One of the recurring viral video hits from CBS’s The Late Lae Show with James Corden is “Crosswalk: The Musical”. It’s a simple premise. Dressed in the costume of the chosen musical production, Corden and company reproduce a number from the Broadway play in question. He’s done songs from Beauty and the Beast, Phantom of the Opera, and Grease, among others. The simplicity of the premise takes nothing away from its entertainment value, and such was the case with an August 2017 recreation of several numbers from the 1967 Broadway classic Hair. Start with “Aquarius”, add some interstitial comedy, add the title track, then end with a pixelated “nude” (host Corden and his guest, Hamilton legend Lin-Manuel Miranda) rendition of the finalé “Let the Sunshine In”.

As entertainment, it’s harmless filler. As commentary about the staying power of this musical (lyrics by James Rado and Gerome Ragni and music by Galt MacDermot) it’s a little stronger. Corden doesn’t seem to be implicitly saying anything political by using these songs as entertainment fodder, but it comes at a time in America when the divisive nature of the social discourse seems to be having equally bloody consequences. Where 50 years ago it was about the war in Vietnam and the generation gap, today it’s about alt-right, white nationalists, veiled and coded words from White House officials to cover anti-Semitism and pure hatred of the “other”. We may have been letting the sun shine in for the past 50 years, but now the burning sensation is out of control.

Why does Hair still matter? How do the sometimes painfully innocent sentiments (including its being marketed as a “tribal rock musical”) match with the still deep moments? Can these songs still mean something for the Instagram/Facebook generation?

The story is fairly simple, which adds to its relatability. Claude Bukowski leaves his Oklahoma ranch for New York City, where he falls in with a tribe of hippies and free spirits. They include Berger, the nominal tribe leader, and Sheila, a privileged white girl who finds herself within the context of the movement to turn on, tune in, drop out. It is less about a clash of cultures and political ideologies so much as it’s about a search for identity and a need to define a family in the midst of wherever you find yourself. If Hair was, as the title proclaimed, a “Tribal Rock Musical”, the contemporary viewer might wonder if the tribe has expanded in 50 years. Are the drugs as important? Is sexual identity as clearly defined? Are songs like “Black Boys”, “White Boys”, and “Sodomy” as shocking today as they were in 1967, or are we beyond that? Does shock and outrage cancel out a catchy melody?

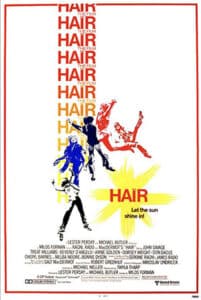

The 1979 film version, directed by Milos Forman and choreographed by Twyla Tharp, expanded the possibilities in ways only cinema could. Watch the police horses dance in Central Park to the beat of “Aquarius” in the opening number. Watch the businessmen walk in perfectly choreographed steps during “Where Do I Go?” After hippie tribe leader Berger ends up in Vietnam, switching uniforms with Bukowski so his Oklahoma friend can spend another day at home, Forman shoots the former (played by Treat Williams) singing the first part of “The Flesh Failures/Let the Sunshine In)” from the bowels of a troop plane. Cut from that to rows of crosses at a military cemetery as the ensemble sings the second half of the finalé, and the message is clear: life is expendable and war will rage on regardless of how we feel.

Listen to Nina Simone’s version of “Ain’t Got No / I Got Life”. It’s a mash-up of two songs whose sentiments couldn’t be more different, simplistic, and profound at the same time. She starts with a litany of things that are missing, things that are either gone forever or were never there in the first place: home, shoes, mother, culture, and God. She isn’t asking for a handout; she’s just letting us know about the emptiness but there’s no time for self-pity. Soon, she’s telling us what she has, what’s always been there: hair, head, brain, mouth, smile. Both songs are triumphant moments in the play, and Simone sings with triumph, not smugness. You may be down, but you need to remember what’s always been there:

There are fun songs in Hair, moments of love and happiness in such sentiments as “Good Morning Starshine”, simply a tribute to existence (“You twinkle above us / we twinkle below”). “Manchester England” didn’t seem to have much to do with the title city and country, but it did have a nice rhythmic rhyme scheme (“Claude Hooper Bukowski / who finds that it’s groovy to hide in the movies…I believe in God / and I believe that God believes in Claude / That’s me / That’s me”). It’s a strangely refreshing and almost remarkable moment in a song about a generation seeking refuge in random sexual and drug exploration. No matter what happened in their lives, they believed in God. However that belief took shape was irrelevant. The important thing here is that the belief was reciprocated.

Hair also offered some treats for the more literate-minded among its viewers, then and now. “The Rest is Silence”, a refrain in “The Flesh Failures / Let the Sunshine In”, was taken from Hamlet’s dying words and perfectly suited for this generation faced with a society faced with the consequences of sending their youngest adults to die in a useless international conflict. All that remains is just dust blowing away, and pieces scattered randomly on the tarmac will never regain their original form.

“What a Piece of Work is Man”, a quiet ballad whose lyrics are lifted directly (again) from Hamlet, might seem hopelessly precious and overly concerned with attaining academic respectability, but it works wonderfully within the context of the story. These are young people concerned with love, life, the future, and the status of humanity. What probably most struck the listener in 1967 as it should now is how Rado and Ragni brought an even deeper urgency to this observation of the human condition:

“How dare they try to end this beauty / How dare they try to end this beauty / Walking in space / we find the purpose of peace / the beauty of life / You can no longer hide / Our eyes are open (4X)/Wide wide wide”

How we see Hair today probably most likely depends on our allegiance to monuments of the past, tributes to dark matter perpetrated by our predecessors and elevated in the form of statues, Confederate memorials, and self-proclaimed “free speech” rallies. The bloody mess that was the Charlottesville, Virginia clash of white nationalist supremacists and counter-protesters in mid-August 2017 is but one incident in what will most likely get much worse before it gets better. The “supremacists” are militarized, enraged, and facilitated by forces in the highest echelons of the United States Government. More physical monuments will topple, flags will be re-fashioned, and tangible 21st century reminders of America’s collective bloody past might very well be relegated to museums, but the disease that has spread through the ruling class of this “dying nation” (a phrase from Hair‘s “The Flesh Failures”) can be traced to the White House.

Most college towns around the country are quiet in these last weeks before the start of the 2017-2018 semester, but the darkness is overwhelming. There will be more bloodshed, more sacrifices, and more innocent people dying for the cause. When history happens in the present tense as it has every day since the Inauguration of a petulant, vindictive, impulsive megalomaniac President whose presence has validated and implicitly endorsed this movement of hate, we can find refuge in productions (and films) such as Hair, which was as much a movement as it was a theatrical experience. Our eyes may be open, but we also need to take action.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)