Muscle Shoals Sound Studios, 1976. Kim Carnes is recording Sailin’ (1976), her second album for A&M Records. Jerry Wexler, her dream producer, presides from behind the console. Session vocalists Julia Waters and Maxine Waters have flown in from Los Angeles to join Carnes on background vocals. The three have sung together on countless sessions, but this time something special happens when they harmonize on the title track. Singing a cappella, the seamless blend of their voices stops time. Only hours later, Carnes will have recorded all of her lead and background vocals for the entire album.

“I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed greater rapport with a singer,” Wexler later wrote in his autobiography Rhythm and the Blues: A Life in American Music (1993). “With Kim in the studio and me in the booth, the good feelings flowed back and forth almost mystically. A nod of my head and she understood what I was saying, where I was pointing her. She’s a fine musician, her sultry voice a marvelous instrument.” The legendary producer of icons like Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Dusty Springfield, and Bob Dylan simply stated what other esteemed producers, artists, musicians, and songwriters have known for years: Kim Carnes is exceptional.

“Sailin'” depicts the wanderlust of a seafaring dreamer. In a way, Carnes’ musical compass has navigated different currents throughout her career. Muscle Shoals is but one stop on a creative exploration marked by SoCal pop-rock, Nashville-based roots music, and detours to London’s New Romantic scene. Big Mama Thornton, Frank Sinatra, Tina Turner, Tim McGraw, and even the cast of Glee, are among Carnes’ fellow travelers who’ve each contoured her lyrics and melodies with their unique interpretations. Her self-penned duets with Kenny Rogers and Barbra Streisand have steered her songwriting to new vistas of creativity and imagination.

During the summer of 1981, however, Carnes reached a career milestone. Her recording of Donna Weiss and Jackie DeShannon’s “Bette Davis Eyes” crowned the Hot 100 for nine weeks while Mistaken Identity (1981) spent four weeks at number one on the Billboard 200. The New York Times declared “Bette Davis Eyes” the “pop-single phenomenon of the year” (26 July 1981) as the song soared to number one in more than two dozen countries around the world, and later won “Record of the Year” and “Song of the Year” at the Grammy Awards. Bette Davis herself forged a friendship with Carnes and quipped to People Magazine, “Not being a Rita Hayworth or a Jean Harlow, my eyes were probably my biggest asset” (6 July 1981).

“Bette Davis Eyes” is one of those rare recordings that both defines and transcends its time. Yet, the true measure of Carnes’ impressive longevity is a rich, vast body of work that underscores why music industry mavens have constantly sought her talent. In this exclusive interview with PopMatters, Carnes retraces the arc of a fascinating career that’s still flourishing. A few of her longtime collaborators join the conversation, while more than a dozen singers, songwriters, and musicians, from Melissa Etheridge to Giorgio Moroder, honor Carnes in a special postscript that illuminates the scope of her musical legacy.

“Distinctive In Her Own Right”

AM radio reflected a revolution in music during the mid-’60s. The confluence of Motown and the British Invasion on the airwaves captivated teenage listeners. Growing up in Pasadena, California, Carnes had been singing and writing songs since she was three-years-old, but it was the radio dial that stoked her musical passion. She recalls, “My greatest influences were Smokey Robinson & the Miracles — Smokey above anybody — the Rolling Stones, anything Motown. Right after that, Bob Dylan was a huge influence when I started paying attention to what he was doing.”

Delaney & Bonnie records signaled a turning point for Carnes. “All of my heroes were always dudes, but when I heard Bonnie Bramlett sing, it changed everything,” she says. “I went, ‘A girl can sing like that‘? She was a tremendous influence. I don’t think she has any idea how much of an influence she was on me. I thought, That’s how I want to sing. That’s soulful!”

Meanwhile, an October 1970 Billboard item stated that Amos Records founder Jimmy Bowen had launched a publishing division for his production company. As a former staff producer for Reprise Records, Bowen had secured a record deal for the First Edition and counted gold-selling number one smashes for Frank Sinatra (“Strangers in the Night”), Dean Martin (“Everybody Loves Somebody”), and Sinatra’s duet with daughter Nancy Sinatra (“Somethin’ Stupid”), among his many hit productions. Earlier that year, Bowen had also begun expanding his label’s roster through a new distribution deal with Bell Records.

Mike Settle was among Bowen’s new signings. An original member of the First Edition, he’d met Carnes, her husband Dave Ellingson, and First Edition frontman Kenny Rogers years earlier during their tenure in the New Christy Minstrels. “I played Mike some songs I’d written,” Carnes recalls. “He said, ‘You know what? I’m with Jimmy Bowen. He needs to hear you.’ We went to Jimmy’s and I played him a couple of songs on the piano. ‘I Won’t Call You Back’ was the first song I played for him. Bowen said, ‘I like what you’re doing. Why don’t you come up for dinner next week? I’m having a bunch of people. You can play me more songs.’

“We go up to dinner and the room is filled with songwriters and singers. We have this great dinner where weed is sprinkled on everything we ate! It’s about two in the morning. Everyone’s gone except for me, Dave, and Mike Settle. Bowen said, ‘Okay, now that we got the place to ourselves, sit down and play me some more stuff.’ I sat down, I looked at my hands on the piano, and went [pauses] ‘I can’t … I can’t play. I’m too stoned to play!’ He laughed so hard. He said, ‘Don’t worry about it. I love what you do.’ That is a moment I will never forget: I’m playing for somebody I want to be my first publisher and I’m too stoned to play the piano. Of course, Jimmy thought it was hysterical.”

A bright constellation of singer-songwriters orbited Bowen’s world. J.D. Souther and Glenn Frey, who recorded as Longbranch/Pennywhistle, released their eponymous debut on Amos in 1969. Two years later, Kenny Rogers produced Shiloh (1971) for Bowen’s label. The group featured Frey’s future bandmate, Don Henley. “Bowen has this wonderful sense that can’t be taught — spotting who he thought was going to do well,” says Carnes. “If you look at who was with his publishing company, every single person went on to not just be successful, but have huge success. He knew the difference.”

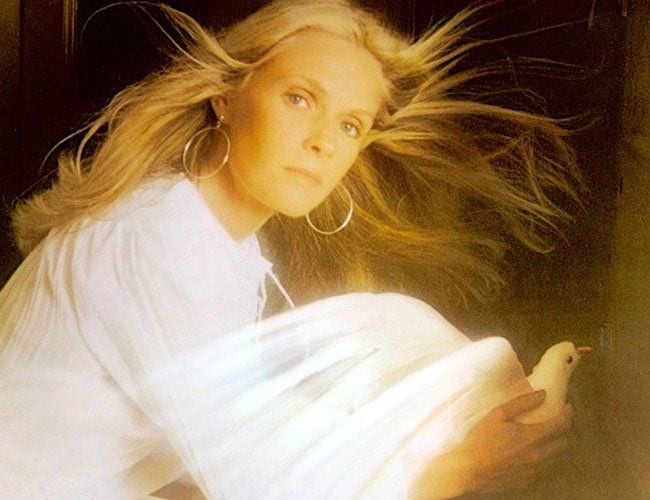

Sailin, 1976 (courtesy of A&M Records)

Carnes’ first glimmer of international success arrived by way of Vanishing Point (1971), a road film starring Barry Newman, Cleavon Little, Dean Jagger, John Amos, and (in the UK version) Charlotte Rampling. In fact, no less an auteur than Steven Spielberg would later cite Vanishing Point as one of his favorite films. Bowen produced the soundtrack, which included a tune by Delaney & Bonnie, and enlisted his roster of talent to write and record additional songs for the film.

After viewing a rough cut of Vanishing Point, Carnes penned “Sing Out for Jesus”. She says, “I don’t know where that song came from. I am not a religious person. When I play it for friends who know me now, they look at me and go, Huh?.” However, “Sing Out for Jesus” was destined for greatness when Big Mama Thornton cut it for the soundtrack and became the very first artist to record one of Carnes’ songs. “To have Big Mama Thornton sing my first cut? It just doesn’t get any better than that,” says Carnes, who has a vivid memory of the recording session:

“When she came in to do her vocal, she had her quote ‘boys’ with her. She started to sing it and it just wasn’t working. I’m thinking, This is Big Mama Thornton and this is my first cut. It has to work! Her boys came over to Bowen and said, ‘We’re going to take Big Mama out. We’ll be back soon.’ I thought, Are they ever coming back? [laughs]

“They came back in about half an hour. One of her boys carried a paper sack into the studio. She got in front of the mic and took the top off the bottle that was in the paper sack, which ended up being Old Grand Dad. She went gulp gulp gulp gulp … ahh!. She put the sack down and did the vocal. She just needed a little inspiration. She back-phrased so far. I was on the edge of my seat in the booth going, Is she going to make it to the end of the phrase? That was her great ability — to make it perfectly. Nobody else could do that. I was floored and thrilled. I’m still so proud that that was my first cut as a writer.”

Richard Sarafian’s Vanishing Point (1971) also brought the voice of Kim Carnes to movie-going audiences as a song called “Nobody Knows” played over the closing credits. Written by Mike Settle, it spotlighted a guttural, blues-infused performance from Carnes. “I had no idea how I was going to sing ‘Nobody Knows’ until I got in front of the mic,” she says. “This vocal came out. Everybody said, ‘Where did that come from?’ I just said, ‘I don’t know. I’m as surprised as anybody.'” Bowen prepared “Nobody Knows” for single release on Amos, crediting Carnes and her husband as “Kim & Dave” on the label.

A week before Vanishing Point opened, Billboard highlighted “Nobody Knows” in its “Special Merit” column, citing the duo’s “top performance” (6 March 1971). Despite industry acclaim, the single missed the charts altogether. “I was so proud of that record, but it wasn’t a hit,” says Carnes. “There was so much praise of it that I just expected it to go flying up the charts. I thought, All I’ve got to do is make a record. It will be a big hit and I’ll be off and running. I learned a hard lesson quickly — don’t believe the hype. Don’t ever take anything for granted that it’s going to work.”

Nevertheless, Carnes closed 1971 with an important benchmark, the release of her full-length solo debut, Rest on Me (1971). The album showed the singer’s facility with a range of material, including hits by Anne Murray (“It Takes Time”) and the Bee Gees (“To Love Somebody”), as well as Bobby Freeman’s “Do You Wanna Dance” and Gerry Goffin-Carole King’s “To Love”. Carnes also lent nuanced performances to “Sweet Love Song to My Soul” and “One More River to Cross”, a pair of tunes written by Daniel Moore, who’d known Ellingson since their days in the Fairmount Singers.

Both of Carnes’ own songwriting efforts for the album, “I Won’t Call You Back” and “Fell In Love With a Poet”, furnished evocative showcases for her voice. “These nights alone just make my heartache grow,” she cried on the former, sketching the lyrics with anguish. She evoked a more wistful mood on the latter tune. “I was really finding my voice,” she says. “I was trying out different vocal styles. That’s why ‘Fell In Love With a Poet’ and ‘I Won’t Call You Back’ are the same person, but they’re different.”

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

Track for track, Jimmy Bowen inspired Carnes to give her all, surrounding her with top studio musicians and orchestrating the songs with strings and horns. “Bowen’s very perceptive and extremely smart,” she says. “As a producer, he’s the artist’s best friend. He’d always say, ‘My job is to figure out who the real you is and get that out of you — your best songs, your best performances.’ I loved working with him.”

Industry trades championed Rest on Me upon its release in December 1971. “A fabulous album,” Cashbox declared in its review. Billboard viewed Rest on Me through the lens of singer-songwriters like Carole King and Carly Simon, calling Carnes “distinctive in her own right” (11 December 1971). Indeed, Amos Records had delivered an album packed with potential smashes.

Rest On Me may not have yielded any hits, especially since Amos was close to shuttering at the time of the album’s release, but it established Carnes as an important presence in LA’s fervent music scene. “Hollywood, in the ’70s, was the mecca for songwriters,” she says. “If you were a writer or a publisher, you all eventually knew each other and hung out at the same places. We all shared demo time and sang on each other’s songs. The spirit was everybody rooting for everybody else.

“We would go to an Italian dive in Hollywood called Martoni’s. Everybody would go there, drink wine, and just talk about what we were doing and what we were writing. I remember going there after a session. Bowen said, ‘Kim, just keep doing what you’re doing. Keep getting cuts as a songwriter. Do what you love. It will happen someday, but it could take much longer than you’re expecting.’ He was exactly right.”

Over the next few years, Carnes’ songwriting career flourished as marquee acts began recording her songs on major labels. Kenny Rogers & the First Edition cut “Where Does Rosie Go” on Transition (1971). Nancy Sinatra’s Woman (1972) album featured her rendition of “Fell In Love With a Poet” and “It’s the Love That Keeps It All Together”, a tune that Carnes and Ellingson had previously recorded for Amos. Riding the wave of teen stardom, David Cassidy cut “Song for a Rainy Day” on Rock Me Baby (1972) and collaborated with Carnes and Ellingson for two songs on Dreams Are Nuthin’ More Than Wishes (1973), which topped the UK chart. One of Carnes’ most prestigious gigs duly followed: co-writing “You Turned My World Around” for Frank Sinatra on his nod to contemporary songwriters, Some Nice Things I’ve Missed (1974).

“She Was Just Being ‘Kim Carnes'”

Parallel to her songwriting career, Carnes had also begun doing background work with some of LA’s top record producers. “I love singing harmony vocals,” she says. “Anybody who asks me, I am there. I love it, especially with Julia and Maxine.” The Oscar-winning documentary 20 Feet from Stardom (2013) emphasized just how integral Julia Waters and Maxine Waters, and their brothers Luther Waters and Oren Waters, have been to the world of background singing. In the mid-’70s, Carnes became an honorary Waters sister.

Steve Cropper was the force that brought Carnes and the Waters together. At the time, he was co-producing José Feliciano’s For My Love… Mother Music (1974) album. “He said, ‘I know all of your voices and I just have a feeling that you’re the third sister,'” Carnes recalls. “Sure enough, Maxine was low, I was in the middle, and Julia was the high part. From the first time we sang, we looked at each other and said, ‘It’s like we’ve been singing together our whole lives!’ It’s something you can’t learn. It’s either there or not there.”

Julia Waters adds, “Kim’s voice just blended in so perfectly with ours. I loved her voice because she was such a raw talent. She wasn’t trying to be a ‘soulful white girl’. She was just being Kim Carnes and we were just being who we were. And it worked.” Indeed, the blend that Carnes shared with the Waters would grace several projects, including Tina Turner’s Acid Queen (1975), and albums by everyone from Andy Williams to future Oingo Boingo member Carl Graves.

In the meantime, music publishing powerhouse Chappell Music offered songwriter Eddie Reeves (“All I Ever Need Is You”) a position as vice president of the company’s west coast division. Carnes and Ellingson were the first songwriters that Reeves signed upon the beginning of his tenure in 1974. Almost immediately, Phil Spector offered Carnes a recording contract with Warner-Spector after hearing a demo of a brand new song she’d written,”You’re a Part of Me”. Carnes recalls, “He loved that song. When we went to his house in the Hollywood Hills, he played it about 20 times while we were there. He kept playing it over and over again.”

However, there was only one place where Kim Carnes wanted to be — A&M Records. “In those days, they were the ‘singer-songwriter’ label,” she says. “I loved the artists they had. I loved that they were on an old movie lot. I loved their whole philosophy, which came down from Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert. They treated their artists with such respect. I knew it was the only label I wanted to be on.”

Carnes approached A&M staff producer David Anderle, who also helmed A&R for the label. “We played ‘You’re a Part of Me’ for him, I believe, for Rita Coolidge,” she recalls. “It’s the song that really started the journey of me begging A&M to sign me. That started the dialogue and my friendship with David. He loved it and was a huge fan of my songs. I waited for so long to be on A&M. They kept saying, ‘We have our girl singer. We can’t sign you.'” Industry quotas notwithstanding, Anderle continued to champion Carnes until A&M executives, at long last, offered her a recording contract.

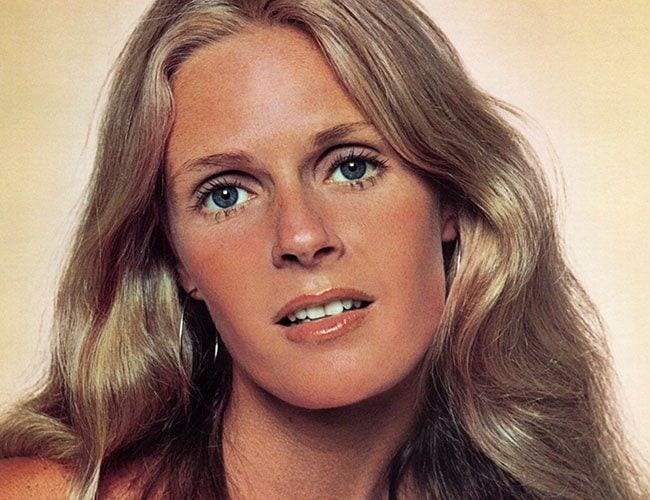

AM, Kim Carnes, 1975 (courtesy of A&M Records)

Kim Carnes is exactly what listeners got on Kim Carnes (1975). Whereas Rest on Me had featured other writers’ material on all but two songs, Carnes’ A&M debut flipped the ratio and proved how well her own songs translated to the studio. She also settled into a more consistent vocal style. “Because I’d been doing so many demos and writing so much, I knew much more of who I was,” she says. “Vocally, the album wasn’t all over the place. It’s much more, even.”

Mentor Williams, who’d penned and produced Dobie Gray’s “Drift Away” two years earlier, led a team of venerable studio players that included Jim Keltner (drums), Leland Sklar (bass), Dean Parks (guitar), Michael Utley (organ), and David Foster (piano). “They were wonderful musicians, wonderful human beings,” Carnes says. “I really aligned with David. He was the new kid in town from Canada. He ‘got’ me and understood that I should be doing my songs.”

Julia Waters and Maxine Waters also joined their “third sister” in the studio for her second solo outing. Their vocal blend embellished the gospel feel of “Nothing Makes Me Feel as Good as a Love Song” to scintillating effect and added a dash of zeal to more sprightly tunes like “Bad Seed”, “It Could Have Been Better”, and “Hang On to Your Airplane (Honeymoon)”. Ellingson and Williams even joined the vocalists in the closing moments of “Do You Love Her”, a heart-wrenching tune where Carnes realizes “Sometimes the love that burns the brightest, burns itself right out with time”. David Briggs’ beautifully orchestrated strings glistened like freshly fallen tears.

“And Still Be Loving You” paired words and music together perfectly, with each chord progression mirroring the sentiment of each lyric. “Kim’s writing is phenomenal,” says Julia Waters. “It’s like her — it’s for real. She puts her whole self into it.” Carnes adds, “I’m so proud of ‘And Still Be Loving You’. It’s filled with melancholy. I always thought it would be a great movie song. I love it.”

Released in November 1975, Kim Carnes earned rave reviews beyond the trade magazines. “She writes songs that touch on various shades of romance in a warm, gently appealing way that outclasses virtually everything in today’s easy listening sweepstakes,” wrote the Los Angeles Times. In his review for Rolling Stone, future New York Times critic Stephen Holden also applauded the singer’s maiden A&M release, stating “Kim Carnes is definitely a talent to watch” (1 January 1976).

“You’re a Part of Me” — the song that started it all — gave Carnes her first solo hit when it peaked at #32 on Billboard‘s Adult Contemporary chart the week ending 14 February 1976. Its shelf life had only just begun. It would become one of the singer’s most covered songs, from Anne Murray’s recording on Let’s Keep It That Way (1978) to Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash’s performance on The Johnny Cash Christmas Special (1978). Even Carnes herself would score her first Top 40 pop hit when Gene Cotton invited her to record “You’re a Part of Me” as a duet on his Save the Dancer (1978) album.

For her second A&M release, Carnes flew to Muscle Shoals Sound Studios in Sheffield, Alabama and recorded one of the finest albums of her career, Sailin’. “I remember Kip Cohen, who’s the head of A&R said, ‘Who would you like to produce this album?’ I said, ‘This is really a reach, but my idol as a producer is Jerry Wexler.’ He said, ‘Well, let’s see.’ The next day he called and said, ‘Jerry Wexler loves what you do. He would be thrilled to produce you.’ I couldn’t believe it! I was just so happy. I started writing songs. We corresponded daily. He was amazing, as far as constantly being involved until we felt we had all of the songs.”

This time around, members of the famed Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section accompanied Carnes in the studio, along with Wexler, co-producer Barry Beckett, and the Waters sisters. The caliber of musicianship shrouded each song in excellence, beginning with album opener “The Best of You (Has Got the Best of Me)”. Layers of strings gradually unfolded around acoustic guitar and bass while Carnes gently caressed the song’s melody. Pete Carr answered her on electric guitar as she sparked the chorus with a husky vocal.

The singer accompanied herself on piano for “He’ll Come Home”, narrating a story about a woman convinced that her roving lover will someday return. The song’s brilliance was in the quotidian details that Carnes created for the character, how she writes him unsent letters, masks her feelings with makeup, and numbs the pain with too many sips of wine. On an album defined by greatness, Rolling Stone would later select “He’ll Come Home” as the singer’s best vocal performance on Sailin’.

Barbra Streisand and Kim Carnes 1984 (courtesy of Columbia Records)

Whether covering Van Morrison (“Warm Love”) and Gerry Goffin (“It’s Not the Spotlight”) or setting sail with rousing originals like, “Last Thing You Ever Wanted to Do”, Kim Carnes was undeniably in her element at Muscle Shoals. “I started doing my lead vocals,” she says. “It was going so well that Wexler said, ‘Do you want to keep going?’ It was getting later and later. I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘I’ve never done this with any other artist, not Aretha or anybody.’ I kept going and I did all the backgrounds and all the lead vocals in that one afternoon and night.”

Carnes drew from the depths of her soul to render the heart-stopping melody of “Love Comes from Unexpected Places”. Master keyboardist Bill Cuomo helped arrange the song and played piano underneath’s the singer’s exquisite vocal. “Bill was my right and left hand,” she says. “I could write a song on keyboard and he would watch the way I played it, not just the notes, but the feel and the inversions. Compassion and empathy came through his fingers to the keyboard.”

Cuomo had met Carnes earlier in the decade when they began recording piano-vocal demos for songwriters. “Gloria Sklerov was one of the writers that we worked for a lot,” he recalls. “She told me that every song that Kim and I did for her got cut.” He’d since become close friends with Carnes and Ellingson. “I fell head over heels for Kim,” he continues. “I thought, She’s a really nice person, a fantastic singer, easy on the eyes. I met her husband Dave and I fell equally for him — he’s just the greatest guy in the world.” The gripping combination of Carnes and Cuomo’s talents on “Love Comes from Unexpected Places” signaled a creative partnership that would only strengthen over the next decade.

“Sailin'” was the lustrous centerpiece of the album, a passport to tranquil seascapes and sunlit horizons. “I love the ocean, more than anything else,” says Carnes, who wrote the song on piano. “I can just live on the ocean forever.” The essence of the lyrics was tangible in the music. “It felt like what the song was about,” says Maxine Waters. “The melody of that and the smoothness of it … the song did what it said.”

David Grisman’s mandolin solo complemented the song’s breezy sway, as Carnes and the Waters sang harmonies that stirred the soul. “In that song, we had an a cappella part that the three of us did,” says Julia Waters. “It took you to la la land! It was so beautiful.” Cuomo concurs, adding “The way they sang together was astounding. I loved it.” For Carnes, harmonizing with the Waters on “Sailin'” was more than just a highpoint on the album. “I loved being part of Maxine and Julia,” she says. “Those are some of the best days of my whole career. When I started doing my own tours, the three of us would start ‘Sailin” a cappella. We haven’t done that together for a long time. I just dream of starting a show with the three of us singing that song. It’s way overdue.”

Once again, Carnes won applause from critics. “Sailin’ is a solid album by a promising singer/songwriter,” Rolling Stone stated in its review (7 April 1977). Billboard was even more effusive, noting “Carnes’ second album demonstrates further a remarkable singing and songwriting talent. Support by Muscle Shoals Horns and some fine backup musicians makes this an outstanding effort” (22 January 1977).

“Love Comes from Unexpected Places” emerged as the album’s most lauded composition, winning top prizes for Carnes and Ellingson at the 1976 American Song Festival and the Tokyo Song Festival. Cuomo explains the song’s particular allure. “It breathed,” he says. “You’re kind of hanging on, waiting for the next lyric. It was all from the heart, which made it all the better.” The impact of “Love Comes from Unexpected Places” would extend beyond Carnes’ own spellbinding version. Between 1976 and 1977, Barbra Streisand, José Feliciano, and Táta Vega each recorded their own rendition of the song.

Reflecting on the Sailin’ sessions, Carnes cherishes the memories of working with Jerry Wexler. “I felt like I was recording with Buddha,” she says. “He was funny and loving. He was pure class. He was pure joy. There was an incredible friendship that grew out of our working together.” Wexler himself would later write in his memoir that producing Carnes was “tremendously satisfying”. As Carnes’ next album would illustrate, Buddha taught her well.

“And Now … Kim Carnes!”

In December 1977, Billboard announced a new record company with a familiar name. “EMI America has been officially launched by Capitol Industries-EMI, Inc.,” the magazine wrote (17 December 1977). Kim Carnes had been determined to sign with A&M, and now EMI America’s newly appointed president Jim Mazza was determined to sign Kim Carnes.

“Jim Mazza, who had been Head of Marketing for Capitol International, had heard my A&M albums,” Carnes recalls. “Unbeknownst to me, he was a huge fan. A mutual friend called me and said, ‘My friend Jim Mazza wants you to be the first artist. I said, ‘I can’t. I owe A&M another album.’ He said, ‘Will you at least have dinner with him?’ I said, ‘Well, sure.’ We had dinner. I was ready to sign the table cloth! Can this be the contract? He so totally understood who I was. I didn’t want to leave A&M. I loved A&M. I wasn’t unhappy with them. I just realized that if I signed with this new label, which was new to the US but had all of the EMI funds behind it, I wouldn’t have any competition.

“I went to David Anderle and he said, ‘Let’s have lunch with Jerry Moss and you tell him this.’ I was scared to death! My fate was in the hands of Jerry Moss and he didn’t even hesitate to say, ‘I would never hold you back.’ His exact quote was, ‘Life is too short. How could I say no to you?’ He said, ‘I know your publishing deal with Chappell is about to be up. How about if you sign with A&M publishing (Almo), so you’re still part of our family over here, but I don’t hold you to that third album?’ That’s a phenomenal opportunity so I owe Jerry Moss a lot. He’s such a gentleman. It all worked out great.”

In January 1978, EMI executives chose the industry’s annual MIDEM conference in Cannes to make it official: Kim Carnes was the very first artist signed to EMI America.

EMI granted Carnes and Ellingson complete autonomy in producing St. Vincent’s Court (1979), the singer’s debut for the company. The couple asked their longtime friend Daniel Moore to co-produce the album. “Danny’s an incredible musician and songwriter,” says Carnes. “He’s got so many musical gifts.” Moore brought those gifts to the fore in several capacities, from arranging to producing. “I was very comfortable in the recording studio,” he says. “I’d started producing back in 1965. I was still producing records, but more of my effort was spent on songwriting.” In fact, two of Moore’s writing efforts had scaled the charts in 1973 when B.W. Stevenson made “My Maria” a Top Ten smash and Three Dog Night took “Shambala” to number three on the Hot 100.

Beyond the two songs he contributed to Rest on Me, Moore and had also done background work with Carnes. “I remember doing a session with B.W. Stevenson where the background singers were myself, Linda Ronstadt, and Kim,” he says. “I thought Kim held her own with any of the female singers who were around.”

In reviewing St. Vincent’s Court for Billboard, Kip Kirby wrote, “Kim Carnes is an artist whose voice makes you search for the proper textured imagery in which to convey its rich and special fabric” (17 February 1979). The songs on St. Vincent’s Court evidenced a multitude of textures in Carnes’ voice, from the aching rasp she deployed on “Stay Away” to the silkier tones that threaded through “Jamaica Sunday Morning”. A touch of wonder graced her vocals on “Goodnight Moon” while she retained a beguiling intimacy on “Lose In Love” even as strings swept across the track.

The opening glissando on “Paris Without You (St. Vincent’s Court)” ushered listeners to a vivid fantasy world laced with longing. “I’ve always been able to picture situations and write them in my head first,” says Carnes. “I pictured this girl who’d always wanted to go to Paris with the person she loved and it wasn’t going to happen: ‘I just can’t imagine walking Paris without you.” The song stemmed from Carnes’ deep and abiding affinity for the City of Light, a place that even appeared in recurring dreams. “I used to say I lived in Paris in my past life,” she continues. “I just longed to go back there. ‘Paris Without You’ came, in part, out of my obsession with, I know I used to live in Paris! I’m so proud of that song. I wrote it on keyboard and Bill played it perfectly.”

“Paris Without You” cast a brilliant light that radiated in Carnes’ phrasing. “Time will fly, we’ll drive on by,” she sang, her voice suddenly airborne as a flute solo by Tim Weisberg swirled into the foreground. “That vocal performance was part of a magical night,” says Moore. “Kim finished all of the lead vocals for the whole album in one evening. As a producer, I was pretty impressed by that. She was really nailing it. She was always that way, though.” Like Jerry Wexler before him, Moore witnessed a pro in peak form behind the microphone.

Carnes amplified the meaning of “Paris Without You” by coupling the album title with the title of the song. She explains, “When I was in high school in Pasadena, I discovered this alley in downtown LA where nobody really went in those days. There was a department store called Bullock’s and the alley was between two Bullock’s stores. Above the alley, there was a walkway that went from one store to the other. The alley was like a French street.

“I walked down the alley. It looked so romantic and French and wonderful. The first thing I saw were lilacs in an outdoor florist. I’d never seen that before. I said, ‘These are so beautiful. This looks like how Paris must look.’ There was an espresso bar. It was years before espressos and lattes became in vogue. People were drinking espresso in Europe, but not in the states. I started getting my little cup of espresso and I’d always buy a bunch of lilacs. The name of the alley was called St. Vincent’s Court, hence the name of the album.”

St. Vincent’s Court was already mastered by the time Carnes wrote what EMI would select as the album’s first single, “It Hurts So Bad”. She recalls, “All of a sudden, that song came out of me. Jim Mazza said, ‘Run in and record that. I don’t care if the album’s mastered. That’s a hit!’ Everybody felt so strongly about it that we released St. Vincent’s Court a little later to put ‘It Hurts So Bad’ on the album.” The song featured a rugged yet robust vocal from the singer. “Kim’s got that little edge to her voice,” says Cuomo. “She can regulate the intensity of a performance by laying into it a little bit and giving you a little more of that gravel. I love that about it.”

EMI released St. Vincent’s Court a full year after signing Carnes. In between, the singer’s duet version of “You’re a Part of Me” with Gene Cotton had spent three months on the Hot 100 and Barbra Streisand covered her second Carnes tune “Stay Away” on Songbird (1978). “It Hurts So Bad” debuted on the Hot 100 the week ending 24 February 1979 and would peak at #56 two weeks later. Though St. Vincent’s Court may not have climbed the Billboard 200, Carnes was about to embark on a songwriting project that would begin her first of many visits to the top of the country charts.

Since venturing solo from his days in the First Edition, Kenny Rogers had become a superstar with equal draw to pop and country audiences. “Lucille”, “She Believes In Me”, and “You Decorated My Life” were just a few of the hits that made him a mainstay on Top 40 radio in the late-’70s. Rogers approached Carnes and Ellingson about composing a concept album for his next release. “That was an extraordinary opportunity as songwriters,” says Carnes. “I put it in the perspective of today if Tim McGraw said, ‘I want you to write me a whole album.’ Kenny was selling millions and really on top of his game. He said, ‘I want to be a modern day cowboy. Run with it.'”

The duo created Gideon Tanner and wrote a complete back story for the character. “He was a bit of a rogue,” says Carnes. “He was in prison for cattle wrestling. He had a love interest. The album spans his life. It starts with his funeral and it ends by a campfire.”

Carnes and a cadre of her favorite musicians demoed the album at A&M studios, with Kin Vassy singing lead vocals. “To this day, I love the album we made,” she says. “Kin was the most amazing singer. We did ‘Don’t Fall In Love With a Dreamer’ as a duet. It came out so good. We went to Kenny’s house and we played him the album. After ‘Dreamer’, he said, ‘If I decide to do this, will you do this as a duet with me?’ ‘Yes, I think so.’ [laughs] We all flew to Nashville and recorded the album.” Alternately sweet and soulful, “Don’t Fall In Love With a Dreamer” would be the song that introduced many listeners to the legend of Gideon.

Produced by Larry Butler, Gideon (1980) was a masterfully composed album that Carnes and Ellingson tailored to Rogers’ interpretive strengths. “I knew Kenny’s jazz voice from listening to the early Bobby Doyle Trio albums,” says Carnes. “We wrote ‘One Place in the Night’ especially for that space in his voice. That, to me, is jazz-rooted Kenny Rogers, which most people didn’t know. I loved his vocal on that.”

Gideon continued Rogers’ reign, spending seven weeks atop the country albums chart. “Don’t Fall In Love With a Dreamer” bowed on the Hot 100 the last week of March 1980 and soared to number four in the middle of its five-month run on the chart. After scoring her first Top Five single, Carnes had more reasons to celebrate when “Don’t Fall In Love With a Dreamer” earned a Grammy nomination for “Best Pop Performance by Duo or Group” the following February.

“Don’t Fall In Love With a Dreamer” marked a commercial crossroads in Carnes’ career that led to Romance Dance (1980). Working with producers George Tobin and Mike Piccirillo, Carnes fueled her second EMI effort with a feverish cover of Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman’s “Tear Me Apart” plus tuneful originals like “Swept Me Off My Feet (The Part of the Fool)” and “In the Chill of the Night”. Produced by Daniel Moore, “Changin'” featured Carnes on piano while Kin Vassy and Herb Peterson lent their crystalline harmonies to the mix.

However, the album’s crowning moment arrived on the opening cut of Side Two. Carnes sumptuously crooned a series of “ooh’s” before the lyrics kicked in. “Let it be soon, don’t hesitate” she sang, words that Smokey Robinson & the Miracles fans would recognize as the opening line to “More Love”. “I’d wanted to do ‘More Love’ forever,” says Carnes. “I’d been singing that song for so many years. Ever since the first time I heard Smokey’s version of that, I said, ‘When I start recording, I’m going to record that song.’ I love it!”

It was Bill Cuomo who outfitted “More Love” with the synth-based intro that became the song’s calling card. “The brilliant Bill Cuomo was just noodling around with this little classical thing,” says Carnes. “We went, ‘Wait a minute! What if you did that and we made it a pre-intro?’ I think it was the most brilliant set-up that he played and wrote to that song. To this day when I do it live, the minute that [sings intro melody] starts, people know what it is.”

Carnes closed Romance Dance by revisiting “And Still Be Loving You”, one of the jewels from her first A&M album. “I loved that song,” she says. “I thought it had gotten overlooked. I wanted it to be heard so much. My publisher and I had tried so hard to get that cut covered. I think it’s pretty timeless.” Cuomo accompanied Carnes on acoustic piano and steeped the song in a mist of synthesized strings. The singer struck a balance between strength, sensitivity, and unbridled yearning. Seldom do artists succeed in covering their own material, but Carnes matched, and perhaps exceeded, the power of her original.

EMI enlisted engineer par excellence, Val Garay, to mix Romance Dance and slated the album for a summer release. After a steady two-month climb on the Hot 100, “More Love” peaked at number ten the week ending 16 August 1980 — the same week that Romance Dance peaked at #57 on the Billboard 200. “DJs loved ‘More Love’ because they could talk and do their whole thing — ‘And now … Kim Carnes!’ — with this little classical music background,” says Bill Cuomo. “They’d time it to where they could look pretty cool themselves.”

Carnes was already at work on her next album when her version of the Box Tops’ “Cry Like a Baby” reached #44 during November 1980, right alongside her guest appearance on Randy Meisner’s “Deep Inside My Heart”. Between the success of “More Love” and her duet with Kenny Rogers, the singer had scored her first major hits. Now she was about to score her first blockbuster.

“Kim Can Paint the Dark and Mysterious”

“I have always loved recording live,” says Kim Carnes. “I like giving my best vocal with the band’s best take. That’s it. I don’t like overdubbing. I don’t want my vocals pieced together. I would never let that happen. I think for me to get the right emotion — just for me, it’s different for everybody — I need to sing a song start to finish.” That philosophy would be an essential component to the success of Mistaken Identity (1981).

Carnes had cultivated a good rapport with Val Garay when he mixed Romance Dance and asked him to produce her third album for EMI America. “Val was a very successful engineer at that point, engineering Linda Ronstadt and James Taylor’s albums,” she says. “I loved the sound of those records.” Garay welcomed the gig. “I loved Kim as an artist,” he says. “The first thing I started doing was looking for songs. As much as I loved her writing, she also was great at covering other’s songs. I put her together with Eric Kaz and Wendy Waldman and she wrote a great song with them, ‘Still Hold On’. I produced a band in the late-’70s called the Funky Kings, which was Jack Tempchin, Jules Shear, and Richard Stekol. Richard wrote a song on that album called ‘My Old Pals’. Kim did a great rendition of it, of just her and piano.”

Interestingly, a song that Jackie DeShannon and Donna Weiss wrote had recently re-surfaced after Carnes first heard it during the Romance Dance sessions. The song was “Bette Davis Eyes”. Carnes recalls, “George Tobin had played me a Jackie DeShannon demo that was completely different. It was all major chords, not minor, but the lyric killed me. Just the title — a song called ‘Bette Davis Eyes’? I’m interested! I kept saying to George, ‘I want to do that song!’ All of a sudden, it disappeared and he kept changing the subject.

“I started writing for Mistaken Identity. Donna Weiss, who wrote all the lyrics, called me and said, ‘Is it true that George Tobin played you ‘Bette Davis Eyes’ and that you really loved it?’ I said, ‘Yes! Oh my gosh, I’d forgotten about it.’ She said, ‘Well, the reason why George never brought it up again is because he came to me and said that he could get you to do this song if we gave him half the publishing. Jackie and I wouldn’t do it.’ Thankfully, it didn’t happen. It wouldn’t have been anything like the record it turned out to be. Not even close.”

Garay liked the idea of cutting the song, especially since he’d worked with Jackie DeShannon when he lived in San José during the ’60s. “I’d put a band together to back her in a club called the Loser’s North,” he recalls. “She was managed, at that time, by her father. I had been involved with her early on and knew that she was a folk singer. I just basically sat down with an acoustic guitar and started playing around with ‘Bette Davis Eyes’ like a folk song.” It would be the first of several attempts to recast the song for Carnes.

“I wanted ‘Bette Davis Eyes’ to be dark and mysterious like the lyric,” says Carnes. “We rehearsed it for three days trying to figure out, How are we going to do this? We tried it every way.” Cuomo continues the story, “I stopped us in the middle of about the 40th run-through and I said, ‘This sucks. It’s awful.’ Then everybody looked at me. I said, ‘It needs something, like a riff.’ Kim and Val said, ‘Like what?'” Stationed behind the Prophet-5, Cuomo played what became the song’s signature motif, introduced at the very beginning of the record. “I was looking for a sound that was kind of spooky and eerie to draw into the mystique of the ‘Bette Davis Eyes’ thing,” he says. “I just kind of reached somewhere and pulled it out of a hat!”

Cuomo’s riff silenced the room. “Everybody stopped,” says Carnes. “We all went around Bill. It was right before digital synths came out, so it still had a beautiful, warm analog sound. I just said, ‘Oh my God. That’s it! That’s how we do it.” Cuomo adds, “We sent the band on break. For the next two hours, Kim and I and Val ran through it until we could re-write it around that riff. I remember Waddy Wachtel said to me, ‘Cuomo, how you got this from that, I will never ever know … and I don’t want to!'” [laughs]

The new riff kindled other musical ideas. Carnes continues, “I said, ‘How about a lick from Goldie (my other keyboard player Steve Goldstein) like the one in ‘Cars’? What I meant was the keyboard lick in Gary Numan’s record called ‘Cars’. My drummer Craig Krampf thought I’d said, ‘the Cars’ so he went out and got the synare because the Cars had used that trash drum sound. A wonderful misunderstanding came up with the trash drum sound on ‘Bette Davis Eyes’. Goldie wrote the keyboard part that’s the counterpart to Cuomo’s.” In mere hours, “Bette Davis Eyes” had traveled 180 degrees from its original source.

Carnes had one more task. “I thought, Now that it’s perfect, I’ve got to figure out how to sing this,” she chuckles. “It was like something just jumped into my body and I knew exactly how to sing it.” Cuomo perfectly distils the essence of her interpretation. “Vocally, Kim can paint the dark and mysterious,” he says. “She plugged right into that and got it right away.”

With the tape rolling, Carnes and her band were in sync with each other. “Everybody that was playing on ‘Bette Davis Eyes’ was playing live,” says Garay. “Kim was singing live. There were no overdubs at all.” Carnes continues, “The tape was our second take. I wanted to take home all the songs we did before Christmas break. Niko Bolas, Val’s second engineer, did a rough mix of ‘Bette Davis Eyes’ and that is what ended up being the record.” Carnes, Garay, and the band were into total agreement — nothing could beat the rough mix.

Carnes’ self-penned “Mistaken Identity” endured a similar process of reinvention. “I love that song so much,” she says. “It started out more R&B and uptempo. I had me, Maxine, and Julia doing backgrounds on it. It sounded great in rehearsal. We cut it. We all listened to it and said, ‘It doesn’t sound right.’ We went to another song. At about three in the morning, Bill Cuomo — it’s always Bill! — was out in the studio alone on his keyboard. He slowed it way, way down and got this incredible feel to it that was pure magic. I started singing in the room. One by one, my band came out, picked up their instruments, and started playing. Val said, ‘We got to get you in the vocal booth.’ I said, ‘No, I’m not moving from here. We have to record it just like it is.'”

Cuomo’s introduction to “Mistaken Identity” simulated the sound of midnight, while Carnes phrased the melody with the slinkiness of a spider weaving a web. “Everything was live,” says Cuomo. “That’s the only way it could go down because all of the mics were open. It was one of those goose-bump moments.” Carnes and her band basked in the song’s allure. “We listened to that until seven in the morning,” she says. “Everybody in that room said, ‘This is the most magical record we’ve ever been a part of.’ It was just incredible. My manager, at the time, said, ‘But can you do it again?’ Waddy Wachtel was in the room and said, ‘Fuck no! Who’d want to?’ It was the perfect response.”

If Mistaken Identity dealt a full deck of musical moods, then “Draw of the Cards” was the album’s joker. “It was more of a musical experience as opposed to a pop song,” says Garay, who’d inspired the song’s title during a conversation with Carnes. The track itself sprung from Cuomo. “I was just jamming and this riff kind of fell out one day,” he says. “I said, ‘Hey guys, this is kind of weird’ but I sent it to them.” The groove culminated in a maniacal laugh courtesy of Dave Ellingson. Amused by the memory, Cuomo recalls, “I looked at Dave and said, ‘Where’d that come from?'” Hypnotic, sleek, and playfully sinister, “Draw of the Cards” took Mistaken Identity several steps further into uncharted territory.

EMI issued “Bette Davis Eyes” in March 1981. With AC-oriented hits by Styx, REO Speedwagon, Eddie Rabbitt, and Don McLean dominating the Top Ten, Carnes’ single sent a shiver through the airwaves. “There was nothing that sounded like that,” Garay declares. “The week that ‘Bette Davis Eyes’ was released, Kim, Dave, and I were sitting in my office and we heard it on the big station in LA. We thought, Let’s call in like fans and request it. We called in from the phone in my office and actually got the DJ on the phone. We said, ‘We really want to hear that Bette-Davis-whatever-that-thing-is again.’ The guy said, ‘If I get one more request for that song, I’m going to hang up the phone!’ He was bombarded!

“Usually in the first week, back in those days, if you got 50 percent of the P1 (top rated) stations in America, you could pretty much guarantee yourself that you got a Top Ten hit. There were 132 possible stations and we got 111. The head of promotion at EMI said he didn’t have to spend a dime. It just took off on its own.”

“Bette Davis Eyes” also had something else going for it — a music video. Five months before MTV launched in August 1981, and forever changed the music industry, Carnes met with Jim Mazza to discuss possible video directors. She recalls, “We watched three days of videos, trying to find somebody that was going to be right for ‘Bette Davis Eyes’. When we saw Russell Mulcahy’s video of Classix Nouveaux’s ‘Guilty’, we both looked at each other and went, ‘That guy!’ That’s so different and bizarre.

“‘Bette Davis Eyes’ was the first video Russell did in this country. His vision along with that record was the perfect marriage. He said, ‘There’s a movement in Britain right now called the New Romantics. That’s what this should be.’ Nobody in this country had heard of the New Romantic movement. He got all the extras and dressed them in the clothes.”

Before Mulcahy ever went on to direct videos for Fleetwood Mac (“Gypsy”), Rod Stewart (“Young Turks”), Queen (“A Kind of Magic”), Billy Joel (“Pressure”), the Motels (“Only the Lonely”), and several clips for Elton John (“I’m Still Standing”) and Duran Duran (“Rio”), he created the striking visuals that turned “Bette Davis Eyes” into a veritable fashion show of flamboyant New Romantic ensembles. Even the influence of designer Vivienne Westwood’s “Pirates collection” (1981) was evident in the band’s attire.

Beginning 16 May 1981,”Bette Davis Eyes” would hold the number one spot on the Hot 100 for nine weeks. By June, both the single and Mistaken Identity had reached gold certification. A month later, Mistaken Identity went platinum and crowned the Billboard 200 for four weeks, spending a total of 52 weeks on the charts.

Kim Carnes won national coverage beyond the usual music trades. Newsweek called the singer’s voice “a hoarse shrug of pleasure that pumps some lust into Bill Cuomo’s brilliant clockwork arrangement. On ‘Bette Davis Eyes’, she haunts a make-believe world of intrigue and romance that fades with the record and keeps you coming back for more — the most seductive pop single in years” (21 September 1981). In his New York Times review of Carnes’ appearance at the Savoy, Stephen Holden noted the singer’s revamped image into “a more combative rock-and-roller” who “convincingly portrays a swaggering female roustabout” (26 August 1981).

The impact of “Bette Davis Eyes” traveled well beyond the US. “I have a framed full-page ad that showed it number one in 31 different countries,” says Garay. “I remember when EMI had a party for us. It was at a club on Sunset in Hollywood. The whole stage was covered with a curtain. When they opened the curtain, the entire wall was covered with gold and platinum records from around the world.”

EMI America continued the promotional push for Mistaken Identity, releasing both “Draw of the Cards” (#28 pop) and the title cut (#60 pop) as follow-up singles once “Bette Davis Eyes” completed its six-month stint on the chart. Mulcahy conceived an almost hallucinatory storyboard for “Draw of the Cards”. A colorful array of magicians, mediums, dancers, and carnival characters greeted Carnes before she descended into a subterranean world where a menacing, fork-tongued monster stood in waiting. “We filmed the video in a place that most people don’t know about,” she says. “It’s an old subway that used to exist under the bowels of Main Street in downtown LA.”

On 24 February 1982, the Shrine Auditorium set the scene for the pinnacle of Carnes’ journey with Mistaken Identity when she attended the 24th Annual Grammy Awards. Only a year after she’d received her first nomination, Carnes was now a contender in top categories, including “Record of the Year”, “Album of the Year”, and “Best Pop Vocal Performance, Female”. Val Garay received a nomination for “Producer of the Year” while Donna Weiss and Jackie DeShannon were frontrunners for “Song of the Year”.

Kenny Loggins and Pat Benatar presented the “Record of the Year” category. Though John Lennon’s “(Just Like) Starting Over”, Bill Withers & Grover Washington, Jr.’s “Just the Two of Us”, “Arthur’s Theme (the Best That You Can Do)” by Christopher Cross, and Diana Ross & Lionel Richie’s “Endless Love” were all strong nominees, the theater erupted in applause when Loggins announced “Bette Davis Eyes” as the winner. Accepting “Record of the Year” with Garay, Carnes congratulated Weiss and DeShannon on winning “Song of the Year” earlier in the evening and paid tribute to the woman whose name was now forever immortalized in pop music. “What a night,” Carnes exclaims years later. “EMI had a party. My band was there and we just celebrated all night. I couldn’t have been happier!” It wouldn’t be the singer’s last time taking home the industry’s most coveted prize.

“Dance Till It Makes You Feel Good”

While “Draw of the Cards” might have been regarded as a quirky, left field curio on Mistaken Identity, it would have been right at home on Voyeur (1982). In style and content, the album set an edgier tone than its predecessor. Even the artwork made a bold visual statement. “The cover was based on Metropolis (1927),” says Carnes, who posed like a statue against the backdrop’s imposing architecture.

Carnes powered Voyeur with new wave sensibilities, adapting the sonic aesthetics of UK bands like A Flock of Seagulls and Classix Nouveaux to her own palette. “All of those wonderful synth English records were just starting to come here, so I was taken by all of it,” she says. “That period became a huge influence on me. That’s what I was into then. I couldn’t have been more passionate about the music at the time.”

A sense of fun and experimentation clearly informed Carnes’ approach to the material, especially on tracks like “Merc Man” (one of her favorites) and “The Arrangement”, which featured Martha Davis of the Motels on guest vocals. Both “Say You Don’t Know Me” and Carnes’ cover of “Looker” by Sue Saad & the Next featured some of her most commanding vocals while “The Thrill of the Grill” dialed up a dose of boisterous rock and roll.

An aura of mystery enveloped the title character in “Voyeur”, a woman who cavorted in shadows, consumed by a pleasure-seeking beat. Carnes recalls how the track evolved. “Duane Hitchings is a super-talented writer and keyboard player,” she says. “He wrote a lot of Rod Stewart’s hits. He would send me tracks and I would write the words. I’d pick the tracks that inspired me. I kept hearing his lick on the chorus over and over again and just started singing “Voyeur, voyeur are you hot tonight‘. It all just came from there.”

EMI America released the title track during the summer of 1982. Though “Voyeur” only peaked at #29 on the Hot 100, it went to number two in France and made the Top Ten in other European markets. “Europe was so refreshing,” says Bill Cuomo. “They didn’t have so many boxes to put things in. If it was good, they played it.”

A full year after MTV launched, Russell Mulcahy shot a video for “Voyeur” that was far removed from the stylish New Romanticism of “Bette Davis Eyes”. His camera followed Carnes through smokey bars and deserted alleys after she glimpses an assault. “MTV would only play the video at night because there was a slap in it,” she says. “They said it wasn’t appropriate for daytime audiences.” The video ended with a cliffhanger, freezing Carnes’ own fate in the final frame.

The press tended to assess Voyeur in reference to Mistaken Identity rather than accept the album on its own terms. Billboard called it “A worthy follow-up to a widely admired LP” (11 September 1982) while People Magazine noted “Carnes’ gritty voice is often magnetizing … and her own lyrics are still nothing if not clever” (25 October 1982). “We did the best job we could,” says Garay. “It’s a great record, no question about it. We did a great job together.” Though the title track earned Carnes a Grammy nomination for “Best Rock Vocal Performance, Female” and “Does It Make You Remember” made the Top 40 in January 1983, Voyeur landed at a more modest #49.

Ultimately, the album found a more receptive audience outside the US. Carnes explains, “Over the years, a lot of people have said the Voyeur album was big in Europe and South America because they could accept it, but in the states, it was ahead of its time. True or not, I don’t know, but I sure loved it at the time. I was so proud of that album.”

Throughout the ’80s, Kim Carnes would appear on several soundtracks, including Spaceballs (1987), which featured her duet with Jeffrey Osborne, and Rude Awakening (1989). However, it was Carnes’ collaboration with Craig Krampf and Duane Hitchings on “I’ll Be Here Where the Heart Is” that helped set the backdrop for a pop culture sensation, Flashdance (1983).

Phil Ramone was one of the film’s music supervisors. “Phil was such a wonderful, respected producer,” says Carnes. “He lived in New York so we didn’t see each other often, but we’d been friends for years. He came to me and said, ‘I want you to come see a rough cut of a movie and I want you to write something for it.’ Giorgio Moroder was also doing the music. We were friends, too. I saw Flashdance. I knew there was a place for one ballad and wrote ‘I’ll Be Here Where the Heart Is’. I sent it to Phil and he said, ‘This is perfect. I love it.'”

Upon the film’s opening in April 1983, Casablanca Records released the accompanying soundtrack. It sped up the charts to number one, supplanting Michael Jackson’s Thriller (1982) from the top. Both Irene Cara’s title theme “Flashdance … What a Feeling” and Michael Sembello’s “Maniac” topped the Hot 100. The soundtrack went multi-platinum in just a matter of months and would earn Carnes her second Grammy Award when it won “Best Original Score” in February 1984.

Despite steadfast interest and support from Casablanca president Russ Regan, the label was not permitted to release “I’ll Be Here Where the Heart Is” as a single for the U.S. market. Instead, Carnes won validation of another kind when Tina Turner added the song to her concert set. “It was all heart,” notes Carnes about Turner’s rendition. “It was so great.” At the time, Turner was just on the verge of a major comeback with Private Dancer (1984), which magnified the emotional resonance of her performance.

The two singers actually shared a long history together, dating back to Carnes’ background vocals on Acid Queen. In recent years, they’d been featured guests during Rod Stewart’s ’81 tour of North America. The trio’s performance of “Stay With Me” later appeared on Stewart’s Absolutely Live (1982) album. As Turner began vetting material for her comeback, she demoed Carnes’ “Undertow” from the Voyeur album. “Her ‘Undertow’ is crazy good,” Carnes exclaims. “Whenever I would see her around that time, she’d always say, ‘Oh girl, that song … I love it!'”

Carnes’ own solo career resumed with Café Racers (1983). EMI America teamed her with producer Keith Olsen, who enlisted outside studio players for the session. “I had a killer band,” she says. “We were a family and we’d had so much success together. He brought in all of these players who I didn’t know and had no rapport with. Not to take anything away from them — they were wonderful — but they weren’t my band. Part way through that album, I gradually got some of my people back — I got my sax player back, I got Cuomo back — but never my whole band.”

Amidst the glossy production, Café Racers served up its share of infectious tunes. Martin Page and Brian Fairweather collaborated with Carnes and Ellingson on the album’s propulsive opener, “You Make My Heart Beat Faster”. Carnes teamed with Cuomo on “Hurricane”, a song expertly crafted for the clubs, while the duo brought Ellingson aboard for “Universal Song”, which included the line that spawned the album title. Elsewhere, Carnes ventured into rock-tinged pop (“Young Love”), smokey, mid-tempo grooves (“Kick in the Heart”), and ambient ballads (“Met You at the Wrong Time in My Life”), the latter co-written by Classix Nouveaux member B. P. Hurding.

Though Café Racers only dented the Billboard 200, its string of singles found moderate success. Page and Fairweather’s “Invisible Hands” peaked at #40 in November 1983 and earned Carnes another Grammy nomination for “Best Rock Vocal Performance, Female”. “You Make My Heart Beat Faster” followed at #54 in February 1984 and “I Pretend” (another Page / Fairweather effort) capped the album’s run with a solid Top Ten placement on the Adult Contemporary chart in June ’84.

Looking back, Carnes cites “Hangin’ On by a Thread (A Sad Affair of the Heart)” as her personal favorite on the album. “John Waite came in and sang the duet,” she says. “I love that.” Indeed, the two singers made the emotions palpable as they harmonized above the song’s dramatic yet sparsely orchestrated production.

Read the rest of Christian John Wikane’s interview with Kim Carnes in part two.

- Where the Heart Is: An Interview With Multi-Grammy Winner Kim ...

- Where the Heart Is An Interview With Multi-Grammy Winner Kim ...

- Where the Heart Is An Interview With Multi-Grammy Winner Kim ...

- Where the Heart Is: An Interview With Multi-Grammy Winner Kim ...

- Where the Heart Is: An Interview With Multi-Grammy Winner Kim ...

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)