It’s perhaps not surprising that the man known as ‘the god of manga’ should require a biography of biblical proportions. Clocking in at over 900 pages, The Osama Tezuka Story is a worthy tribute to the man who pioneered a great deal of the manga-anime industrial complex that today constitutes a multi-billion dollar global industry.

But Tezuka fought a pitched battle to keep his growing manga and anime companies a ‘creator’s collective’, rather than a commercial industry, argues his biographer Toshio Ban, who served as sub-chief of manga productions for Tezuka Productions, working under the manga god himself. That’s one of the over-arching themes of his tome of a biography; Tezuka’s relentless and at times ruthless work ethic is the other. The result is a book that provides an invaluable history of manga and anime development, but elides any true understanding of Tezuka the man.

The Osama Tezuka Story is a manga biography of the man who’s best known in the English-speaking world for works such as Astro Boy, Buddha, Phoenix, Adolf, Black Jack, Princess Knight, and many more titles in the more than 150,000 pages of manga (over 700 volumes) he drew during his career. Ban’s biography was originally serialized in an Asahi news magazine over three years following Tezuka’s death in 1989, and published in Japan in book format in 1992. It’s now available in English for the first time, translated by Tezuka’s fan, friend and translator Frederik L. Schodt, a manga and Japanese pop culture scholar himself.

The book collects an array of amusing anecdotes from Tezuka’s life. Copiously cited and referenced, the material is drawn from speeches, memoirs, and other commentary produced by Tezuka over the years for his Japanese audience. The anecdotes offer insight into many of the elements that he would later incorporate into his manga (for example, Astro-Boy’s irrepressible spiky hairstyle, inspired by his own struggles with unruly hair as a child). We see how his obsession with collecting butterflies fueled the obsession with metamorphosis that characterizes many of his comics. Other examples and inspirations abound.

The research is meticulous: the book opens by sharing some of Tezuka’s childhood stories and comics from grade school, and continues the pattern by inserting short and illustrative excerpts of many of his works throughout, from the internationally acclaimed to the whimsically personal and never-published. But these also reveal the very charmed childhood that Tezuka enjoyed.

In contrast to other manga and comics artists whose childhoods were troubled and marked by adults who sought to deter them from the graphic artist’s life, Tezuka, at least as he is presented here, received nothing but praise and support in his early years. His parents indulged his childhood artistic inclinations, providing him notebooks (even erasing his notebooks to supply him blank pages when the Second World War induced scarcity). They bought him comics at every opportunity, and his father had an extensive library of comics and other works to inspire the youthful Tezuka.

He was short and poor at athletics — classic fodder for bullying — but nonetheless his classmates idolized him for his artistic skills. Even his teachers encouraged him; by some fluke of fate or fortune he managed to avoid teachers indoctrinated by Japan’s militaristic nationalism and instead had teachers who praised his creativity and individuality, and encouraged him to continue writing stories and producing art, even when it affected his studies.

If Tezuka is considered a god of manga, he grew up in an environment remarkably conducive for such an aspiration. His story offers, perhaps, an example of what humans can accomplish when their childhood creative inclinations are nurtured with praise and respect, by peers and by adults alike.

Of course, this formative fortune was coupled with (if not generated by) a personal drive of tremendous energy. Tezuka went to medical school at the same time as he began getting contracts for his manga, and eventually found himself torn between the two fields. He persevered with his medical studies, passing his exams, but it was manga that won his heart, and to which he dedicated his life. This led to the incongruous phenomenon of a striving artist whose editors had to address him with the respect due a medical doctor.

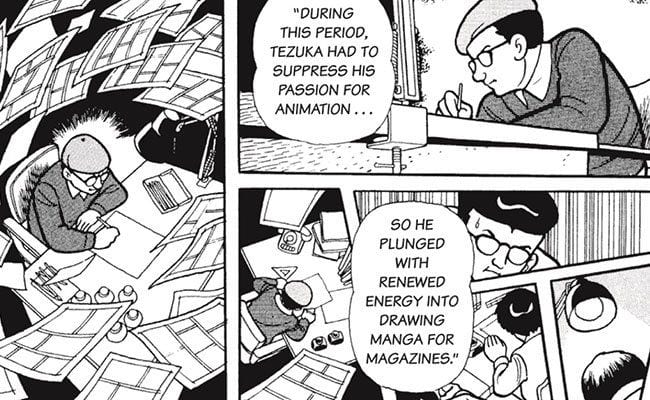

A striving artist, but not a starving one. Tezuka’s drive led him to win contracts with several of the top manga magazines just at the moment when manga was beginning to take off. The result was a grueling schedule of deadlines — his editors pursued him around town to make sure they got their comics, often crashing in his rooms as they supervised him — but no shortage of cash. Indeed, other manga artists began to resent Tezuka’s success, as he became known as one of the richest and most successful manga artists in the country.

A deeply ambitious man, his money-earning drive served a functional purpose: he was determined to earn enough to open his own animation studio. He was an obsessive fan of films — one year he set himself the goal of watching 365 films over the course of the year — and yearned to bring his manga to animated life. This he eventually did, pioneering many of the techniques and styles that would later fuel the anime industry.

Rich Details, Dry Story

While North American readers might open a cartoony manga expecting an entertaining story, what they’ll find here is actually a very technical and meticulously researched history. The book sheds a fascinating light on what life was like for manga artists in the early and formative years of the genre. It’s full of explanatory (and delightfully illustrated) asides on the technical production and evolution of manga, and offers unique sociological-historical vantages as well. For example, Tezuka had contracts with several different magazines, so each month his various editors would gather at a restaurant or bar and negotiate deadlines with each other. Tezuka himself would sometimes preside over the negotiations, rewarding his editors with sake when they reached mutually amicable agreements.

Still, they acted like his personal managers at times, locking him into hotel rooms rented by the magazines so he could finish his assignments undisturbed, or sleeping in his rooms and waking him to make sure he got their comics done by the agreed upon deadlines (these were common practices in the manga industry at the time, and were referred to in Japanese as kanzome, or ‘canning’). Sometimes he slipped away from them, and they had to scour the city in search of him (a common technique was to search hotel garbage bins for pencil shavings, a clear giveaway of a manga artist at work).

The field had its darker sides, too. Sometimes the grueling work schedules got the better of the artists, and burned them out or even killed them. The fate of Tezuka’s colleague Eiichi Fukui is an illustrative, if tragic, example. In 1954 the rising manga star died of karoshi — the Japanese term for death-through-overwork — just as he was entering his prime. Tezuka had crossed swords with Fukui, who was several years his senior, as described in Ryan Holmberg’s fascinating 2015 article in The Comics Journal. Tezuka may have regretted his critique of Fukui in the wake of his death, but his attacks on the senior artist illustrate both his own personal ambition, as well as a “crystal example of how manga’s new hero was no angel.”

It’s here that The Osama Tezuka Story leaves much to be desired. While incidents like Fukui’s death are referenced, and the less savoury moments of Tezuka’s career are alluded to, any sort of critical commentary on Tezuka’s life is strictly avoided. What’s more, the book avoids the sort of controversial material that would actually offer an interesting storyline. For example, Tezuka’s popular Black Jack series, whose protagonist is a rogue surgeon, often served as a critique of the Japanese medical establishment (with which Tezuka, as a medical doctor, had first-hand experience). Some issues tackled such controversial and sensitive topics — lobotomies, for instance — that the medical establishment successfully lobbied for their suppression (some issues were omitted from subsequent book collections as a result). As Cian O’Luanaigh recounted in The Guardian last year, this “scourge of the medical establishment… shaped the national debate about medical reform in Japan.” Now that’s the sort of thing that makes a biography interesting, but there’s little exploration of it here.

Perhaps some of this can be attributed to the fact that the 900+ page book was originally serialized (and immediately after his death, too, so the desire to eulogize probably trumped the desire for critical analysis). This probably accounts for the repetitive nature of the account: Tezuka has an idea; Tezuka faces a deadline; the staff overwork themselves and meet the deadline; everyone goes off to celebrate at a restaurant or a movie. In serialized format, it might have been more difficult to explore the more compelling, if controversial, side of Tezuka’s life and work. Yet Tezuka himself explored complex themes in serialization. Finding a way to do so would have injected a great deal more life into the narrative.

If manga straddles the divide between strong narrative plot and whimsical excess, it’s a tension that applies itself to Tezuka’s life in this telling. Tezuka comes across as a superhero; his steely gaze and jaunty beret belying an ambition of nearly superhuman strength. His portrayal in the book assumes all the dimensions of the comic superhero: he doesn’t sleep, produces record amounts of manga, looks after his assistants (who serve him happily despite his extreme demands), mediates between his editors, and tirelessly (almost effortlessly) redefines the genre after an idealistic image of his own ingenious devising. When he succumbs to leisure, it’s with equally ambitious results: he caps a four-day bout of sleepless manga-writing by taking his assistants out to the theatre with him.

There’s doubtless some truth to this depiction — his astonishing output is confirmation enough of his remarkable work ethic — but it leaves something wanting in the telling. The reader yearns for the human Tezuka, for some indication of his doubts, his setbacks, his fears and regrets (as it is, the only doubts portrayed in the story are whether he should pursue a career as a successful doctor or one as a successful manga artist, and he is already both by that point). Perhaps he had none of these human foibles, but the reader can’t help but be skeptical. Perhaps some day there will appear in manga form “Osama Tezuka: The Human Behind the Myth”.

Until then, Anglophones will have to be satisfied with the myth.

A Celebration of Creativity and Overwork

The Story of Osamu Tezuka is a magnificent tome of a book, an illustrated history covering not only the year-by-year life of Tezuka but the development of modern manga and anime. It’s chock-full with points of technical interest, and applies passionate devotion to the telling of Tezuka’s life.

So much so that it frequently goes overboard. It often becomes hagiographic, depicting Tezuka’s obsessive creative drive in heroic style. But this belies the dark side of obsession. The exploitation of his staff reached epic proportions — they referred to sessions in the early years of Mighty Atom’s (Astro Boy) animation as ‘death marches’, and when they later re-made the series he had sleeping bunks installed in the studio workspace — yet this is all rationalized as a pleasant byproduct of creative genius. The text quotes from Tezuka’s own account Boku wa Mangaka (I Am a Manga Artist): “In inverse proportion to the rising popularity of the show, the staff looked frighteningly emaciated. Some had nervous breakdowns, or fell ill and had to take time off… But most just gritted their teeth, and kept going. And the only thing that kept them going was pride in the fact that they were pioneering a new field…”

These scenes of overwork and exploitation appear repeatedly, framed as a celebration of creative devotion that’s hard to swallow in this day and age. In December 1966 an overworked employee of Tezuka who had devoted himself to the Atom TV show [The Mighty Atom, or Astro Boy] collapsed and died at his desk, and from the way this is presented it’s unclear whether the reader is expected to think this is a wonderful or terrible thing.

Certainly Tezuka achieved remarkable things, and can be credited with making manga and anime the successful fields they are today. He held the conviction that manga could become an international language, and surmount both cultural and political divides. He left a tremendous legacy (the vast majority of which has yet to be translated into English). But that’s all the more reason to treat his legacy with a greater degree of critical analysis. The Osama Tezuka Story goes into meticulous research and detail about the history of manga, but offers only the glowing surface veneer of Tezuka himself. The reader looking for an entertaining narrative will find instead a dry and clinical history, and a sense of inferiority if they can’t regularly operate on two hours of sleep a night.

One is tempted to compare it to Shigeru Mizuki’s autobiographical works — Showa, Nonnonba, etc. — but the difference is that Mizuki’s life was darn interesting. From his spirit explorations in the forest to his war experiences, Mizuki’s autobiographical work is deeply political, self-reflexively philosophical, and offers a riveting narrative. Tezuka’s story, by contrast, offers little more than a charmed life of obsessive, if creatively inspired, overwork. While the lover of Tezuka’s rich oeuvre, or the student of manga and anime, will find much to interest themselves here, let us hope that future biographies of the manga-anime pantheon — Hayao Miyazaki, Nanase Ohkawa, etc. — will offer a more critical, and human, portrayal of their subjects.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)