That Walt Whitman was born in 1819 has meant that many in 2019 have devoted considerable attention to the poet of democracy. The bicentennial has brought, for example, celebratory gatherings (Whitman@200: Where It All Began), a trio of museum exhibits (see “Walt Whitman: celebrating an extraordinary life in his bicentennial”, Julianne McShane, The Guardian, 12 June 2019) academic attention to neglected facets in his work “Whitman and Disability: An Introduction”, Don James McLaughlin and Clare Mullaney, Common-Place, Vol. 19 No. 1, Spring 2019), and an eloquent character portrait in The Atlantic (“Walt Whitman’s Guide to a Thriving Democracy“, Mark Edmundson, May 2019). But if this new Library of American release, Whitman Speaks: His Final Thoughts on Life, Writing, Spirituality, and the Promise of America, as Told to Horace Traubel, wings from the same momentous birth year, it roosts more snuggly in the poet’s aging and his death.

As the lengthy subtitle suggests, this volume selects from Whitman’s words as relayed in his twilight. For approximately four years leading up to his death in 1892, Whitman conversed with a young friend and confidant, Horace Traubel, who assiduously recorded the conversations for posterity. The five thousand words produced by Traubel eventually amounted to nine bursting volumes, all of which are now freely available at the online

Walt Whitman archive. The fact that readers have unlimited access to the whole smorgasbord of his work and yet will still find immense value in Whitman Speaks testifies to the wonderful work that editor Brenda Wineapple has accomplished in this carefully curated book.

As Wineapple explains in her excellent introduction, what Traubel’s material most needs is “compression” (xxiv). Albeit not a word usually associated with Whitman, such a concentration on “compression” is the right approach here. At least where non-specialists are concerned, unedited chronicles will drown the reader in excess and unevenness. Whitman’s discourse with Traubel is by turns profound, parochial, pedantic, and at times, downright boring. While

Whitman Speaks preserves flickers of all four such associations with his work, the volume as a whole is a powerful if abridged tour through the richly aged mind of a true American genius. Wineapple’s individual selections range from one sentence to several paragraphs and are presented cleanly on the page, without dates, citational information, or even Traubel’s contributions to the conversations. In roughly 200 pages, Whitman Speaks is readable in a single sitting or—thanks to its piecemeal quality—over a long and leisurely period.

Walt Whitman and his male nurse Fritzenger (By Dr. John Johnston, Bolton, England – Charles E. Feinberg, Public Domain, WikiMedia Commons)

After her insightful opening account of Whitman’s life and especially his relationship with Traubel, Wineapple packages the selections in a series of 35 thematic headings. “Nature”, “The Human Heart”, and “Writing” begin the book and, appropriately, we are eventually ushered toward the end with divisions like “Spirituality”, “Success”, and “Aging”. At times this logic of organization is perplexing. Some selections could appear under any number of headings, which makes Wineapple’s decisions seem arbitrary or simply unfocused. (A passage that discusses Abraham Lincoln, for example, is logged under “My Philosophy” (182) rather than in the seemingly more fitting section titled “Lincoln”.) Granted, these overlaps are to be expected and are even a testament to the organicism of Whitman’s thought as it weaves together, a quality celebrated more than once in Whitman Speaks. It’s not as if Whitman parsed his conversations with Traubel according to any categories whatsoever, let alone the ones that Wineapple has discerned.

And yet still the categories can irritate the reader. Circling around the same ideas renders some sections repetitive while others appear internally conflicted. Grouping all of Whitman’s thoughts on “Nature”, for instance, causes abstract sentiments to blur together as vaguely related renditions of some elusive coherence. Aggregating his statements regarding politicians, on the other hand, makes Whitman constantly disagree with himself (although yes, he contains multitudes and does contradict himself, as he relates in Leaves of Grass). Most frustrating was the editorial decision to completely decontextualize—to omit all references to year, page number, Traubel’s editions, and to the surrounding conversation. Perhaps all these excisions were necessary for the economy and craft desired, but at least this reader—admittedly, a sucker for footnotes—wanted more to grasp.

Category confusions notwithstanding, there is much to treasure here as Whitman’s personality rumbles through in its manifest fullness. He is optimistic and open-minded, always elated to see convention broken or refreshed. An outdoorsman in spirit even when not in body, he drove for the elemental forces—desire, growth, life—that spin planets on axes and keep lovers in orbit. He also trash-talks fellow writers and toots his own horn, at one point telling Traubel that “I have never praised myself where I would not if I had been somebody else” (86), a trippy sort of body-swap humblebrag. Nestled in a section Wineapple titles for “Self-Reflection”, this degree of self-centeredness is on brand. My personal favorite moment in Leaves of Grass sees Whitman hail his own pre-embryonic essence as being “transported” in the mouths of “monstrous sauroids.” (That’s “sauroids“, as in ancient lizards.)

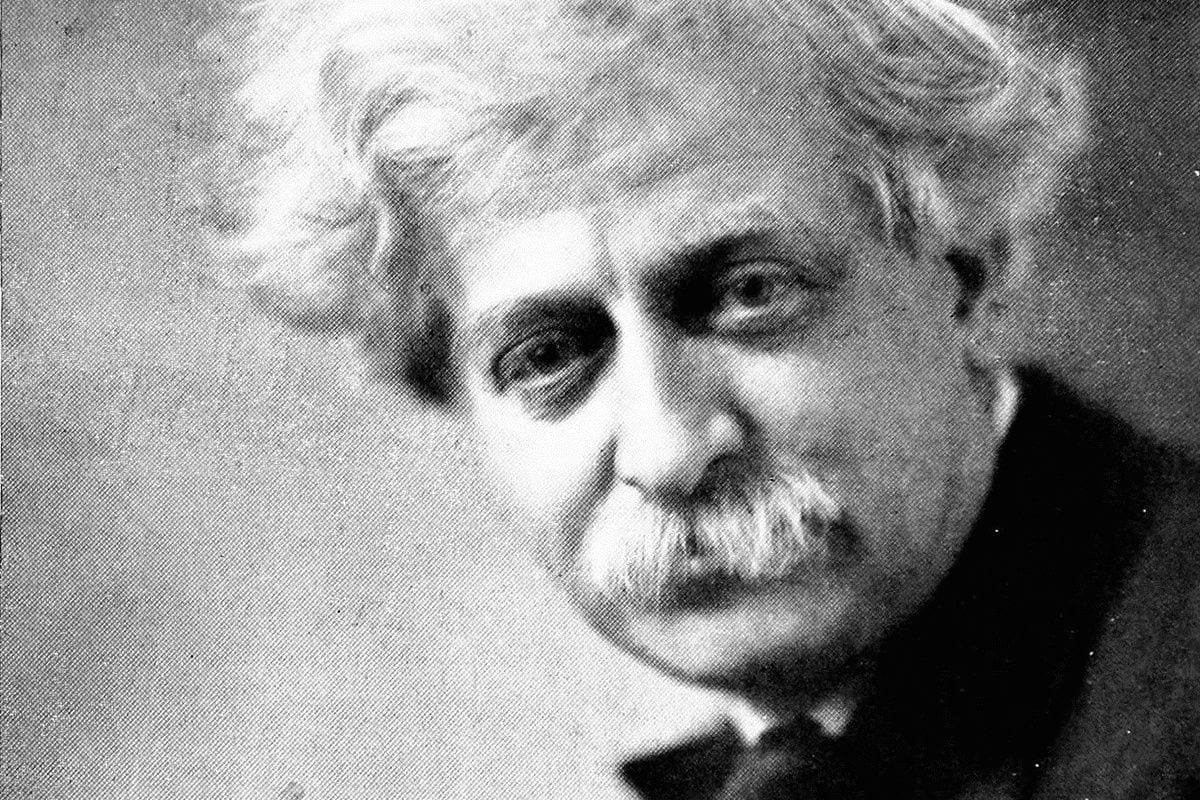

Horace Traubel, 31 Dec 1915 (Public Domain, WikiMedia Commons)

Even with Whitman often locating himself as central, however, the center of Whitman Speaks is undoubtedly the material comprising “Democracy” and “America”, sections that Wineapple smartly situates in the middle of the book. If Whitman’s birth affords opportunity to revisit his thoughts unto death, the year 2019 also assuredly prompts today’s readers to revisit the poet’s political and ethical commitments. To Wineapple’s credit, she does not dwell on the contemporary situation, preferring instead to let the selections set their own priorities. And the reader will be hard pressed to miss these priorities—or their timely relevance—when she or he comes across Whitman’s clarion call that “American must welcome all—Chinese, Irish, German, pauper or not, criminal or not—all, all, without exceptions: become an asylum for all who choose to come” (112).

There is no border fencing here; no essentialism bred from resentment. America, Whitman intones, is for the “average” person and the masses—for the “vast, surging, hopeful, army of workers” (113). As Whitman seemingly addressees our present while channeling the best of the past, he likewise proffers a future: “I look ahead seeing for America a bad day—a dark if not stormy day—in which this policy, this restriction, this attempt to draw a line against free speech, free printing, free assembly, will become a weapon of menace to our future” (114). A weapon of menace to our future: is this not an apt designation for the figure located at the vacuous center of America’s ongoing storm?

As Wineapple insists in her introduction, Whitman was full of faults that made him a complicated person in his time as well as a complex figure for readers to consider in these times. Any appreciation of Whitman at even his most democratic must confront, for example, the troubling commitments regarding race and section that he never resolved. In this particular volume, the most unsettling vein finds Whitman repeatedly pay homage to the Confederacy, a tendency that sounds, at moments, like insisting that there were “very fine people on both sides.” (“Trump Defends White-Nationalist Protesters: ‘Some Very Fine People on Both Sides'”, Rosie Gray, The Atlantic, 15 Aug 2017)

But rejecting reductive responses that would either pave over this tension or allow it to overrun our account, we would do well to listen in on what Wineapple has culled from what Traubel has preserved. Indeed, eschewing hero worship all together—a type of worship that Whitman, in his self-aware moments, would have rubbished—we are better off letting the poet speak for himself.

- In an Underground Bar With America's First Bohemians - PopMatters

- When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer: Gale Boetticher As Alternate ...

- Franklin Evans, or the Inebriate by Walt Whitman [ed. Christopher ...

- Walt Whitman

- American Experience: Walt Whitman - PopMatters

- Walt Whitman: and Brian Selznick: Live Oak, with Moss - PopMatters

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)