Erroneously aligned with the blaxploitation movement of the 1970s, Melvin Van Peebles’ work, in the past, has often been overlooked in the more popular canons of film. His feature-length debut was the French production The Story of a Three-Day Pass. Generally ignored upon its initial 1967 release, the film served as a training ground for the young director who was in the early stages of experimenting with form. In the ensuing years, Peebles’ work has gained considerable traction. The Black Lives Matters movement has ensured that some of the most valuable and esteemed authors of film – regardless of their levels of renown – are being recognized for their longstanding contributions.

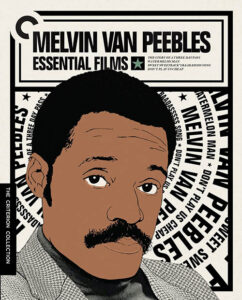

Criterion collects Peebles’ most notable works in a box set that highlights much of the director’s output in the ‘70s. Of the four films, some will be better known than others. But each film carries a powerful aesthetic that has defined both output of the authoring filmmaker and the eras in which these films made their debuts.

Power in the Candor of The Story of a Three-Day Pass‘

The Story of a Three-Day Pass,(1967) based on the director’s French novel La Permission (1967), takes its stylistic cues from the works of Nouvelle Vague filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. Turner, a Black American soldier (played by Harry Baird) is stationed in France and is up for a promotion. Given a three-day pass by his superiors, Turner wanders Paris looking for ways to spend his time.

In visiting a number of the city’s locales, he happens upon a nightclub where he meets the affable, young Miriam (Nicole Berger), a white French woman who speaks some English and takes an immediate liking to Turner. After a few spins on the dancefloor, the two grow amorously close and make plans to visit Normandy beach. A deepening bond between the two suggests more than just a casual affair, but their happiness is challenged by the disapproval they receive from onlookers.

Miriam is not quite astute in the matters of race and racism and much of the subtle condemnation escapes her. Turner, however, is highly aware of the insinuations and begins to doubt the relationship. Trouble comes when Turner and Miriam arrive at Normandy beach and they run into a few of Turner’s fellow soldiers, who make it a point to report Turner’s dalliances with the white woman to their commanding officer – an act considered an indiscretion by the captain and one that could cost Turner his promotion.

The Story of a Three-Day Pass is simple and direct in its storytelling, but it holds a wealth of power in its candor. Purely character-driven, the narrative depends on the charm of the two leads; Baird in particular, who balances a genial sense of being with the weightier matters of racial injustice and prejudice. While the stylistic touches may seem derivative of Godard’s more celebrated works, Peebles employs them judiciously to evoke a sense of casual joy and carefree innocence; the film is peppered with the kinds of tropes common in the Nouvelle Vague films of the ‘60s, with jump-cuts, awkward but good-natured love scenes, and the obligatory dance sequence.

Where the story stands on its own is in the social commentary that takes place within the drama. The messages of racism and culture shock are never heavy-handed and that is down to Peebles’ gentle but firm handling of the subject matter and Baird and Berger’s interpretation of the material.

The Story of a Three-Day Pass is resplendent with a cool and calm beauty. Filmed in lustrous black-and-white, the film gains offbeat traction by the performances of the leads, with both the handsome and sweet-natured Turner and the unassuming and lovely Berger delivering honest and likable representations of Peebles’ characters. Though the filmmaker would go on to write and direct films that delved even deeper into the complicated matters of racism, The Story of a Three-Day Pass easily stands as one of his best works.

Watermelon Man, the Inverted Fairy Tale

The topical matters of race are probed even deeper in Peebles’ Hollywood feature Watermelon Man. Daring for its time, especially for a mainstream effort, Peebles tests the limits of the socio-political comedy with an audacious experiment. A political take on the Freaky Friday formula (the 1976 American fantasy-comedy film directed by Gary Nelson), Watermelon Man (1970) is the story of a white and hopelessly suburban family led by the bigoted Jeff Gerber (ingeniously played by Black actor Godfrey Cambridge in full-fledged makeup as a white man).

Brash, ignorant and unctuous, Jeff ignores his wife Althea (Estelle Parsons) and his two children in pursuit of the all-American dollar. While engaging in silly shenanigans, like racing the bus every morning to work, Jeff makes light of the civil rights movement, often placing blame for the street riots on the African American community. His liberal-leaning wife has a few things to say about Jeff’s callous attitude toward the racial division, but Jeff has little time for Althea’s concerns. After a day of work smarming his way through selling insurance and harassing the female staff at his office, Jeff wakes up the next morning to discover he has become a Black man.

Unable to believe the supernatural turn of events, Jeff engages in any number of foolish ways to try and turn himself back into a white man, like bathing in a tub of milk and applying stifling amounts of skin-lightening creams. Nothing seems to work and Jeff’s horror soon turns to sadness when he begins to understand the indignities experienced by those on the other side of the racial line. Soon, everyone in his life, including his family, his neighbors and his office colleagues, turn away from him and Jeff must learn to navigate the world as a racially profiled man.

Probably the most prescient of Peebles’ films, Watermelon Man, an inverted fairy-tale of sorts, merges slapstick humor with lighthearted surrealism to present the deeper issues of racial division. While at times it dangerously veers toward parody, Peebles keeps the more serious themes of the narrative always in his line of sight. What begins as a ridiculous and preposterous sendup becomes a thoughtful and meaningful meditation on the ideas of our places in this world.

Peebles takes the concepts of American suburban culture and perforates them with the dread of civil unrest so that we never truly sit comfortably even when the laughs come easily. A scene in which Jeff is coerced by his neighbors into selling his home and moving out of the neighborhood after he becomes a Black man bridges the horrific threat of lynching with a sudden turnaround of ironic humor. Peebles has successfully written a scene so winsomely awkward that it veils the deeper sadness of racial isolation.

The filmmaker further probes the racial debate by examining some of the pretenses of white support in the civil rights movement; Althea’s deeper and furtive prejudices begin to surface once she realizes that there is no chance her husband will become a white man again. Her prior accusation of Jeff’s racism toward the Black community is suddenly held before the reflexive, internal mirror that Jeff has now earned in his time living as a Black man. His wife, like many who are called on their hypocrisies, can no longer hide behind the political jargon that masks the more honest feelings about race and class systems.

At times, the film calls for the viewer to take a few steps back in order to view the bigger picture. Many elements begin to emerge from the kaleidoscopic clutter; characters whose behavioral tics foreshadow narrative turning points, a shift in the soundtrack to denote the newer dimensions of Jeff, and subtle and probing jokes that reveal themselves over time. Stylistically, Peebles casts his net wide in order to bag as many aesthetic tricks as he can pack into the film: Warholian-colored filters, Nouvelle Vague-styled jump cuts, silent-era film placards, and dialogue puns fashioned from the political humor of Dick Gregory.

With just enough jazz cadences to slightly skew its pop accessibility, Watermelon Man’s acerbic wit, on-point social commentary, and absurdist humor come together with remarkable poise. There is true development here, a narrative arc that sustains the fantastical premise with a handsome design, in which everyone from Kafka to Hans Christian Andersen is judiciously referenced.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)