As the world slides deeper into recession, it might seem time to look to comics for escape. I find myself revisiting Andi Watson’s Breakfast After Noon, a book from 2001 that, rather than being a diversion, deals directly with job loss and the pain of economic restructuring.

“Breakfast after noon” is a phrase that easily conjures images of young, wealthy, 24-hour party people, however the title points to how the story’s male lead, Rob, reacts to losing his job at the local pottery plant, that is, with feelings of denial and depression. Breakfast After Noon is leavened with details about the changing nature of blue collar economies in post-industrial societies like the US and UK, but the strength of Watson’s book is found in how it addresses the psychic and emotional toll of unemployment.

Both Rob and his fiancé, Louise, are laid off from the Windsor Pottery plant. Louise immediately jumps to action, filling out the paperwork for unemployment benefits, and taking advantage of opportunities for education and retraining. By contrast, Rob can’t believe their jobs are gone for good. He believes that if he fights hard enough, he can get their jobs back.

Gradually, he learns that this is not the case, and he makes some attempt to follow Louise’s lead, but when he does finally avail himself of services at the local job center, he immediately looks for other jobs in pottery. While he waits for something to come up, he dodges questions about his and Louise’s future by dabbling in a phone card scam and other quick money fixes which might mask his lack of a paycheck but without implying that his job is lost forever.

Rob is shocked to learn that Louise does not share his desire to return to the pottery plant. One of the subtler insights to be gained from Watson’s comic is related to the gendered nature of industrial economies. For Rob, his job is inextricably linked to who is. He hopes that his desire to be back at Windsor will make it so, and he can only imagine that Louise wants the same thing.

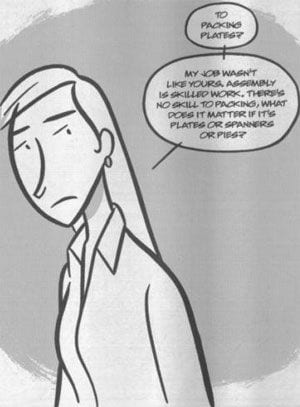

He learns differently after returning from an informative but fruitless meeting with his union rep. However, Louise sees being let go by Windsor as an opportunity to remake her life. Her job at the plant was nothing more than a way to make a living.

As she conveys to Rob, both through what she tells him and her look of pained skepticism, his work was always more meaningful than hers. Rob’s job is the kind of position that men in industrial economies held for generations. Like many men, Rob went from school to factory with the belief that he would be set for life. Women’s history in the industrial work force is not only more recent, but less stable, and more likely to be in peripheral occupations. For Louise, unemployment means the loss of income much more than it does the loss of self.

The question of expectations is central to Rob’s experience in Breakfast After Noon. One of the ways in which Rob expresses his denial about his job loss is in resisting changes to his consumption habits. He and Louise struggle over purchasing store brand potato chips. When he makes a little money from the phone card scam, he wants to use the cash for a night out, not for paying the bills. To cut back is to admit that the job is gone and that his comfortable, and comforting, world has changed. Wherever Rob goes in town, he is haunted by images of consumption.

While it is currently fashionable in the US to tut tut over the lack of savings and use of credit cards by individuals to buy beyond their means, one of the key differences between the current global recession-on-the-way-to-depression and the favored analogy of the 1930s is how much the American (and British) economies are driven by consumption. Access to goods and services like mobile phones, another point of contention between Rob and Louise, and comparable devices that decades ago were the province of the privileged few, are now available to a wider population. Easy moralizing about living simply, and fantasies about how people used to be poor, but happy, doesn’t alter how much of today’s shared culture is about consumption, or that the meaning of “providing” for oneself and one’s family is fundamentally different than it was when food, clothing, and shelter were the extent of one’s sense of the basics.

Rob grew up to believe that his job at the factory would afford him a decent life, one where he could afford some luxuries and time for leisure. Now, like so many working class men, he has to come to terms with the fact that life is not that simple, even if it may have been for those in the generations before him.

By contrast as a woman, Louise has not grown up with such expectations and, as a result, she has a sense of release from her layoff and a sense that she and Rob need to adapt to changing times to have the life they want. She’s willing to live with less, in part because she believes that the right choices will allow them to reclaim their standard of living. However, she knows that this requires action, not wishing life were as it was.

Regardless of where a reader finds oneself in relation to the current economy, Rob and Louise offer different ways to see or imagine one’s own reaction to economic hardship. They raise questions about what a job means and how we locate ourselves in the world according to what we do and what we buy. In losing their jobs, Rob and Louise are forced to respond to having their familiar coordinates of self taken away, but their experiences are still very different and individual, something that can be lost in the aggregate statistical measures that dominate discussions of economies.

Watson’s book also offers some notes of hope. As with many couples, Louise and Rob’s relationship is tested by economic hardship, but they survive, become apparently stronger, or at least more mature, than before. Louise finds a job in the new economy, working for a dot com, or, really, a dot co dot uk. For his part, Rob actually ends up with a pottery job again, albeit working for a different company in a different town, and “supervising” a robot that effectively replaces 65 people.

The truth and beauty in Watson’s work comes not just from Louise and Rob making it through and staying together, but also from the facts of Rob’s new job, facts that underline how much his world has changed despite his return to work in the ancient, albeit dramatically changed field of pottery.

His and Louise’s fictional experiences have and will be mirrored by countless others in the “real world”, now and in the near future. We can take heart that at least in this story, the couple finds some happiness despite hard times.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)