There’s a reason Lynda Barry is the first comics artist to win a MacArthur “Genius” Award. Though I’ve been her fan for years and have taught her graphic memoir One! Hundred! Demons! (2005) in my classes, her excellence in the comics form does not place her above the many other equally excellent comics creators out there. Barry is also an extremely well-regarded educator who has developed an idiosyncratic pedagogy for comics, but even that doesn’t distinguish her from other great comics artists with equally impressive teaching creds.

What does make Barry such a deserving comics “genius” doesn’t have much to do with comics. Making Comics, though obviously publishing post-award, is all you need to understand why the foundation selected her for the honor.

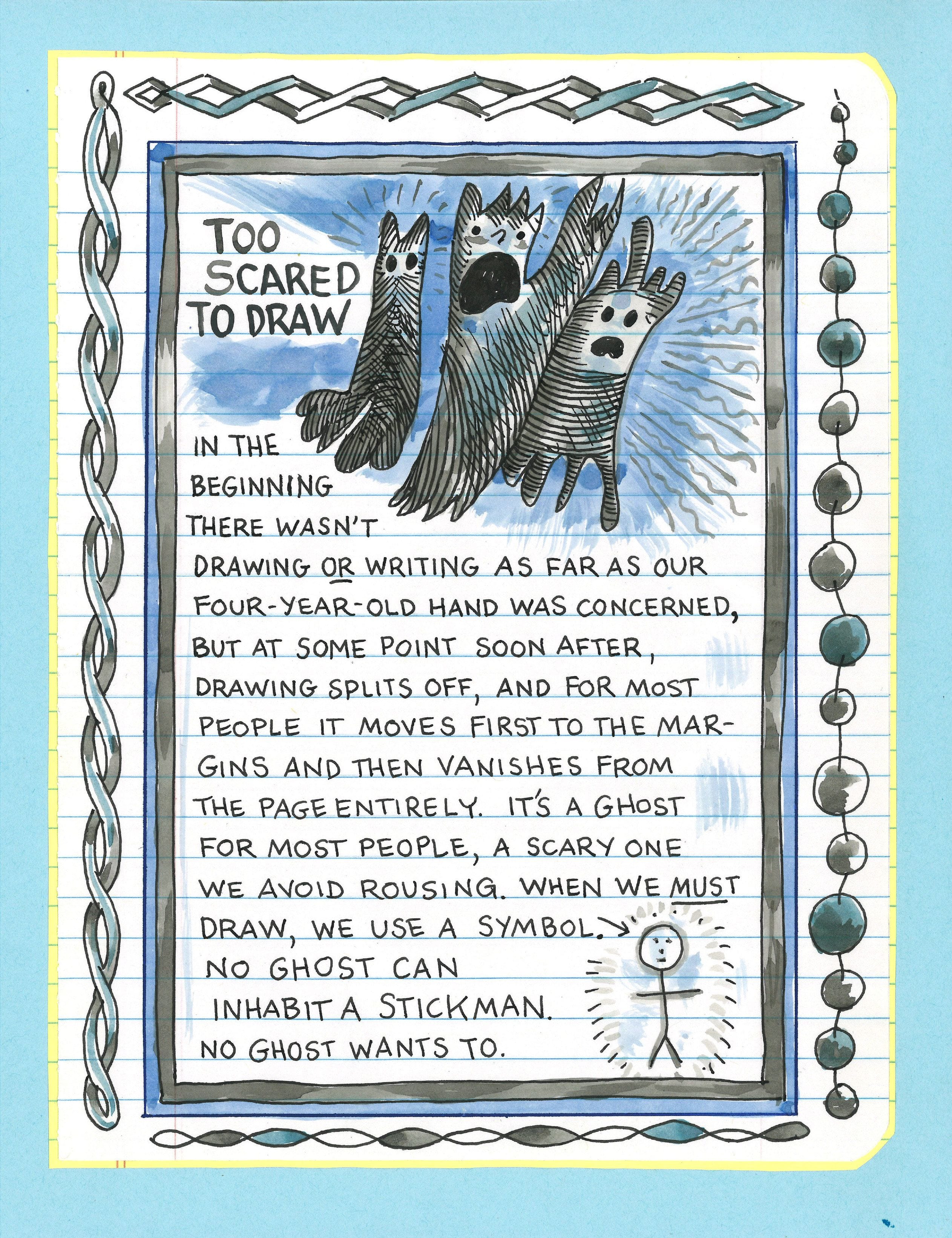

If you’re at all familiar with her past work, you’ll recognize the book as a Barry book at a first glance. Like its predecessor, Syllabus (2014), Making Comics is printed to look like a classroom composition notebook, complete with a center-stitched binding and lined pages. It also looks like a one-of-kind, as if you’ve stumbled upon the only existing, hand-drawn copy that Barry made herself. The effect is emphasized by her doodle-like aesthetic that incorporates not only her loose, first-and-only-draft style of cartooning, but also the abstract shapes etched along the page edges as if she had pored over the notebook with the daydreamy meticulousness of an actual doodler.

Every page is wonderfully crammed. There’s even a revise-as-you-go quality, since some of the hand-written text includes cross-outs and insertions. These are details we would normally register as mistakes, but here they are integral elements not only of the artwork, but of Barry’s larger vision.

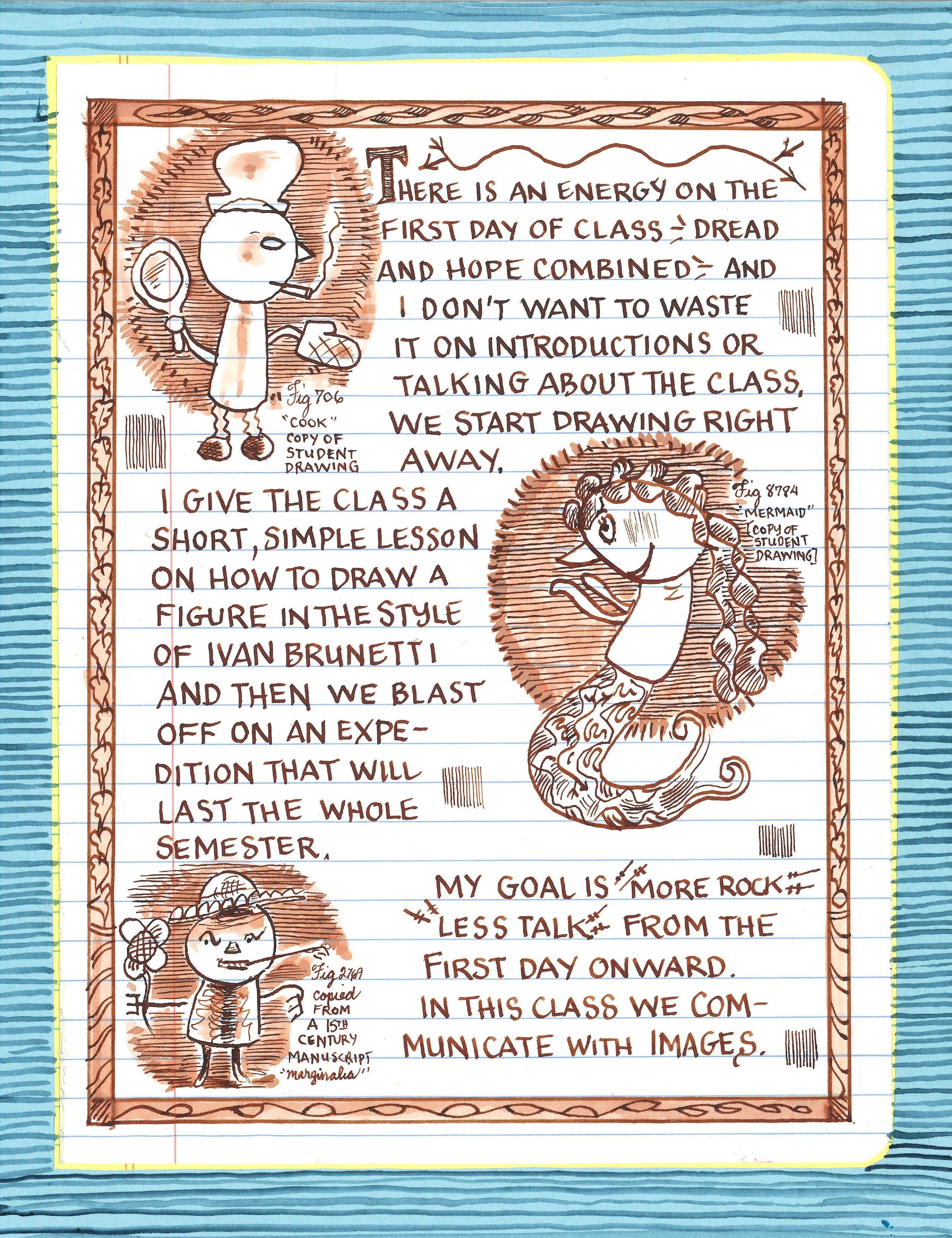

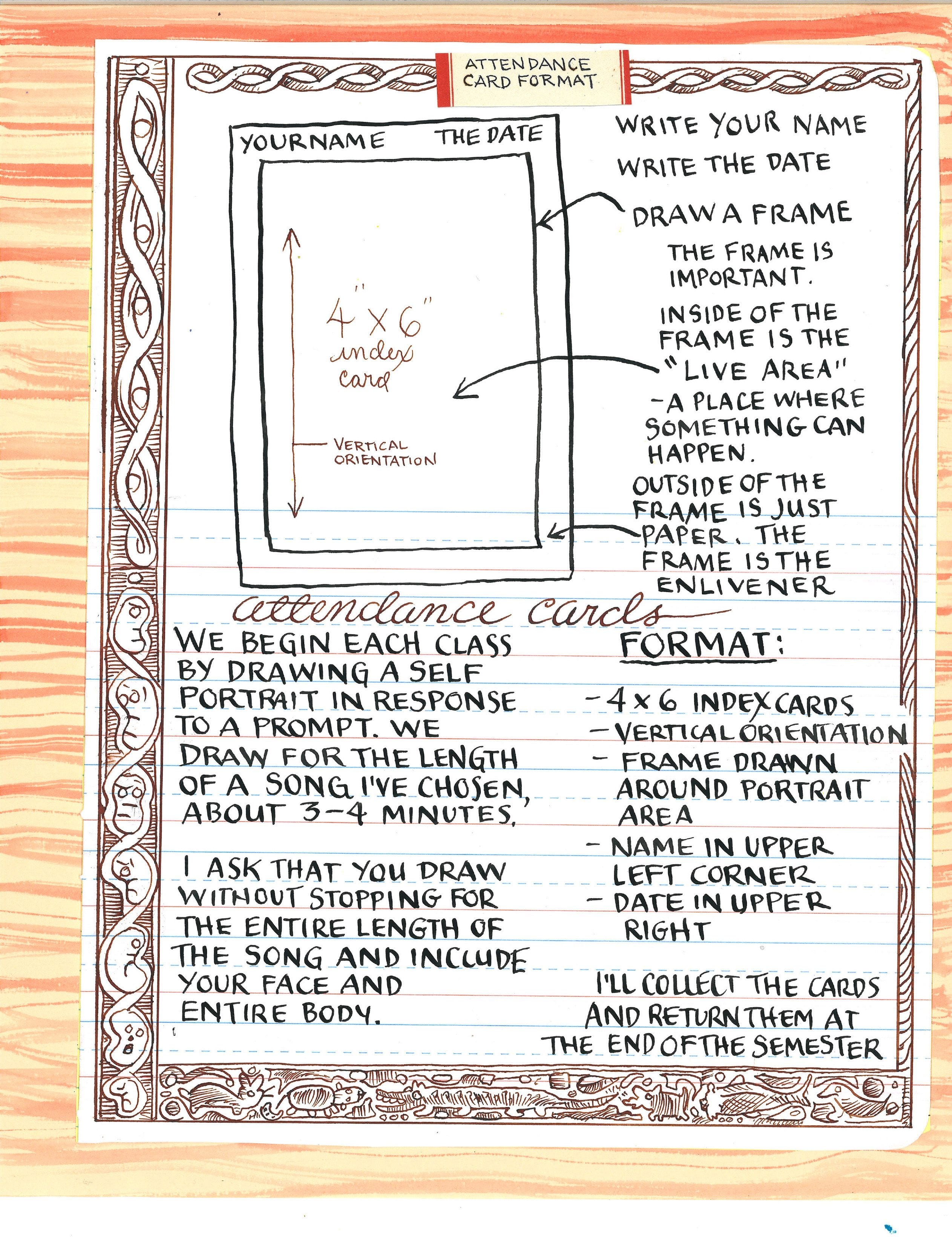

Once you begin reading (and it’s a surprisingly word-heavy book), you’ll realize you’ve entered a document made from an actual classroom. Some of the opening pages could be the handouts students receive on the first day of the semester. Later pages could be the assignments passed out at the end of each class. They include: drawing quickly, drawing with your eyes closed, drawing with your non-dominant hand, drawing with both hands simultaneously, drawing in tandem with a partner, drawing fragments with multiple partners, drawing images out of coffee stains and scribbles.

Making Comics is more than exercises though. Barry provides her personal, free-form lectures too, taping in drawings by former students (some of them rescued from discards on the floor), to create as immersive a document as possible. If you can’t take a class with Barry, Making Comics is the next best thing.

But what kind of class is it?

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

The odd thing about Making Comics is that it’s not really about making comics. That’s not a criticism. If you’re looking for a how-to textbook on the comics form, there are plenty already out there (e.g., Scott McCloud’s 1993 Understanding Comics). And (full disclosure) I’m in the process of co-authoring a book based on my comics class, as well. Not surprisingly, I think my forthcoming book significantly improves on all the others (otherwise why write it?). Except for Barry’s, because Barry’s isn’t, ultimately, a how-to textbook.

Yes, Syllabus takes the form of one, and, yes, an instructor could teach a class following its daily assignments, but the results and, more importantly, Barry’s deeper concerns are not about comics. Comics are just a handy medium, one that has been so widely denigrated as bad art, lowbrow art, and non-art that those connotations align with her project of freeing her students from false assumptions about the nature of “art”, and the importance of making it for themselves.

As a professor, I was delighted by the specificity of her approach, down to the minutia of her attendance policy (you’re damn right three tardies equal an absence), but such details serve a larger purpose. Readers aren’t getting graded. What they are getting is an immersion into Barry’s philosophy of art and — this is going to sound a bit grandiose but I’ll say it anyway — life. Barry teaches us how to be better people by teaching us how to see and think and draw like children again.

She loves children. Making Comics is a love letter to every child who ever picked up a crayon and started making marks with unselfconscious intensity. Those children include her college students. Like her readers, some arrive at class with artistic training and some arrive with none at all. The latter arrive having long forgotten the uninhibited style of image-making they understood instinctively as children. Finding each of those children is Barry’s mission, and she is very very good at it.

I’ve read a lot of writing and drawing textbooks, and Barry’s is the only that has made me choke up with emotion. About a quarter into the book, she writes:

“Not a single drawing or line of my handwriting survived my childhood. I sometimes wonder if that’s why I hang onto the drawings my students leave behind. They are so alive to me. They give me something in the way a song I love gives me something. I can’t explain. Sometimes I copy them. Sometimes I draw on them, color them, cut them out. Almost all the pictures in this book are rescued images by students.”

I am moved by the intimacy and matter-of-fact vulnerability of those words and the volumes of meaning and unspoken experience they gently paper over, especially how the opening verb “survived” is echoed in the closing verb “rescued”. Later she writes about a class exercise:

“Sometimes we may encounter strong feelings and unexpected memories. We are free to follow them or to turn away from them or to change them with fiction. Sometimes we become unexpectedly emotional when reading aloud. We are always free to stop or to have someone else read it for us. And unless someone asks, we let any classmate recover on their own, allowing them the choice of privacy in the presence of classmates who lend silent support.”

In class, Barry requires everyone to assume a pseudonym that replaces their actual name for the entire semester. Hers have included: Professor Hotdog, Professor Peanut, Professor Skeletor, and Hot Stuff the Little Devil. When one of her former students described this approach to me a few years ago, I found it both silly and a little off-putting, as though Barry were depersonalizing her classrooms. She’s not. Instead, she’s found a way of becoming more personal, of accessing the unnamed and unnamable parts of ourselves, rediscovering the tiny fingers that understood everything there is to know about a piece of paper and a pencil.

Barry wants to rescue us all.

Will Making Comics help produce the next MacArthur-winning comics artist? I doubt it. I don’t even know if it will help to produce any published comics. That’s not Barry’s goal. No matter your goal, you’ll benefit from reading this work.

- On Life in Graphic Detail - PopMatters

- The Best American Comics 2008 - PopMatters

- A Child's Scars from Bullying Are Laid Bare in a New Edition of ...

- 'Syllabus' Explores the Unconscious Mind in a Composition Book ...

- The Day of the Animals (1977) - PopMatters

- One! Hundred! Demons!, Lynda Barry - PopMatters

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)