(Vertigo / DC Comics)

Nothing serves as a convenient rallying cry quite like a war. Indeed, to consolidate party spirit for the then-upcoming Presidential election, Pat Buchanan evokes the United States’ “victories” in various recent wars in his address to the 1992 Republican National Convention. The US invasion of Grenada in 1983, the US-supported Contra War in Nicaragua in the 1980s, and especially Reagan and Bush winning the Cold War by that decade’s end, all serve for Buchanan as exemplars of America’s — read Republican America’s — excellence and essence.

At the time of Buchanan’s address, those wars had ostensibly been won; but Buchanan warns that America is in the throes of another battle, with even more at stake, because this war is being fought on the nation’s own soil. It is “a cultural war, as critical to the kind of nation we shall be as was the Cold War itself, for this war is for the soul of America” (para. 39), fought on one side by the emergent (and insurgent) culture made up of pro-choicers, supporters of gay marriage, L.A. “mobs” (i.e., people of color), and proponents of “radical feminism” (para. 23); and on the other side by the conservative, essentially white, heteronormative, and cismale dominant culture personified by Buchanan himself.

Flash forward two years, and we see the publication of the first issue of Grant Morrison‘s comic book series The Invisibles (DC Comics, 1994-2000), a series which, on its surface, is about the struggles of a band of freedom fighters (the Invisibles) versus the forces that would enslave all of humanity, namely the Outer Church, led by Sir Miles. But The Invisibles is also about the very culture wars that terrified Buchanan in 1992.

The Invisibles are made up those very folks who haunt Buchanan, including King Mob, who has grown from his working-class roots to become an anarchist and master assassin; Boy, a black woman who left her job as a New York City cop once she realized how her role buttressed the structures of oppression; and Lord Fanny, a trans woman born in Brazil whose training as a shaman includes being a sex worker and taking a lot of recreational drugs. And while their weapons include not only standards like guns and knives, but also psychic powers, magic spells, and alien languages, some of their most effective weapons to fight against Sir Miles and the Outer Church are the popular culture — and the nascent subcultures — that so terrify hegemons of conservative culture like Buchanan.

(Vertigo / DC Comics)

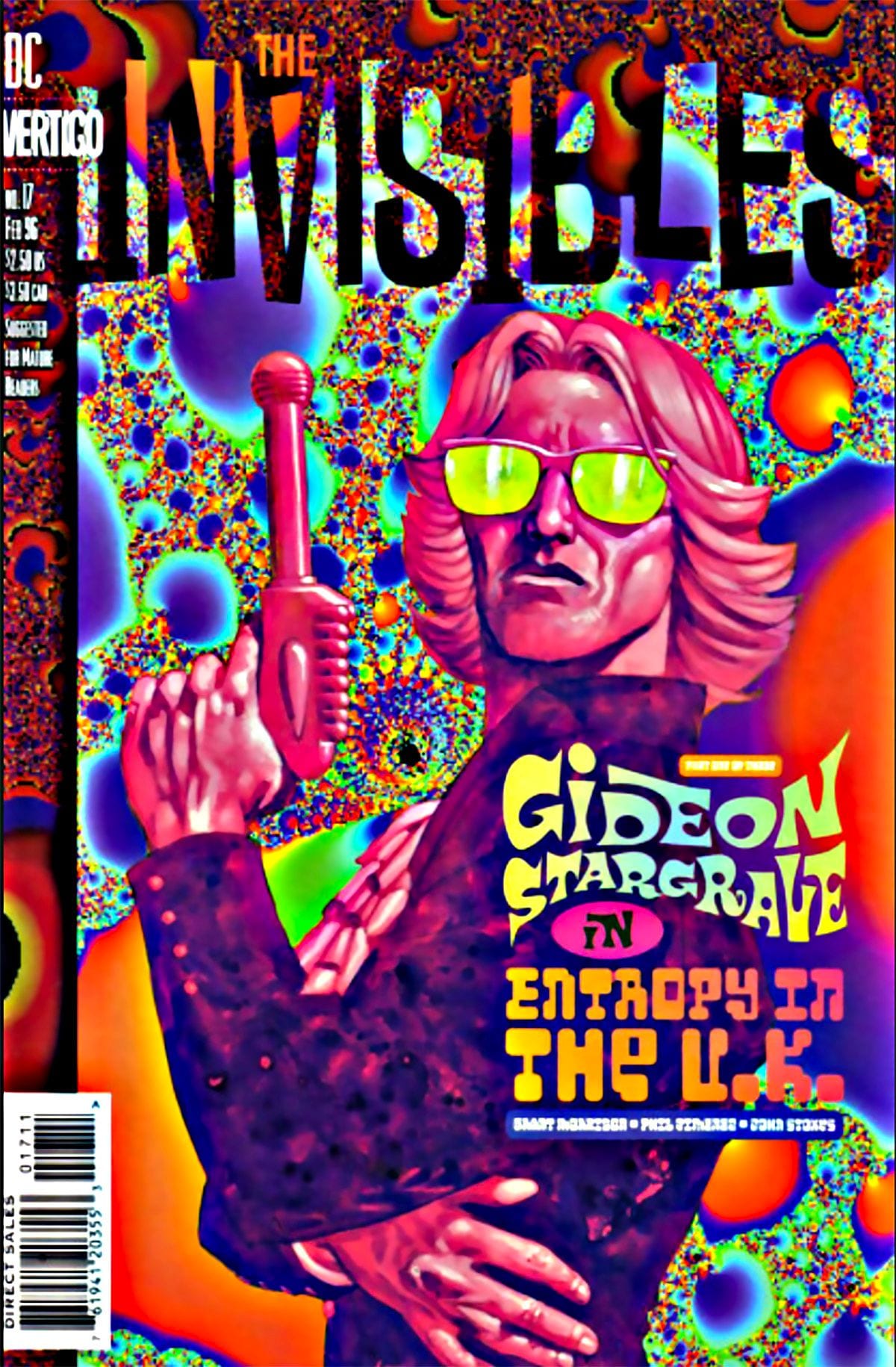

For example, consider The Invisibles # 17, “Entropy in the U.K., Part One: Dandy” (1996). King Mob, having been shot by Outer Church agent Commander Brodie, is in Sir Miles’s clutches. Bleeding and bound, King Mob writhes under Sir Miles’ psychic assault, as Miles invades his mind to discover the secret identities of the other Invisibles. In defense, King Mob lures Sir Miles into fictions, outlandish false “memories” featuring King Mob’s fantasy persona, Gideon Stargrave. In one of these screen memories, we see Stargrave, having just successfully haggled over a used Stealth bomber, flying off to raze Washington D.C. Jarringly, Morrison lists here the “[m]usic on Stargrave’s earplug-sized tape player: The Beatles, The Move, The Shop Assistants, The Mixers, The Jesus and Mary Chain, The Times, The Television Personalities, The Pastels, The Sex Pistols, The 5, Buzzcocks, The Byrds” even as “the bomber sidles up on Washington D.C. The Pentagon is burning, the streets are choked with rioters and dead National Guardsmen. Stargrave releases the bomb with a vague sense of déjà vu“.

This linking of band names with bombs isn’t simply another of those weird, seemingly random juxtapositions that are Morrison’s trademark. Rather, Morrison links popular culture and subcultures with the Stealth bomber here in order to show how they, too, are dangerous weapons, capable of toppling the cultural status quo. Many of the bands on Stargrave’s playlist are those listened to by 1960s and ’70s British Punks and Mods. Elsewhere in the same issue, Morrison itemizes Gideon Stargraves’s clothes: “mirrored Ray-Ban shades, a purple crushed velvet frock coat with matching bellbottom trousers, a lemon frilled shirt from Mr. Fish, paisley underpants from Marks & Spencer and high-heeled Chelsea boots from Shelly’s Shoes!”. Stargrave is a Mod indeed, one of those unsavory youths who, 20 years before Buchanan’s address, were themselves deemed threatening to a nation. As Stanley Cohen writes in Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers (Routledge, 1972), Mods were a scapegoat for Britain’s woes:

One of the most recurrent types of moral panic in Britain since the war has been associated with the emergence of various forms of youth culture (originally almost exclusively working class, but often recently middle class or student based) whose behaviour is deviant or delinquent. […] The Teddy Boys, the Mods and Rockers, the Hells Angels, the skinheads and the hippies have all been phenomena of this kind. (1-2)

By depicting Stargrave as a ’60s/’70s Mod who wreaks destruction on the centers of culture, Morrison obliquely activates the fears of the United States in the ’90s. Temporally displaced a couple of decades, and geographically displaced across the Atlantic, the Mod Stargrave en route to bomb Washington, D.C., stands in for those mobs, queers, and feminists who are causing Buchanan’s own moral panic. Morrison portrays Stargrave and the Invisibles as warriors of the subculture aimed to undermine the figurehead of dominant American culture. The image of Stargrave bombing Washington D.C. represents a subcultural fantasy (and conservative nightmare) of the counterculture destroying the cultural status quo.

Behind such spectacular fantasies, however, The Invisibles demonstrates how real cultural change is effected not through a frontal onslaught but rather through a more subtle infiltration of the dominant culture by those very subcultures that conservatives fear. Near the end of the series, in the issue titled “Satanstorm Three: The ‘It’ Girls” (1999), we find King Mob and Lord Fanny reuniting in London to prepare for the Invisibles’ final battle with Sir Miles and the Outer Church. “Blimey!” King Mob declares. “Britain’s gone mad while we’ve been away.” Fanny concurs: “They have tranny tv presenters here. I feel positively plain.” King Mob then observes how “[t]he world’s getting more like us every day. It’s everything I ever hoped for. Everything is real”.

This invasion of the once marginalized and demonized “trannys” into the mainstream is just what Buchanan exhorted his hearers to beware of as signs that conservatives are losing the culture wars. Indeed, the anxiety of “crossdressers in our midst” is explicitly evoked in Buchanan’s address as a metaphor for the infiltration of liberal political culture, as we see in his description of the recent 1992 Democratic National Convention as “that giant masquerade ball up at Madison Square Garden – where 20,000 liberals and radicals came dressed up as moderates and centrists – in the greatest single exhibition of cross-dressing in American political history” (para. 4). On one level this is typical homophobic snark, but Buchahan’s words also reveal the conservative culture’s real terror that radical elements can penetrate the mainstream, that the mobs, feminists, and gay folks can transform the cultural status quo by attaining — gasp! — acceptance.

Indeed, what Buchanan feared most has somewhat come to pass, as gay folks, at least, have a cultural visibility and influence in 2019 that seemed unimaginable in 1992. The Mod music so feared in the ’60s and ’70s has become part of the cultural mainstream, too. As a depiction of the culture wars of the last decade of the 20th century, The Invisibles presaged that, as they penetrate the mainstream more and more, subcultures that had been marginal are invading cultural territory once thought unassailable. And of course, The Invisibles itself is an example of a cultural form, once deemed insignificant, becoming more and more culturally relevant.

Comic books, too, are counterculture weapons in the culture wars. Even as Morrison has depicted King Mob, Lord Fanny, and the other Invisibles as warriors against the conservative culture that would suppress them, The Invisibles has disseminated their anarchic notions to readers who might, under its influence, fight conservative cultural gatekeepers like Buchanan.

Works Cited

Buchanan, Patrick Joseph. “‘Culture War Speech: Address to the Republican National Convention’ (17 August 1992).” Voices of Democracy: The U.S. Oratory Project. 14 June 2019. Web.

Cohen, Stanley. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and the Rockers. London and New York: Routledge, 2011. Print.

Morrison, Grant. ” Entropy in the U.K., Part One: Dandy.” In The Invisibles: Entropy in the U.K. 6-30. New York: DC Comics, 2001. Print.

–. ” Satanstorm Three: The ‘It’ Girls.” In The Invisibles: The Invisible Kingdom. 55-77. New York: DC Comics, 2002. Print.

- 'The Multiversity: Ultra Comics #1' - Don't Read This Comic ...

- Disinformation: The Complete Series - PopMatters

- If We'd Never Had to Fight a War: "The Multiversity: The Society of ...

- It's Hard to Love the Pieces: "The Multiversity: Pax Americana #1 ...

- Grant Morrison on Action Comics: The PopMatters Exclusive ...

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)