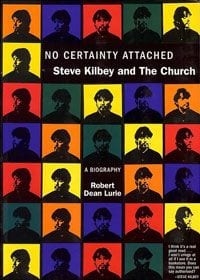

The adage is an old one, but accurate enough. Never meet your idols and heroes, because you’re bound to be disappointed. Robert Dean Lurie paid no mind. In 2003 he flew from his home in the US to Australia, to meet his idol Steve Kilbey. The fruit of his visit is No Certainty Attached,, an authorized biography made with Kilbey’s extensive participation.

But does Kilbey really qualify as an idol? Many critics and observers have opined that Morrissey is the last living true, great pop idol, a holdover and survivor from the days before the internet and quick shattered the traditional popstar myth and fractured popular culture’s attention span. Those critics have a point, but they’re forgetting Steve Kilbey.

Best known for “Under the Milky Way”, a song his band the Church recorded over 20 years ago, he’s simply not popular enough to be a pop idol. But for a relatively small group of people around the world, he is, and has been, a source of inspiration, fascination, and sometimes obsession. So, Steve Kilbey — the last living true, great cult hero.

Lurie’s task is a difficult one. No Certainty Attached is his attempt to crack Kilbey’s myth, lift the aura, and reveal Kilbey the man and artist. Many have taken this approach toward popular figures. However, Lurie aims to do it from the inside, by trusting his near-worship of Kilbey to lead him to a greater, more true understanding of the man, and by making this deeply personal journey part of the narrative itself. When Kilbey offers to participate in interviews only if Lurie can make it from the US to Australia, Lurie inhales hard and books a flight.

It’s a bold and dangerous move. In 2006, the accomplished modern fiction writer Douglas Coupland set off on a similar intercontinental journey to meet and interview Morrissey, of whom Coupland was admittedly a big fan if not a worshiper, for England’s Guardian. He couldn’t do it, deciding instead that Morrissey was “interview-proof… you could interview him for a thousand years and you’d learn nothing.”

Coupland instead offered some fleeting “impressions” of Morrissey. Lurie, however, takes it for granted that the book of Kilbey is still open. He decides to take Kilbey at his word, noting that Kilbey is not afraid to call him out for sounding too much like a “yes man”. The result, to the reader’s pleasure, is a surprisingly candid, humanistic, and often heartfelt portrait of a man who seems to be talented and troubled in equal measures.

Lurie devotes the first section on his book to chronicling Kilbey’s childhood, upbringing, and teenage years, through the formation of the Church in 1980. The similarities between Kilbey’s and Morrissey’s formative years are striking. Both grew up with a sense of isolation and dislocation resulting in large part from their emigrant families. Both took refuge in the dreamworld of pop music, developing a special fascination with the glam-rock scene of the 1970s, spearheaded by T-Rex and David Bowie. Both overcame, or overlooked, their relative lack of musical skill and formed bands. Both enjoyed immediate commercial success, becoming pop stars themselves.

Their discomfort with the attendant attention and publicity led them to make controversial and self-aggrandizing remarks to the music press, initiating long-term love-hate relationships. Lurie, however, draws no such parallels, putting all of his focus on Kilbey. But taking note of them provides some perspective. While Kilbey’s background may not have been typical, it certainly wasn’t unique.

The strongest, most touching part of No Certainty Attached deals with an aspect of Kilbey that Morrissey certainly does not share. Throughout the ’90s, Kilbey was addicted to heroin, though this largely remained disguised until Kilbey was arrested in 1999 in New York City for trying to buy the drug. While heroin addiction has become something of a rock’n’roll cliché, Lurie deals with it deftly, respectfully, and gracefully. He neither glamorizes nor sensationalizes Kilbey’s drug use. He recognizes the effect the drugs have on Kilbey’s creative process and the Church’s music, but doesn’t shy away from the ways in which it they intersect with his personal life, often with tragic results.

“Steve may have had a ferocious appetite for heroin,” Lurie writes, “but he always did his best to provide for his [young twin] daughters and shield them from his problem.” The statement would be funny were it not so poignant.

Eventually, Kilbey sells his earthly possessions to follow his daughters and their mother from Australia to Sweden. His addiction reaches its nadir on a wintry Swedish day that involves a drug score, a car crash, a broken arm, and black, decaying tissue. As Lurie and Kilbey relate the story, it’s not another tired tale of a fallen rock star but one of a tragic, struggling man and father. What Kilbey does not tell, and Lurie won’t reveal, is exactly why Kilbey decided to go cold turkey in 2000.

Unfortunately, Lurie does not bring this intimate, subjective perspective to his discussion of the Church’s music. While the band’s formative years, complete with ireful comments from jettisoned original drummer Nick Ward, make for good reading, Lurie’s track-by-track commentary on several of the band’s early albums does not. In one particularly lengthy discourse on 1983’s Séance, not one of the band’s major works, stock phrases like “lyrical stunner”, “exploring new terrain”, and “radical departure” flow freely.

There really isn’t enough trivia or insight as to the actual compositional and recording processes to satisfy die-hard fans, and casual readers will find their eyelids getting heavy. This is all the more frustrating because Lurie hurries through the band’s post-1995 output, almost universally recognized as the Church’s strongest, most intricate, and substantial work to date. Also, some of Kilbey’s many solo and side projects are given careful consideration, while others are ignored.

The most dicey aspect of Lurie’s narrative, however, is Lurie’s sometimes reckless insertion of himself into it. Obviously, the creation of No Certainty Attached was a deeply personal experience. To his credit, he’s up front about it, and asserts he has “endeavored to limit my own appearances to those directly related to Steve’s larger story”. It’s a commendable endeavor, but ultimately not a successful one.

On many occasions, the reader is getting Lurie’s story as well as Kilbey’s, not an intersection between the two. For example, upon meeting Kilbey’s brother John, Lurie confesses, “I wondered if I matched his expectations.” Lurie goes on to relate his “jealousy” at the close proximity in which the Kilbey brothers live. “But then I thought of my own brother,” he goes on, “and all the other places I had been lucky to call home.”

In some ways, this personal journey aspect is endearing. But in many others, it’s tough to see the relevance to Kilbey or the Church. Most troubling, and least professional, is Lurie’s decision to give what amounts to shout-outs to friends from various Church-related mailing lists and chat groups. These are simply too scattered and undeveloped to provide a serious insight into the nature of a cult following like Kilbey’s. Far more interesting are Lurie’s stories of how, between about 2002 and 2004, the Church’s very existence was largely supported by the technical and even financial efforts and donations of hard-core fans.

What sort of man drives a young American English instructor to teach that man’s novel to his high school classes in Georgia? Or inspires a wealthy British businessman to “pour thousands of dollars” into the man’s band? Lurie comes to his own conclusions. But, as Kilbey reveals and Lurie records throughout No Certainty Attached, and Kilbey evinces daily on his Time Being blog, a combination of disarming candidness and carefully-constructed enigma, coupled with genuine talent and a way with words, is a start. Lurie’s book isn’t a masterpiece, but it is a timely, fascinating portrait of one of the major Western (cult)ural figures of the last half-century.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)