You can say this much for certain about Sophia Coppola’s odd, enthralling, tedious, and frivolously sumptuous Marie Antoinette: it makes for a great trailer. The DVD release contains both the theatrical and teaser preview that dropped during the months leading up to the film’s hotly-anticipated release, but my concern here is with the latter. The three-minute regular trailer is mostly unremarkable, a fairly standard, and relatively listless, a montage of context-setting scenes and voiceover, the only injection of any excitement coming when a bit of the classical score is overrun by Gang of Four’s “Natural’s Not In It” (which song also serves as the intro music for the film itself).

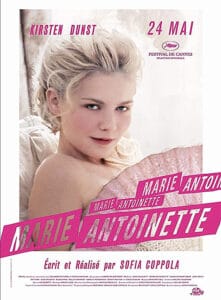

But the teaser trailer is in a whole league by itself. Buoyed up by New Order’s majestic and soaring “Age of Consent”, it is at once ebullient and wistful, liberating, and terribly lonely. We see Marie (Kirsten Dunst) giddy and ecstatic, running through fields and lying in the grass at early dawn with friends and champagne bottles; we see her bubbly and overflowing with laughter at her birthday party; we are seeing youth itself, unbridled adolescence bursting off the screen. But then we see her standing isolated and sadly contemplative on a balcony on the vast façade of Versailles as the camera pulls back, or collapsing in exhaustion on a divan, and we see her running desperately down a dark abandoned hallway as the trailer fades out. Towards what? Desolation? Tragedy? Salvation? Her face is impossible to read.

It’s also impossible to pinpoint the origins of this trailer’s magic, why it is just so overwhelming and exciting. It’s partly the choice of song, so apropos in both title and music; partly the way the scenes seem to give birth to each other in rapid succession, flowing naturally with internal dream logic; partly the lack of dialogue, anything that would break the spell; and it’s the way it seems to go straight through to the core of what the film will (or, should) feel like, without giving anything away about its substance. I know she’s only three films into what will most likely be a long and fruitful career, but I doubt Coppola will ever put together a more beautiful and perfect 90 seconds of film.

Then… Well, then of course you are seduced into watching Marie Antoinette in toto. For the first 20 seconds or so, it’s just what you hoped it would be: Marie lounging on a divan, dressed in her frilliest of frilly dresses, dipping her finger into the frosting of one of several elaborate cakes surrounding her, all the while getting a pedicure. She is staring off into nothingness, but then she slowly turns her head to us, looks straight at us, gives us an indulgent and knowing smile, holds it for a second, and then her gaze drifts back… Like the teaser trailer, it is just about perfect. Then… Well, then it all goes … well, not wrong, but not very right at all.

I’ve got to hand it to Coppola — very few films have ever left me so completely confounded, so completely at a loss for words, so completely grasping for an entry point, any way in at all, something hard and fast to grab onto and run with. Marie Antoinette– maddening, infuriating, evil seductress that it is — is such a film. Its veneer is so impregnably varnished, is buffed to such an imposing sheen, that any attempt at critical ingress either bounces off of or slides down its glossy façade. The film is much too deliberate and meticulously crafted to be a joke, a bit of nonsensical faux-historical fluff. Certainly it must all mean something, right? Something beyond an endless parade of gaudy dresses and indulgent desserts? But then, why do I have this nagging and persistent feeling that Coppola is putting us on?

But “confounding” is the right descriptive — any sort of qualitative assessment you lob at the film turns out to be both true and false, and thus lapses into irrelevance. What is Marie Antoinette getting at, beneath its period piece veneer? The excess of privilege run amok? Sure. The awkwardness and volubility of adolescence? Yup, that too. The banality of convention and custom? Why not? Isolation and loneliness, being everywhere a stranger, being adrift, bereft of home and family, wandering listlessly through a cavernous, sparkling purgatory? Now, maybe we might be onto something here, at last.

Coppola has made three films so far, and for the most part, excluding surface narratives, they are all pretty much about the same thing: just this sort of grand all-consuming adolescent loneliness, of being forever out of place and adrift, of being isolated and scrutinized, and forever in peril of being lost. Here we swap out Scarlett Johansson for Kirsten Dunst, and Tokyo hotels and karaoke bars for Versailles, but it’s the same purgatorial void we saw in Lost in Translation. Marie’s isolation is the more severe, though.

The daughter of the Austrian Empress, she is chosen in her early teens to marry the Dauphin of France, the boy who would eventually become Louis XVI with the passing of his grandfather. Wrested from her home, she is sent packing to a foreign court, surrounded by strangers with strange and strict customs, and even her new home itself is isolated from the rest of the world; Versailles standing isolated and removed from the rabble of bustling Paris, an insular, almost incestuous, island of royal splendor and excess. Immediately pressured to both produce an heir and smooth over relations between Austria and France, Marie finds herself incapable of effecting either. Her marriage remains oddly unconsummated for months, then years (the historical reasons vary — in the film the blame is entirely on the Louis); her position becomes precarious by her failure to produce a future heir; and she finds few friends among the cutthroat female denizens of the court.

So, what’s a girl to do? What’s the cure for all the sundry woes of our beleaguered Marie? Why, shoes! shoes! shoes! of course. And desserts! Lots of desserts! And champagne! Endless bottles of champagne!

Marie Antoinette only truly comes alive, fulfilling the promise of its trailer, twice in the film. The first comes just after Marie suffers a breakdown when another princess gives birth to a son, thus throwing her failures into glaring relief. Then we here the strident opening tribal beats of Bow Wow Wow’s “I Want Candy”, and we are treated to a rapid fire montage of Marie trying on frilly shoes, snacking on elaborate desserts, getting her hair done, playing cards, and drinking her cares away. Shoes and sweets, those time-honored palliatives for all that ails you, filling the emotional void with … well… stuff, lots of pretty and yummy stuff. It’s a great scene though, and slapped a big goofy grin across my face that was slow to fade, even as the film lapsed back into its tedium of court life.

Well, until a few moments later when Marie and company bounce off to a masked ball in Paris. Entering to what sounds like the opening strains of a waltz, the deceptive violins eventually reveal themselves to be the opening of Siouxsie and the Banshees’ “Hong Kong Garden”. Nothing totally disconcerting, as a well-chosen and effective early ’80s new wave soundtrack, punctuates the film throughout. But what you realize, quickly, is that this song is actually playing in the hall, that the ballgoers are actually dancing to this song, which won’t be recorded for another 200 years. This is no new trick, of course, but for some reason, it struck me as way more aesthetically pleasing and right than anything in Moulin Rouge. Again, it recalls the early promise of the film, that there was the potential for some genius here, some sort of temporal disruption and displacement, a confluence of the 1780s and 1980s, an imaginary but universal Versailles.

But again, the film lapses back into its period piece languor, never to recover in its tepid and tedious second half. Even as time accelerates, and we approach ever closer to the Revolution, history never seems to intrude. There’s mention of the American Revolution and France’s involvement; there are a few warnings of restlessness among the Parisians, but these cause barely a ripple in Marie’s cloistered world (which she later splits between Versailles and her pastoral country house). We all know this film caused howls of derision and contempt at last year’s Cannes, partly on the grounds of historical liberties taken and a lack of respect. Yet, it’s hard to see what the French go their dander up about. If anything, Marie Antoinette is defiantly ahistorical. This is a film of the interior; if not of the soul of its heroine, then at least what she chooses to surround herself with and is thus identified with, again, frilly clothes, shoes, and general decadence.

I realize I’ve gone from wondering if I even had enough words in me to write at length and coherently about Marie Antoinette, to finding plenty of ground to cover. But how well is it covered? Rather unevenly, much like this impossible film — anything I could say about it is equally right and wrong. I’m convinced that Marie Antoinette has absolutely nothing of value to say at all. And yet, since watching it, I cannot stop thinking about it. I don’t know whether this is a function of being lulled into submission by its riotous surfeit of outlandish pastels — an endless parade of soft pinks, baby blues, mint greens — or being hooked by its excellent and inviting soundtrack (Coppola seems only second to Tarantino and Scorcese in her soundtrack acumen). Perhaps it’s a persistent fascination with the Rococo excess of mid-18th-century court life that lingers in my mind. Or maybe it’s just that I’m missing something, something huge that’s right in front of me, which will eventually be revealed the more I ponder the film.

I want very much to believe that Coppola is getting at something more than we see on the screen. For all its faults, Marie Antoinette is a beautifully constructed film, and you’d hate to think it was all for naught, that such craft was all merely for show. Then again, that might be a perfect commentary on empty royal extravagance and splendor.

A paucity of extras “round out” the DVD release of Marie Antoinette. Aside from the two aforementioned trailers, there are two inconsequential deleted scenes, neither of which add anything of note to the discussion, nor extend beyond two minutes. “Feeble” best sums up the ill-advised stab at on-set humor that is a brief MTV Cribs tour around Versailles with Jason Schwartzman in his Louis XVI duds. And a 25-minute making-of/behind-the-scenes featurette illuminates exactly squat about the film — brief interviews with cast and crew only barely try to touch on the greater significance of the film beyond its sumptuous visual palette.

Indeed, the only point of interest is the interview with production designer K.K. Barnett, who talks a bit about the varying strategies for airing out the film of the sort of sepia-toned stuffiness which usually attends costume drama/period pieces. Would that someone had aired out the script, as well. Coppola, as enigmatic as her films, is typically reticent and camera-shy, which is fine — the film should speak for itself without any further explication from her. Too bad it has nothing to say.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)