“It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing”

– Duke Ellington, quoted by Chic; “Everybody Dance”

From the very beginning of its existence — which, of course, itself coincided with the birth of the teenager — a crucial function of rock ‘n’ roll has always been to get its fans through their adolescence. In my own time, this was true for me not once but twice — first via a two-year love affair with Metal, then through a profound and lengthy bromance with Frank Zappa.

Musically-speaking, Frank offered an alienated, self-regarding young man such as myself everything he could want. His stuff was oppositional, often impenetrable (at least by rock standards), and more to the point really weird. Better even than all that, though, was the intelligence sitting behind everything he did — something probably most obvious in the complete thematic consistency that ran throughout his work. (Something known in Zappa-land as ‘conceptual continuity’.)

While Frank’s intellectualism suited me at the time, there’s something about the ways it often came out that, as a grown-up, I have a problem with, such as how aggressive — didactic, even — he invariably was in voicing his opinions. (Or to put it another way, echoing Naked Lunch, he seemingly had an answer for everything, from the correct underwear to how to wipe your ass.) Another, and probably more important factor, was how mealy-mouthed some of those opinions were, invariably about stuff that was in reality fairly innocuous.

One particular thing (alongside Grateful Dead Fans and the ‘60s) that had a special circle reserved for it in the Inferno was disco; his attitude toward which was best expressed in two songs dating from the mid-to-late ‘70s. The first, “Disco Boy”, is a Mogadonlike slow rock stomp in which a patron of la discotheque resolutely fails to get laid. “Dancin’ Fool” tells the same story, but with the hero crashing and burning because of his two left feet.

To those that know a bit about Zappa’s worldview, his reasons for disliking disco will come as no surprise. First off, there was the environment itself, which he considered to be an exemplar of an increasingly decadent, standardised popular culture. As he said in an interview with Down Beat in 1978: “Disco entertainment centers [i.e., dance clubs] make it possible for mellow, laid-back, boring kinds of people to meet each other and reproduce. People who think of themselves as young moderns, upwardly mobile, go for fusion or disco.”

Then there was the way disco’s foolish young consumers had debased music itself by allowing it to be co-opted into a pre-packaged, hyper-marketed, ‘lifestyle’. This was apparently seen by Zappa as a betrayal of any number of things, from the correct, top-down listener/composer relationship, to rock’s eternal obligation to stick-it-to-The-Man. (It was also something that inadvertently aligned him with radio personality Steve Dahl’s “Disco Sucks” yahoos, whose nadir came during Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park in 1979).

Lastly, however was the music itself, which for the most part Zappa simply thought was below him — easy to make, but ultimately too constricting to be artistically worthwhile. As he suggested during another interview (this time on the Frank Zappa Interview Picture Disc), the last thing the ‘disco consumer’ wants is variation, not in the production, and certainly not rhythmically.

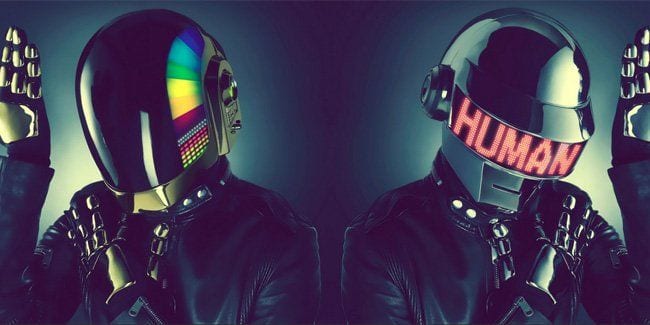

More than 30 years on from “Dancin’ Fool”, the negative discourses fostered around disco persist. If original criticism centered around ‘authenticity’, however, the suggestion now is that disco is an anachronism — something evidenced recently by reactions to Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories.

Appearing earlier this year, Random Access Memories was met with massive public interest, generated in large part by the pre-album release of its first single, “Get Lucky”. Much of this fuss had to do with the fact that the song was — not to put too fine a point on it — an 80-proof, dyed-in-the-wool, 24 carat banger. Even more important, though, was the question it raised around its own production. Was the whole album really going to sound like some kind of evil cyborg Chic clone? Hang on a minute… isn’t that Nile Rodgers?

The tease continued right up to the album proper, with interviews revealing not only that the duo were recording with analogue equipment, but they’d come to regard computer music as ‘sterile’. Clearly, for a band that plays Black Sabbath to modern EDM’s heavy metal, this seemed counter-intuitive, to say the least. More was to come, though — yes, it was Nile Rodgers; and here’s Giorgio Moroder, Paul Williams and a bunch of very expensive session musicians, as well.

When it finally was released, critical reaction to Random Access Memories was generally positive, and rightly so. There was a minority, however, that just hated it. Such feelings apparently stemmed from the way many felt that the androids had lost touch with the dance music zeitgeist. There was even a sense, of push-back by the EDM community following the duo’s comments about electronic dance music’s current ‘identity crisis’.

Predictably, the majority of the criticism centered on how – perhaps ironically – “old-fashioned” the record sounded. This was a feeling best, and definitely most amusingly, summed up by Diplo, who initially compared the music to Pete Drake and his legendary “singing steel guitar”. Music journalist Alex Macpherson, quoted during a Twitter mini-shitstorm following a leak of the album said, “Listening to a certain new album; feel like I’m listening to classic rock for old men. Really bored. Dance music reaching its Mojo point.”

Given disco’s apparent “plasticity” (Zappa), one irony fluttering around Random Access Memories is the way that it taps into the old discourses of authenticity, but in a dance music context. For example, whatever the aesthetic purpose of the record’s guest appearances, there’s a definite sense that dues are being paid. The use of analogue equipment, meanwhile, as stated by the duo themselves, is an attempt to imbue the work with a ‘timeless’ quality.

Beyond questions of mere old skoolness however, there’s also an even more profound examination of the authentic going on here — something squarely located in the album’s ’s re-conceptualisation of good music as music with a ‘purpose’.

Going back to Zappa, one thing he did not think was silly was 20th century avant garde composition; music which, unlike disco, was both challenging and clearly the product of driven, individual Genius. As any Frankophile will tell you, Zappa had immersed himself in this stuff from childhood, particularly following his early exposure to the work of Edgard Varese. He subsequently made it his life’s true task, emulating his heroes by incorporating experimentation into everything he did.

Modern as Zappa considered himself to be, however, one thing he absolutely was not was ‘utopian’, a trope of Modernity requiring both a cynicism-check, and the making of art that was something other than just ‘pretty’. (Aesthetically-speaking, I would put Zappa in the proudly impenetrable tradition of high modernism, at least in terms of aspiration. Politically, however, his work reflected a rather acidic take on Swiss Dada, a movement that profoundly influenced both his live shows and cover art.)

With that in mind, it occurs that there may have been one last thing that Zappa had against disco — that is, its idealistic, almost utopian sense of community. That the very existence of something as utilitarian as the dancefloor represented a capitulation, to both capitalism and to the stupidity engendered by it.

If disco does indeed possess a genuinely utopian impulse — if it really does play the sexy Constructivist to Zappa’s Dada — this is something Random Access Memories exploits to the full. In fact, you could argue that given some of its themes, it’s as Modern as it is post-modern. And by extension, far from betraying the spirit of dance music, it actually embodies it.

The album begins with two tracks whose sentiment is so simplistic you might wonder why they bothered writing the lyrics at all. The first is “Give Life Back to Music”, another Nile Rodgers-co-penned thumper, which provides the first of the album’s many exhortations to dance — “Let the music in tonight/Just turn on the music/Let the music of your life/Give life back to music.” Next up is “The Game of Love”, a lament for an elusive lover which, like “Give Life Back to Music” repeats its lyrics like a mantra, this time over a plaintive, gorgeous, disco shuffle.

These songs provide the most elegant of introductions to the album, not just in terms of its themes, but also its purpose. The music here is to be listened to, of course — why would they have spent all that money if not? More than that though, it’s to be used — to move to; as a soundtrack to a night out; to cry along with. These are the fundamentals of what rock ‘n’ roll is actually for. That’s why these songs take up so little space on the lyric sheet; this is the essence, boiled down.

Things get even more interesting with “Giorgio by Moroder”, a spoken-word piece in which the disco super producer tells his own story over a free-wheeling, protean backing track. Still striking in its audacity now, this homage to one of the ‘teachers’ is central to an album which, as discussed, hinges on notions of authenticity. More than that though, it also marks Random Access Memories’‘s most obvious use of explicitly Modern tropes — first in the track’s focus on technology, and then in the way its form is dictated by its function.

“Georgio by Moroder” begins with Moroder describing his early career, particularly attempts to forge the “sound of the future” using synthesisers — something which would reach full fruition in his epochal work with Donna Summer. Once his working method has been established, the subject moves onto his artistic philosophy; in particular his equation of music with freedom, and the role of machines in achieving that freedom. (Or to quote the man himself: “Once you free your mind about a concept of harmony and of music being correct, you can do whatever you want.”)

So far, you might say, so Mojo. But there’s something fiendishly clever going on too, the music morphs to reflect Moroder’s story as he tells it, from proto-disco to Omar Hakim-driven space rock. When I first heard “Georgio by Moroder” I thought of Oxen of the Sun, the episode in Ulysses in which style continually changes to mirror the historical gestation of the English language. For the purposes of this piece though, a more apt touchstone is probably the Bauhaus, with its faith in finding genuine common ground between art and functionality.

The move from the abstract to the ‘concrete’ — from listening to living — is finally codified on the album’s aptly-named centrepiece: “Touch”. The song begins with the record’s most post-modern moment, via a spoken intro from Paul Williams, referencing his own work in Phantom of the Paradise. From there, like “Giorgio by Moroder”, it blossoms into an eight-minute uber-track. This time, however, the touchstone is not disco but brass and piano-driven easy listening.

Anyone familiar with De Palma’s movie will likely pick up on the subtext of the intro straight away. Like that film’s central character, the song’s android narrator is desperate to locate his own humanity behind the mask. Unlike the Phantom however, the humanity in question has not been lost (in a freak record-pressing accident), so much as it was never located to begin with.

As with the angels in Wim Wenders Wings of Desire, here we find the robots pleading to be able to connect with flesh and with feeling. To leave the realm of ideas and enter into a lived relation with the world — with other beings, but also with the life music that they themselves have created. “Touch, sweet touch/You’ve given me too much to feel/Sweet touch/You’ve almost convinced me I’m real”

If “Touch” is the moment where the album shows its (human) hand, it’s also, ironically, where any analogy between disco and Modernism has to break down. After all, little in 20th century utopian art, from Le Corbusier to Speer, was concerned with actual, flesh-and-blood human beings. At the same time, conversely, disco is all too human — overwhelmingly pleasure-seeking, and, as Uncle Frank would tell you, completely driven by the market. It sets out to ‘perfect’ nothing except the groove; which it does, brilliantly well.

While disco may not exactly mirror Modernism however, Random Access Memories is still a thoroughly Modern text, if only because it does so many new things. It shows us, for example, how retro influences can be spectacularly re-incorporated, unencumbered by either irony, or authenticity for its own sake. (Something articulated on the album via “Fragments of Time”’s series of endlessly ‘shining’ moments).

More than that though, it confronts traditional definitions of taste and Culture — not by dissolving barriers, but by turning them inside out. It triumphantly elevates disco — and easy, and fusion — for the simple reason that, canon or not, people love this music. It kicks self-referential, purely ‘representative’ art temporarily into touch, paying homage instead to the simply useful. Best of all, it orders spurious, ill-defined discourses about “proper music” to sit quiet, letting the human beings alone to lose themselves to dance.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)