Japan’s rapid modernization in the late 19th century triggered an existential crisis over what to do about folk beliefs, including deeply rooted beliefs about the spirit world. After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the country embarked on a rapid project of western-influenced modernization. The scientific rationalism that was much in vogue in the West dismissed such beliefs as superstition.

Two Japanese responses emerged – one that sought to ‘debunk’ folk beliefs as superstition and excise them from Japan’s new spirituality, a streamlined system of emperor-worship fashioned after the monotheisms of the West. The other side of what became opposing intellectual camps sought to collect and preserve folk beliefs as an important part of Japanese culture. It drew inspiration from European folklorists like the Brothers Grimm.

The former approach became the dominant one: emperor-worship emerged as the dominant state religion in early 20th century Japan and got tangled up in the country’s rising militaristic nationalism. When Japan was defeated in World War II, and emperor-worship formally abolished, the country was primed for a resurgence of interest in previously suppressed and ignored folk beliefs.

One of the country’s early folklorists was researcher and government functionary Kunio Yanagita. He treasured local folk beliefs, and his job gave him the opportunity to travel widely and collect them. He met a writer and storyteller named Kizen Sasaki, and in 1908 the two traveled to Sasaki’s home region of Tono in the northern Japanese mountains of Honshu. Visiting small villages and local festivals, Yanagita collected many of the area’s folk stories and published 119 of them in 1910 under the title Tono Monogatari (stories of Tono).

The survival of this book was a miracle in and of itself. A mere 350 copies were published; Yanagita gave many of them away himself. Like his passion for folklore, the book was not in vogue with Japan’s primary intellectual currents at the time, which were more interested in smothering local superstitions out of existence.

Nevertheless, the book survived and became a hit when it was rediscovered after the war. Yanagita adopted a literary approach to his work which was praised by the country’s new generation of post-war writers, including the Nobel Prize-winning Yukio Mishima.

It also greatly influenced rising manga star Shigeru Mizuki. He’d long harboured a passion for Japanese folklore – especially pertaining to yokai – and was a noted scholar on the subject, in addition to his award-winning comics work. He traveled to the Tono region, visiting the same places whose tales had infused Yanagita’s work a century earlier, and in 2010 – the centenary of the original – published a manga version of Yanagita’s masterpiece.

Mizuki died in 2015, but his manga has at long last made it into English translation (the original prose version of Yanagita’s Tono Monogatari was translated into English in 1975 by Ronald A. Morse). The English translation of Mizuki’s Tono Monogatari manga was undertaken by Zach Davisson, who, in addition to his own work in comics and translation, is also a renowned expert on yokai studies.

Yokai are at the heart of Tono Monogatari, but what are they? “Think of Japan as being covered by a layer of numinous, invisible energy,” writes Davisson in one of the many delightful and insightful mini-essays that pepper the book. This energy, by itself, is neither good nor bad. Certain sacred spaces, such as Shinto shrines but also natural locations, can channel and manifest this spiritual energy in the form of kami, which is often and inaccurately translated as ‘gods’.”

These kami, explains Davisson, can manifest a gentle side, but “this energy can also manifest in darker, more mischievous ways. Intense events, like sudden death or murder, or powerful emotions of love and hate, can give this energy physical form. These are yokai…They are bound by whatever task or emotion drives them. They are unworshipped and often dangerous.”

In his manga rendition of Tono Monogatari, Mizuki only presented his favourites from among those in the original. But the result is a hefty, absorbing read.

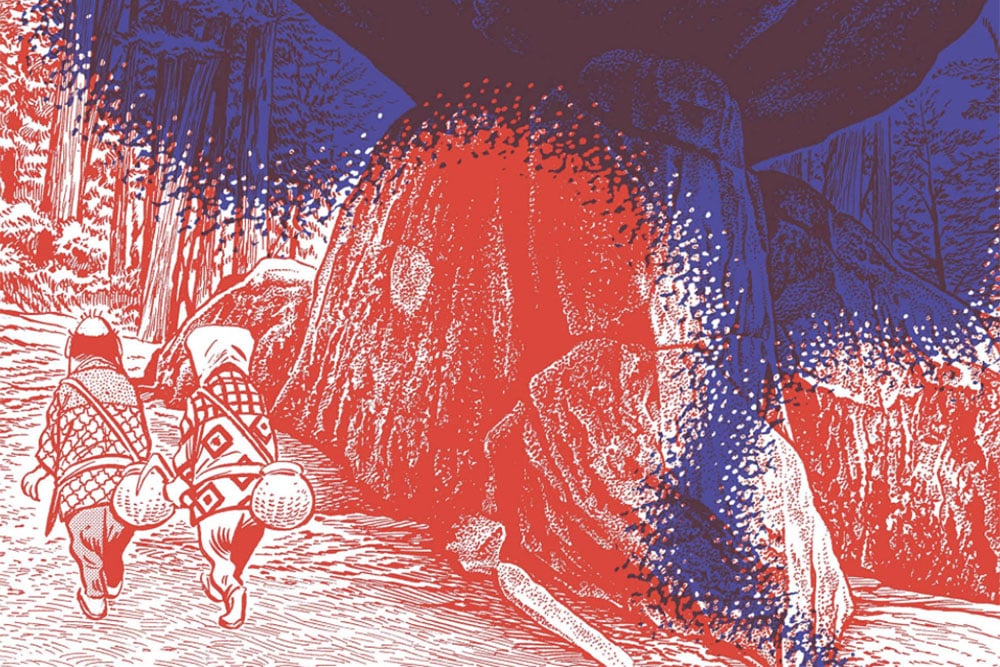

The stories are interesting as well as important in a folkloric way, although they’re mostly short, narratively simple tales. What makes the collection truly stunning and worth owning is Mizuki’s artwork, presented here in full, luscious effect. The rural, mountainous landscape of Tono is breathtakingly gorgeous, and presented from numerous vantage points across the various tales. Rice paddies, forested mountain valleys, traditional thatched huts – Mizuki’s eye for detail and his ability to render a scene in minutely detailed rendering is truly remarkable. His large landscape sketches – both urban and rural – have always been what draws me to his art, and here he gives full stage to his subject’s rural beauty. The book would be worth owning for the art alone.

Also of value is the supplementary detail provided by Davisson. Davisson has built a reputation as an expert on yokai in his own right – his growing body of work on the subject is well worth seeking out for anyone interested in the topic. Davisson provides a number of brief essays throughout the work, including a detailed historical introduction to the book. These reflections provide invaluable context for understanding the material and content presented in Mizuki’s art and narrative.

Publisher Drawn & Quarterly has been systematically translating and publishing Mizuki’s work, often for the first time in English. Tono Monogatari is a delightful addition to this oeuvre, an excellent companion read to Mizuki’s NonNonBa (D&Q English translation 2012), which draws from Mizuki’s childhood and relates the yokai stories told to him by his grandmother. Given the stylistic brevity of the original tales he drew on in Tono Monogatari, these stories lack the narrative depth and complexity that characterizes Mizuki’s original work. But they provide a rewarding and fascinating read nonetheless, and the brevity of the stories is more than made up for by the sumptuous artwork, which is every bit as satisfying as any of Mizuki’s texts. It’s another must-have Mizuki masterpiece, and readers will eagerly await future translations – hopefully in the works – of Mizuki’s splendid body of work.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)