’s songs for their album Unhalfbricking, released in July of 1969. The band would record Liege & Leif only five months later, based on six rocked-up arrangements of British folk standards. Rock music was supposed to be exciting and electric, but far from being a reactionary step, the lyrical themes of these historical songs would chime with concerns of the 1960s counterculture. British folk would be a key touchstone for the new generation of so-called progressive rock bands, whose ambition would carry these countercultural ideals into the following decade.

The continuing transatlantic success of Britain’s top groups had given many at home and abroad the sense that London was now the center of the world. The critic Geoffrey Cannon would collate the impressions of the cultural elite in correspondence for The Guardian newspaper. Said one German A&R man, “I come to London every four weeks to get my hair cut and to breathe your air. Everyone in London is free; everything is possible.” One Parisian music journalist said, “I envy you. In London, you can do anything. Everyone is on the scene; everything’s moving.” The iconic American singer Janis Joplin would confide that, in Cannon’s paraphrasing, “Britain was the home of blues, the place where the original Black American blues singers got their first and best appreciation.”

Britain had their groups. It also had a network of niche recording labels like Blue Horizon, founded in 1965 to release the works of American blues artists and which by 1967 was recording home-grown blues rock acts, and underground magazines like International Times, launched in 1966 at a psychedelic happening also featuring Pink Floyd. However, the domestic media industry was constrained by a dominant and conservative public broadcaster, only three TV channels, and no independent commercial radio. America was still the world’s biggest market and the driving force in an entertainment industry encompassing music and movies. America had Hollywood and Motown. It also had the Monterey International Pop Festival and Rolling Stone magazine. While its writers remained in love with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, there were rumblings of discontent against those newer British bands who continued repurposing American music. Fairport Convention’s journey would be emblematic of British popular music at a crossroads.

The blues, however, would remain the lifeblood of rock. Beyond the continuing success of the Rolling Stones, the most enduring story of British blues rock was the remarkable run of guitar heroes to emerge from the Bluesbreakers and the beat group the Yardbirds. For a group whose original specialty had been rave-ups, the drawing out of Chicago blues standards to include exciting if rudimentary instrumental soloing, it was apt that the guitarists who passed through the Yardbirds would go on to form the grandiose likes of Cream and Led Zeppelin, and lay much of the groundwork for what became heavy metal. While these groups were hot on the charts and in the press, the more traditional blues revivalists, such as Chicken Shack and Ten Years After, were equally popular with British record buyers.

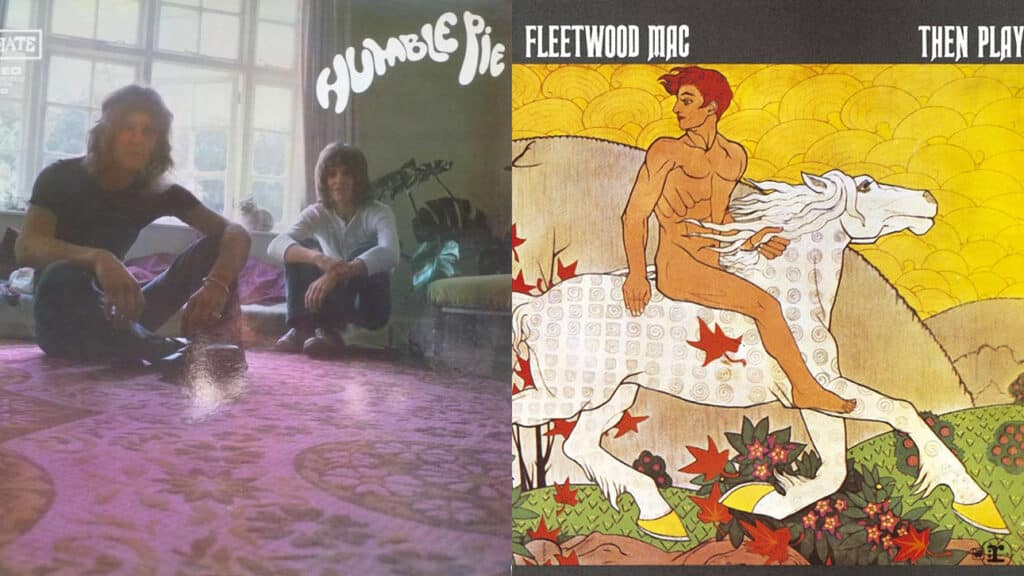

Over the years, blues rock would arguably become the most vilified style of popular music, an easy target for its presumed inauthenticity. First, there were the progressive rock musicians who dismissed its unsophisticated charm. Then, there were the punks who scorned its unwavering commonality. Then there were the neoclassical metal virtuosos who couldn’t appreciate its formidable sloppiness. Even by 1969, there were murmurs of critical dissent. Geoffrey Cannon, who in 1964 had fretted that “what no pop group has yet done is obtain the musico-emotional depth of blues in songs which concern British youth” would further demur upon this latest incarnation of “the British blues bands, a fuzzed, directionless, complex sound, semi-orchestrated, with little personal characteristic apart from guitar solos.” Fleetwood Mac’s Then Play On and Humble Pie’s Town and Country, both released in 1969, would see both bands trying to break beyond their respective constraints.

To some, Then Play On’s reputation is built on how, in the words of John Morthland’s 1969 Rolling Stone review, “tired of being another British blues band, the group has said goodbye to Elmore James and is moving into the pop-rock field”. Specific songs on Then Play On have been variously described as folk rock, psychedelic rock, or progressive rock. Taken as a whole, it remains a blues rock record, but one with an ambience closer to country blues than the more prevalent urban form. It is an album that requires several listens to appreciate. Morthland would superficially characterize the record as “slow and wandering – instruments in search of an idea”. As a blues rock record, it expectedly lacks any irrepressible melodies, but for the most part, it also lacks raucous riffs and rhythms of electric blues. The hooks come in the form only a deep blues lover might appreciate, such as the sublime slide guitar on “Showbiz Blues”, or the hypnotic call-and-response of “Coming Your Way”.

One reason for the album’s lack of hooks is that so many of Peter Green’s best songs would be released as singles. The band had originally been signed to Blue Horizon, the independent label which catered to blues purists. Early in 1969, Fleetwood Mac would transfer to Immediate, another British independent, which by this time was in a financially precarious situation. So Fleetwood Mac moved once again to the American label Reprise. Blue Horizon and Immediate would each release one single, and Reprise would release three, each one a Peter Green song and all songs Green had written while preparing for Then Play On.

If not for the heady ambitions of rock music in the late 1960s, Peter Green could have been one of the great pop writers of his day. Each single has a hook, whether it is a melody, a riff, or even an atmosphere. The soothing instrumental “Albatross” was released first on Blue Horizon, with its glistening guitar passages and pulsing rhythms. Released on Immediate, “Man of the World” was a haunting singer-songwriter piece with one of the most gorgeous melodies of the time. Then, on Reprise, came the rambunctious rock ‘n’ roll of “Oh Well”, with sharp lyrics and catchy call-and-response guitar licks. Reprise’s second single was “Rattlesnake Shake”, a greasy funk shuffle which oddly enough was included on Then Play On. Finally, there was the mystical hard rock of “The Green Manalishi”, with its epic proto-metal guitar riff.

When label demands were all fulfilled, Green was left with three songs, in addition to “Rattlesnake Shake”, each a work of intricate and haunting beauty. Had “Man of the World” been included on Then Play On in place of “Rattlesnake Shake”, then it would have formed a suite alongside the subdued “Close My Eyes”, the weary “Showbiz Blues”, and the foreboding “Before the Beginning”. Of “Man of the World”, Green would say, “It’s a sad song, so it’s a blues, but people will say it’s not because it’s not a 12-bar. It’s very sad, it was the way I felt at the time. It’s me at my saddest.” At a time when ambitious rock musicians were being encouraged to look outward, such candid introspection was something novel. As is known in retrospect, Green was experiencing turmoil, which would result in his leaving Fleetwood Mac. His lyrics are shrewdly masked by the storytelling tropes of blues and pop, telling of lost love as an allegory for a deeper spiritual void.

Even “Rattlesnake Shake”, an obvious ode to onanism, was graced with some confoundingly capricious guitar licks and lyrics that plied the theme of rejection while slyly challenging popular music’s chauvinism. Bad taste machismo proliferated in the lyrics of the blues rock bands. Consider songs such as “Stray Cat Blues” by the Rolling Stones, “The Lemon Song” by Led Zeppelin, or “Wild Indian Woman” by Free. Rattlesnake Shake subverts these conventions. Its first verse opens in the voice of a man wooing a woman for sex and closes with a note of ambiguous dejection. By the opening of the second verse, the solicitations have become more direct, but it is revealed that this passage is a soliloquy; the narrator resigned to vent his frustrations through self-abuse.

For the listener, the tension of Green’s somber suite is broken by several instrumental jams. “Fighting for Madge” and “Searching for Madge” sound as if they were spliced up from the same spontaneous performance, but on the original vinyl release of Then Play On, would have sat in the middle of each side of the record. They are each superlative, feisty 1960s rock jams, though subject to some haphazard post-production on the cutting room floor. “Searching For Madge” includes an apparent easter egg, a sudden snippet of symphonic music that may or may not have been Fleetwood Mac’s version of “Revolution 9”.

It is a band trope with Fleetwood Mac that despite being the band leader and spokesman, Peter Green downplayed himself to the extent of naming the group after his bandmates Mick Fleetwood and John McVie. Green was 23 at the time of recording Then Play On, but guitarist Danny Kirwan, 19 years old and the newest group member, contributes the majority of its songs. What really comes through from the songs themselves is that Green was mentoring Kirwan in the manner in which John Mayall, 34 years old at the time of Green’s stint in the Bluesbreakers, had mentored him. Kirwan’s contributions brought a tenderness to soften Green’s angst, and his songs are typically musically accomplished, stylistically varied, pastel-rendered companions to Green’s compositions.

Kirwan’s uncharacteristic album opener “Coming Your Way” is driven not only by its blues-influenced call-and-response guitar riff but by Mick Fleetwood’s propulsive percussion, and with its epic instrumental outro, it matches the drama of “The Green Manalishi”. Meanwhile, “My Dream” is a gorgeous, gorgeously simple “Albatross”-like instrumental. “Like Crying” is a nimble ditty that rollicks along like “Oh Well”, while its lyric is a humorous and rather subversive take on sexual politics in the manner of “Rattlesnake Shake”. It also features an uncommon vocal duet between Kirwan and Green. On the face of it, Fleetwood Mac were a twin guitar band in the urban blues tradition, but for Then Play On, both guitarists would frequently work independently, refining their creations with the aid of improved multi-track recording capabilities.

Such technological advances throughout the 1960s were an essential part of shaping the sounds of its music. Improvements in amplification technology in the middle of the decade would bring about the power trio embodied by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, allowing for greater power and flexibility in performance. Back in the studio, further developments in recording technology would enable Hendrix to create layered symphonies of guitar rock while rarely needing a second guitarist. On Then Play On, Peter Green would achieve an effect closer to a chamber orchestra, sometimes layering and often sequencing guitars, as well as using a six-stringed bass to create sometimes subtle, sometimes dramatic shifts.

In contrast, Humble Pie’s greatest early strength was their cohesion. The band was touted as a supergroup, as each musician had prior professional experience. Also debuting in 1969 was the supergroup Blind Faith, featuring Eric Clapton on guitar, Steve Winwood on keyboards, and Ginger Baker on drums, each of them perhaps the most acclaimed instrumental virtuosos in Britain at the time. Humble Pie could not realistically match the hype of Blind Faith, but extravagance was anathema to their style. As Steve Marriott would explain, “Both Peter and myself have been pushed out to the front of our groups and wanted to break out.”

The band name derived from an English idiom, much like in Fleetwood Mac, made clear that each member in the group was equal. Marriott and Peter Frampton were both gritty vocalists adept on guitar and keyboards and could interchange fluently for what their songs required. Their rhythm playing could often feature inventive harmonic choices, while their lead lines were short and sharp and often interacted directly with the vocals. Bassist Greg Ridley was also a singer who could partake in three-part harmonies, and his rich, intertwining bass lines were mixed prominently alongside the guitars. Jerry Shirley was a drummer whose primary concern was to serve the song.

Humble Pie were signed to Immediate, the same label that had briefly been home to Fleetwood Mac. Run by ex-Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, its motto was to be “happy to be a part of the industry of human happiness”. The label’s casual administration and ensuing financial difficulties would mean that no singles were released in association with Town and Country, and distribution was limited. This would factor in the hostility of contemporary critics and the band’s muted legacy. Listeners would discover the records in a different order to their original release, distorting the band’s development and robbing them of their due in the rise of hard rock. A notorious 1970 Rolling Stone review of their A&M Records debut would label Town and Country as their UK debut when it was their second album of 1969.

In that Rolling Stone review, Mike Saunders would describe Humble Pie’s harder-rocking first album, As Safe as Yesterday Is, as the work of “a noisy, unmelodic, heavy metal-leaden shit-rock band”, words so pungent that they were later cited among several possible origins of the term heavy metal. Of course, the term had already appeared in the lyrics to the Steppenwolf anthem “Born to be Wild”, featured on the soundtrack to the 1969 film Easy Rider, and whose rhythm Humble Pie would borrow for the As Safe as Yesterday Is the song “Buttermilk Boy”. Town and Country, by contrast, was regarded as “quiet and basically acoustic and well produced by Steve Marriott. And boring.”

Easy Rider, released in July 1969, and its freewheeling soundtrack of Californian acid rock could have inspired the recording of Town and Country. Its story of maverick bikers who journey from Los Angeles to New Orleans for Mardi Gras is loosely echoed in Marriott’s curious yarns about being an outlaw in Abilene, Texas, or journeying down the Louisiana Bayou in the companionship of a Mississippi queen. Marriott’s imagination is matched with vivid playing that’s far from dull. “Down Home Again” packs the tastiest, warmest electric lead, playing into less than three minutes. “Every Mother’s Son” is built on a foundation of punchy acoustic guitar, with Frampton’s electrified lead interacting with the vocal rather than taking solos. “Silver Tongue” is the album’s most densely recorded cinematic track.

Marriott’s reluctance to write straightforwardly melodic songs and his abrupt shift from the cheeky Cockney persona of the Small Faces hit “Lazy Sunday” to the escapist Americana of “Shakey Jake” was all part and parcel of his attempt to reinvent himself as a serious musician. He envisioned Humble Pie as “a group where we could play what we wanted, and not what others wanted from us. We haven’t got to stick to anything made a hit.” With his lyrical songs and distinctive chord progressions bearing the influence of folk and jazz, Peter Frampton tempers Marriott’s intransigence. “Take Me Back” is dominated by an ascending vocal melody over a shifting acoustic guitar accompaniment. “Only You Can See” is based on a deceptively unsettling sequence of major/minor chord changes. “Home and Away” is an ebullient album closer, which flaunts the band’s triple harmony vocals and a coda that allows for some climactic instrumental interplay.

Then Play On and Town and Country ultimately stand as two records whose legacies have been shrouded by the mists of time and downplayed by the subsequent tragedies and renewals that affected the musicians involved. Then Play On belongs to a fine lineage of blues-inspired rock recordings, a peaceful resolution to the fiery experimentation of Cream’s Disraeli Gears from 1967 and Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland from 1968. Its haunting depths would resonate in the acoustic songs of Black Sabbath, while its atmospheric and lyrical darkness is an unacknowledged precursor to the dark wave currents of post-punk.

Town and Country contrasts compellingly with Jethro Tull‘s 1969 album Stand Up, which combined a similar mix of earthy folk and hard rock but in a way that seems quintessentially British. It also compares favorably to more successful contemporaneous roots-rock albums such as Elton John‘s Tumbleweed Connection from 1970 and Rod Stewart’s Every Picture Tells a Story from 1971. There is a timeless quality to the warm guitar and keyboard tones that it and other records like it achieved, which would invigorate the British and American trad-rock movements of a quarter-century later.

Mick Fleetwood once remarked of Peter Green’s abrupt departure: “If Peter stayed in the band, we could have been Led Zeppelin.” The same could have been true of Humble Pie. Ultimately, both bands were, on their own terms, a part of the progressive 1960s ethos, which carried successfully into the next decade and beyond.

Works Referenced

Eldridge, R. (1969) “Fleetwood Mac: Sold Out? Gerroff!”. Melody Maker. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

Morthland, J. (1969) “Fleetwood Mac: Then Play On (Reprise)”. Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

Welch, C. (1969) “Exclusive! Marriott & Frampton present HUMBLE PIE”. Melody Maker. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

Saunders, M. (1970) “Humble Pie: Town and Country; As Safe As Yesterday Is; Humble Pie”. Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

Cannon, G. (1968) “Why Isn’t London Jumping?”. Oz. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

Cannon, G. (1969) “Union Jack Blues”. The Guardian. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)