Why would Joan Baez lunge at a spoiled roast beef sandwich on a room service tray in the middle of a hotel hallway? Because that’s how much she worshipped Odetta, who’d taken a bite of that sandwich. Stories about the true legends of Americana can be told in two quick sentences like this. In a lot of cases, their legendary status has been lost in the wash of time, with the whole lives of pioneering musical artists boiled down to two quick sentences. Odetta’s story is arguably one of these: She’s the Queen of American Folk; she spent her whole career in service to the civil rights movement, but even though her music and activism influenced many, she doesn’t always get the level of recognition she so richly deserves.

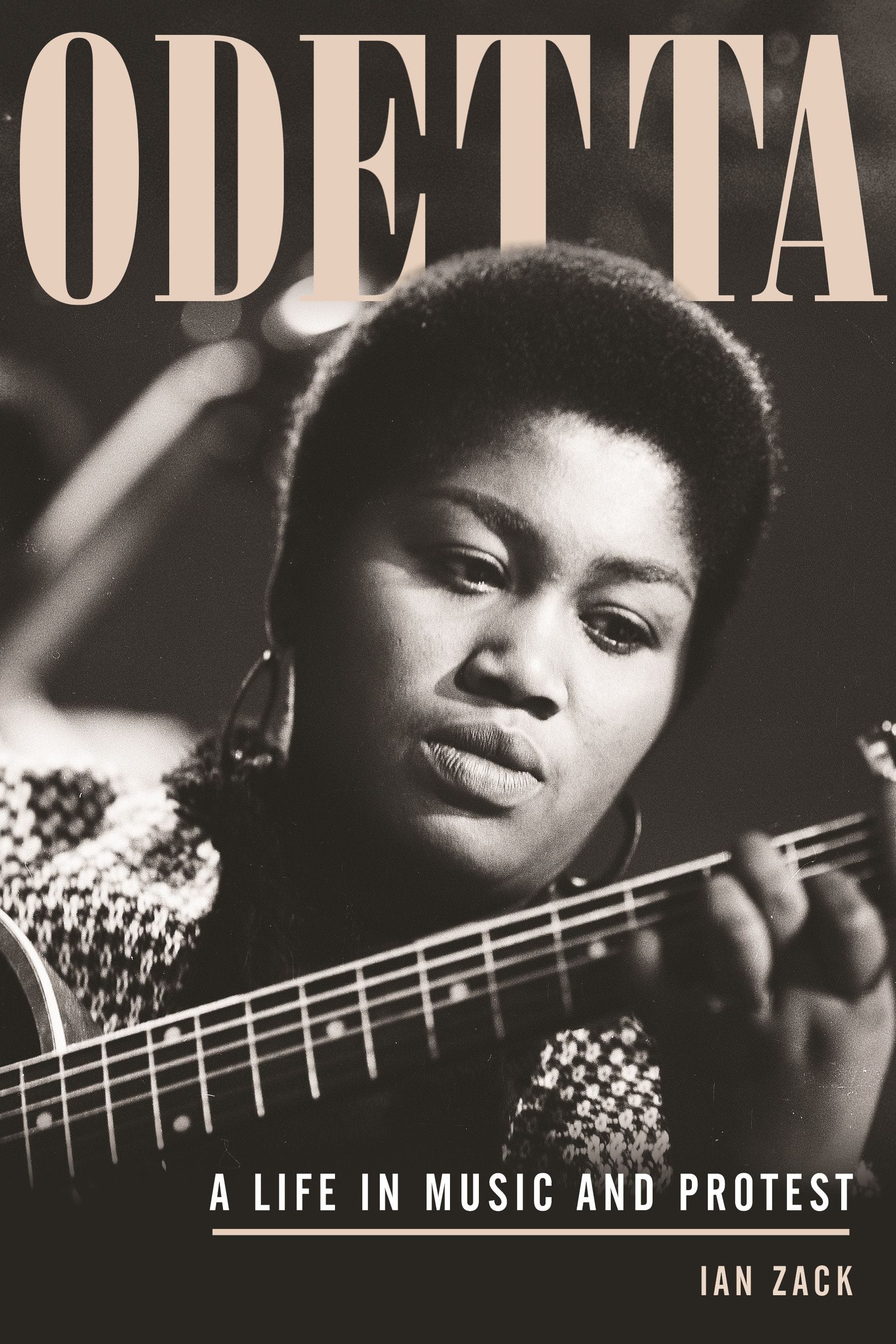

This begs the question: recognition by whom? There are three books about Odetta: one is 2019’s 33 1/3 series book about her One Grain of Sand album written by a professor of African American Studies at Yale, Matthew Frye Jacobson; one is a 40-page children’s picture book, Odetta: The Queen of Folk (2010), by illustrator Stephen Alcorn, who has drawn for a dozen such books on African American historical figures; the last one is Ian Zack‘s new biography, Odetta: A Life in Music and Protest.

Zack used to do the booking for The Good Coffee House, one of New York’s oldest folk venues. His first book was about a similarly unsung musical giant, Say No to the Devil: The Life and Musical Genius of Rev. Gary Davis (read excerpt here on PopMatters.) A fundamental premise of the Odetta biography is that she should’ve been more successful during her lifetime and more enduringly known after she passed away in 2008. Zack delves deeply into her life and work, but his mixed results only seem to highlight an unexamined divide between black and white folk audiences.

Throughout her lifetime, the majority of Odetta’s audience was white, which further begs the question of who remembers her now. Zack’s book is about race relations and the social justice mission that fueled Odetta’s personal rage and professional shows with unabating consistency for decades. Yet the author doesn’t much attempt to use these same politics of identity as a lens through which we can examine Odetta’s supposedly undervalued legacy. He makes clear that she could’ve had better management, and even that Odetta accused later managers of giving her short shrift due to ongoing industry racism. Zack provides counter testimonials from other acts with the same managers or people orbiting their scene, indicating that Odetta’s managers were not so much racist as money-grubbing. Why not tie the idea of Odetta’s weaker financial bottom line to the fact that the market became much less interested in black folk performances once Peter, Paul and Mary arrived on the scene?

Or Joan Baez. The roast beef sandwich story makes clear which way the winds of inspiration blow, right? Yet many interviewers who hadn’t done their homework would ask Odetta if she was inspired to sing folk music because of Baez—to which Odetta replied with righteous indignation, “I’m the mama and they’re the children, and I influenced those singers” (199). Odetta launched Joan Baez. She motivated Maya Angelou. She is before Aretha. She is before Mavis. She is so much before the Newport Folk Festival that it was one of her managers who launched that festival. Odetta is before Bob Dylan, electric or acoustic. She is the one who inspired him to try doing folk music and eventually released an album of Dylan covers that cemented his place in the folk pantheon.

Singing Birds by Dieter_G (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

It’s an inspiring story that shouldn’t end up on the cutting room floor, as did so many of the guest roles she played in films during her lifetime. Odetta sang and played guitar. She could act, and she was also an activist. Rosa Parks was a big fan of her music, and it seems as though that same sound has a lot to offer us in these weird times. On the value of music itself as activism, Odetta once rather defensively mused, “I could run around like a chicken with its head cut off, but you have to choose. Many times it is felt you’re not accomplishing anything unless you get your head knocked” (167). Odetta was there to sing at Selma in 1965 when John Lewis got his head knocked for marching for civil rights. She was there to sing at the March on Washington before Dr. Martin Luther King’s historic 1963 speech. There was a long stretch in the ’50s when she was the number one phone call for anything Harry Belafonte wanted to do, including that first television music show featuring an integrated cast of performers. Odetta is before Belafonte.

To a large extent, all of these examples are about putting a dent in the obliviousness of white culture. Zack paints a portrait of a singer devoted to telling the black stories that allowed white audiences to exercise empathy, to confront historical injustices, to convert to the cause of equality for all. She was the first black performer to get gigs at many white night clubs, and for a long while, she made big money.

Zack clearly shows that she was a pioneer, not a novelty act. One of the delights of his characterization is how regularly he will acknowledge that she was unreasonable, or that she acted rather selfishly. She had a rage inside of her big-boned, dark-skinned body that provided an endless source of performance energy. It’s not unlike what you can see radiating off Queen Latifah in her portrayal of Bessie Smith in the 2015 HBO film Bessie. As a matter of fact, Odetta was dying to play Bessie and repeatedly tried to get such a movie made.

She didn’t live to see Latifah play the part, but she did live just long enough to see Barack Obama get elected president. In her final days at the end of 2008, she’d been planning to sing at the inauguration that was, in many ways, a fitting capstone for her life’s work.

Nearly everything she did was about putting black stories in front of white audiences, but how did she fare with black audiences at the time? Zack also points out that Odetta did a lifetime’s worth of tiny gigs to help out local schools, church groups, or whoever had a fundraiser going that week. Those shows are naturally not as well documented or preserved as the night club gigs, but she was an extremely reliable invite for benefit shows of all kinds. It goes unsaid by the author, but there seems to have been no money for Odetta in performing for black audiences despite the retrospective clarity that she is a hero of the civil rights movement.

Even at the time, Zack says that Odetta’s efforts to reach beyond folk music, to perform and record blues music, were repeatedly rejected by live audiences and industry players alike, until near the end of her life when she was finally nominated for a Grammy for the 1999 album, Blues Everywhere I Go. She was said not to have been as soulful a singer as Aretha Franklin. The folk/blues distinction is often not predicated on particularly objective musical standards; there’s an undercurrent of criticism throughout Odetta’s life that she was perhaps simultaneously “too black” and also “not black enough”, which Zack would’ve done well to analyze more explicitly for setting the historical record straight.

My favorite chapter in Odetta appeared very early on, and it’s the one place where Zack does make very clear how a black audience received Odetta. It’s true her music launched a thousand musicians, that Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie were her biggest fans, and that there would never have been a folk music scene without her. But the specter of her physicality was more instantly the stuff of legend. I was very interested to learn about how Odetta caused a resurgent proliferation of the afro in America. She quit straightening her hair and cut most of it off in the summer of 1952, when she was just 22-years-old. No reasonable African American striving to become a successful entertainer would have done that, but she did.

Because of her large physical size, her managers did not want to put her entire body on an album cover. It was intimidating to look at her flat image in a photo without the accompanying warmth of her actual performance. So they used headshots, thus highlighting her natural hair at a time when black women and men were yielding to social pressures to make their naturally curly hair straight — many relied on scalp-burning lye to achieve the look. That she decided to face the world with her natural hair was a revolutionary “black is beautiful” message long before James Brown came along with”Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud”. Throughout the book, Zack also emphasizes how Odetta would wear African fabrics on stage, but there’s not much discussion of how this was received by either black or white audiences.

Odetta tells a great story, and while the particulars may be fresh, the arch of its plot is decidedly familiar: a youth full of hardship, the inspiration to get on stage and sing, some moments of skyrocketing success, an eventual return to hardship and ultimately a rather quiet fading away. Zack is a good storyteller, impeccably integrating research to tell most of the tale himself, but gently sprinkling in some quotations from interviews with those who knew her best to get the fullest emotional effect. Odetta’s grade school friend Jo Mapes recalls, “I was pimply, fat, shy, and white. She was pimply, fat, shy, and black. We hit it off immediately” (8). The interviews yield not only the tears involved in a life full of troubles and few hard-won recognitions, but also humor, as when Odetta was finally given the key to the city of Birmingham where she grew up, and she remarked, “for a big city, that’s a little key. Don’t guess it opens anything” (175).

It’s stunning to think of the prices she most certainly paid for expressing her reality so clearly. In reading Zack’s biography, I often wished he’d been equally direct in his judgment of how much of her legacy is blunted by considerations of race both now and while that legacy was in the making. Perhaps he was striving to preserve the voice of a biographer, and indeed, it’s good that we now have one proper biography of Odetta. But I find myself longing for a cultural critic or more daring historian to pick up where this book’s mission ends, to fill in some analysis of the historical gap between black and white folk audiences. Integrating white-dominated folk was no doubt a major hurdle, and it’s more or less implied in Zack’s biography. But he chooses to let it lie in the periphery.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)