I. Dapper LeChampagne disintegrated into a moment of love at the Band of Horses show. Three days earlier Dapper had been speeding on Highway 360 into town. The sky looks bigger out there, out where parents pull over on the side of the freeway to take pictures of their children playing in the bluebonnets. The clouds pillowed over the giant blue expanse, looking a lot like the time he’d first driven into Texas and had to turn on the radio just to make sure the cumulus formation he saw wasn’t the end result of a nuclear bomb. He sighed at the sight of the city’s skyline up north. He’d only recently begun to notice the smog that hazed over Austin like yellow on a smoker’s teeth. It made him feel extra hot and he stretched his arm out to catch air. This was the third year he’d called this state’s capital his home. He knew how to avoid the commuters and drug traffickers at a stand still on Interstate 35. He knew to avoid the one ways that snare the blocks from the capital to the bridge from exactly 4:45 pm until 6:15 pm. He knew where to park on Red River. But this was the first year he’d felt it: That slithering malignant mass that creeps around the psyches of even the best intentioned hipsters moving to a land known for its cool. Entitlement. Three days of music and out-of-towners has a way of seeming like a chore in a place known only to itself as the Live Music Capital of the World. He caught himself quickly in the negative headspace and pulled into a free meter space instead. He gave his quick prayer of thanksgiving to the gods that always seem to find him parking, opened his door, and saw a penny on the ground. A shiny ’08. Heads up. Lucky! He almost gave it to a crack addict outside of Emo’s. He was waiting in line for the pre-ACL free show. A stranger was listening to him explain the similarity between the desire to leave the line before getting in and leaving a bus stop before it arrives. A woman with missing teeth and Brillo pad hair approached wearing a stained tank top that loosely outlined her sagging breasts. Her eyes were huge like headlights must seem to a deer standing in them. “C’mon man, got some change?” she said. A guy behind him with sun glasses hanging on a croakie said, “No. Never. I’ll never have money for you or anyone like you.” Dapper reached into his pockets and all he felt was the penny. He thought maybe he could explain it to her. It was all he had but he found it heads up. It was lucky. But the woman jerking through the crowd looked desperate like a child might if someone had taken her imagination. She needed more than a lucky penny. The bouncer motioned the next four in and Dapper felt like a bus had shown up. The capacity crowd squirmed from the outside stage to the front room and back out again, spilling Lone Star on each other apologetically. Despite its size, Emo’s has a way of feeling like a house party with some bands in the background. Dapper squeezed through the doors towards the back of the club. He found some standing room in the center of the crowd. A girl next to him pinched the ass of the guy in front of him. The guy frowned back at Dapper with a “Lucy you got some splainin’ to do” kind of look. At that moment, though, the banjo player from the White Ghost Shivers stepped on the stage for their quick sound check. He was a wiry, seven and a half feet tall. Dapper had once seen him at a party off South Congress. There were stilt walkers at that party which really seemed to emphasize the guy’s height because his head was at the same level as theirs. He must attract a crowd wherever he goes, and here the crowd was waiting to see him. Emo’s turned loud as he and the rest of the Shivers took the stage. They came out rollicking and roaring through a set of old time southern-swing that had a few couples in the back attempting a Lindy Hop. Dapper was thinking his Grandmother might have dug this music until the slick backed guitar player from South Carolina led his audience in a rebel yell of Fuck! and Fight! followed by a hootenanny sing-a-long of cocaine, gonna kill my baby dead. This was old folks’ music for the young, and the Shivers played it like actors on a murder mystery train ride. The stilt tall front man wore a giant fake moustache, the guitar player looked like Glen Miller, and the Betty Boop singer had a giant feather in her hat that almost touched the ceiling. Dapper knew her from his gym where she worked. They had a “how you doin’” kind of relationship. He almost hadn’t recognized her all dolled up playing the slide whistle and singing about doing it down south.

After the show, Dapper walked the six blocks back to his car. A man called to him from across the street. “Hey! Hey!” The man ran to Dapper. He was well dressed for a guy hanging out near the shelter. He wore an earring and was already beginning a speech familiar on Red River. “Aw, man, I’m an evacuee,” the man said. “I swear to you, man, I swear, I just got up here, I got a wife, I got kids. They all back in Houston. Man I just gotta get this bus, see. You know I ain’t messin’ with you. I ain’t like those guys on sixth. The bus ain’t come. I got this bus card. Bus ain’t been comin’ for like an hour. I just need some bills, man, you got some bills?” Dapper reached into his pocket. “All I’ve got is this penny,” he said. “Aw, c’mon! You know a penny ain’t gonna do shit, how you tryin’ to play me?” “Really, it’s all I’ve got,” Dapper said. He gave it to the guy. “I found it heads up. It’s lucky.” The evacuee took the penny. “I tell you a story,” he said. “You seen that movie Old Country for No Men? Man that’s a damn good movie. Here, you know this part: Call it. C’mon, call it!” The man held the penny out like he was going to flip it. “Doesn’t the guy kill him after he flips the coin? I’m not sure I want to play this game,” Dapper said. “Oh man, it’s a good scene. C’mon call it!” “What are you gonna do when you flip it? Are you gonna kill me?” “What you think just because I’m an evacuee down here at the shelter I’m gonna kill ya?” “Isn’t that what happens in the movie?” “Man … Oh, SHIT! That’s the number 20!” A bus was turning the corner and approaching the stop across the street. The man clutched the penny and ran to catch it. Dapper walked to his car. There was a quarter on the ground. An ’08, heads up.

II.

The three day Austin City Limits music festival blankets Zilker Park like a Wizard of Oz fantasy. The sites look familiar, but everything feels upside down. It’s hard to picture Town Lake’s trail outlining the grounds and the river just behind the stages. Inside ACL, Austin’s city limits seem restricted to the edges of the speakers and the skyline backdropping the stage called AT&T. Dapper found a spot in the crowd in front of a smaller tent stage.

“WaMu isn’t even a bank anymore,” said the woman next to him. She was older than him by a decade at least, thin, with a friendly but tired face. Dapper thought she was pretty and that her cowboy hat made her look a little wild the way Texas women can be. She was referring to the corporation that had sponsored this smaller stage.

“They’ve been around for a hundred years,” she said. “They just got bought out by JP Morgan last night.”

“They better change the name of the tent,” Dapper said.

“Guys in masks’ll show up. Spray paint ‘JP Morgan’ all over everything,” the woman said.

“Then the army, they’ll come put ‘United States’ over that,” said Dapper.

She pulled out her phone to write a text to her friend.

“China will put their name over that. Damn, I sent a text a half hour ago. It’s like all the texts are blocked.”

“Unless you’ve got AT&T.”

She looked him and shrugged.

“Things are so fucked up. I’m just here to listen to some music. What else can we do? This is going to be loud!”

Say the money just ain’t what it used to be …

A cheer rose as an unassuming guy in a baseball cap walked onto the stage. He mouthed “who is this guy”, pointing to the radio announcer MC giving him an unnecessarily adorned introduction. Most of the folks in the WaMu/JP Morgan/USA/China tent probably knew M. Ward already. Dapper did not know, though, that the songwriter had those kinds of chops. Standing on the stage by himself, M. Ward pounded out a rhythm line with his thumb on the low E while the rest of his open palm picked chords with the same expressive intonation that his voice manages. His extended fingers and heavy accents hinted at the kind of self taught virtuosity associated with the ghosts of bluesmen past. And there were the words.

I know when everything feels wrong,

I’ve got some hard, hard proof in this song.

He could have held the stage by himself.

I’ll know when everything feels right,

Some lucky night.

But it was when the band came out, the man and woman taking respective thrones on two kits, pounding the beat like yin and yang timekeepers each playing a part of the whole, their hits sounding so complete, the Rhodes player, the rhythm guitar, the bass. The harmonies. It was when the band came out that M. Ward’s songs began exploding like punches to the chest. It was when the band came out that Dapper began his unraveling.

She said, “If love is a poison cup, then drink it up.

‘Cos a sip or a spoonful won’t do, won’t do nothin’ for you,

Except mess you up.”

As the songs began soaring into the ethereality of pop music, Dapper’s body began to move.

Well he stomped with his feet and he clapped with his hands,

He summoned all of his joy when he laughed.

He sang! He moved

He put his trust in a higher power,

He held his power like a holy grail.

He felt his heart beating with the two kicks on the stage and wondered if, when it stopped one day, people would say,

He was a good man but now he’s gone.

He wondered how so many in this crowd could witness the miracles drifting from the stacks in front of them and stand there so still and withdrawn. It was the curse of Austin that it took more than a day to unravel the Entitlement. But people were swaying, the arms were unfolding, the smiles were beginning to crack the frozen faces as those cloud-lurking Beach Boy harmonies blew through the hipster apathy like a specter,

Now you see her now you don’t,

You think you’re gonna get to know her

Dapper felt the choke of watery eyes as the singer crowed,

I hope my little brother puts a call in today,

I hope he don’t forget where he came from,

‘Cause I lived with many ghosts when I was younger.

Dapper could have written the same. And he and the woman both so helpless at the collapse of their country’s economy happening around them

Hoping that my mind won’t slip,

Sailing on a sinking ship

raised their arms in celebratory agreement that

God it’s great to be alive!

as M. Ward left the show channeling the voice of Austin’s mad ambassador Daniel Johnston.

Dapper floated from the tent. The low end rumblings and occasional vocal echoes from each corner of the park emphasized the feeling of groundlessness. There is something almost hallucinogenic about the sound of bands pulsing from every direction with no aural focal point and Dapper wandered through the disorientation as if he were listening to a hidden 3-D image, waiting for his ears to focus. Mates of State hooked him in with a couple of bouncy pop tunes and a string section. Hot Chip sounded exactly like they do on CD, and somehow the subtle catch of their mellow inflected dance tracks still felt subtle on stage. Their glasses and jump suit wearing shtick might have worked better in a dark club than on a Friday afternoon. Someone in the crowd said, “these guys are dorks!” Dapper cut out early.

He made his way to the big stage. The crowd there was trickling in and waiting. He sat on a couple’s blanket near the front.

“Are y’all as excited about this as I am?”

The girl smiled like she’d just seen an old friend.

“I’ve been waiting for this show for weeks. I came from Lubbock just to see Him.”

She pointed at the stage. She wore thick glasses and low hanging skater shorts like a teenage boy might wear. Her boyfriend was missing a couple of front teeth and wore a sleeveless t-shirt that showed off the anarchist “A” sliced into his shoulder. He grinned at Dapper but didn’t respond.

“I read His blog all the time,” the girl continued. “He’s hysterical. Well, I don’t know if He’s funny, you know, he’s just Him.”

“You’re from Lubbock?” Dapper asked.

“Yeah,” she said. “It’s in West Texas. We’ve got a lot of great songwriters. It’d be a cooler town if everyone there didn’t end up moving to Austin.”

The quiet anarchist nodded and muttered something about dropping acid for the show. The girl stood up.

“Hey, these people better not crowd in here. We’ve been waiting for an hour.”

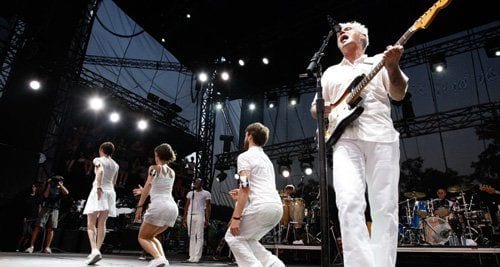

There was a collective push towards the front. The size of the audience seemed to swell instantly. A roar made its way to the back like a wave as an all white clad David Byrne swaggered to the microphone. The color of his hair matched his outfit. It made him look like an old man but his face looked Photoshopped from 1984’s Stop Making Sense. And his voice had aged even better than a cliché about wine.

The music pulsed over Dapper the way blood moves. Byrne sang, “This groove is out of fashion, these beats are twenty years old.” But the familiar steady kick-snare dance beat that kept a generation of coked up yuppies dancing sloppy in their urban lofts still worked for Byrne’s new Brian Eno collaborations the same way they did when his rhythm section consisted of a clockwork married couple. Hyper-flex dancers in white twisted around behind the man on stage, looking like nurses from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in their really wild off hours. Dapper felt his body pumping with the heart from the speakers and still, the crowd stood still. What is this place? Dapper thought to himself. Who are these people? Can’t you hear it? Water dissolving!

As the set evolved into choreographed chair dancing, frog leaping, and Talking Heads, Talking Heads, and more Talking Heads, Dapper felt the sound washing him down, washing him down. “No need to worry!” he shouted. “Everything’s under control!” And the ice caps in the north began to melt under the heat of the sun, and the financial institutions began to crumble, and the stand offs in the places far away began to stand on again and the cold, cold faces of a hot crowd in Austin began to warm and bodies were moving! He was floating above it and he was joining the world of missing persons and he was missing enough to feel alright. He felt a hand tapping him in the thigh and he turned to see the pretty girl from Lubbock and the quiet anarchist dancing like osprey on the water. They all moved their heads like beaks and stamped at the ground together. Some things sure can sweep him off his feet, Dapper thought to himself.

He swam out of the gates onto Barton Springs road where street vendors selling tie-dyes and marijuana pipes had turned up the speakers. The Jackson Five were singing “she’s a dancing machine” and the dreadlocked sales people were all bouncing like pixies. A large Earth mama wearing a skirt and a One Love t-shirt and a head wrap danced up to Dapper holding a stick of incense and they broke it down between the tapestries and posters. She twirling her enormous hips and him gyrating moving, grooving, dancing to the music. He moved from tent to tent like this and at the end was a marimba band, four giant xylophones and a drum kit and a crowd moving like a One Love t-shirt outside the festival. The people were moving!

The dancing was beginning!

The disintegrating was integrating.

III.

A guy came up to Dapper dancing wildly. He was high on psychedelics.

“I’ll be at the kiddie stage later,” the guy said. “I’m getting a drum circle started. It’s gonna kick ass! You should come.”

Dapper wished him luck.

It was beginning to get hot early on the festival’s second day. Any time under a tent at ACL is restorative, even before the heat begins sucking sweat from pores like a dehydrating vampire. Dapper ducked into the WaMu stage as The Lee Boys were chanting “I can feel the music” over bottom heavy funk made dirty by a pedal steel guitar. Dapper felt it too and began shaking his body with each gut thumping guttural call from the seven string bass getting pounded by a slap happy big man on the stage. They were all big men. The veteran guitar player, the vocalist yelling “Praise You God,” and most of all, the drummer they called the Big Easy, all bigger than life singing hallelujah songs to the WaMu tent revival.

“We’re a big family, we’re all a big family here,” yelled the guitar player. The crowd cheered. “Collared greens, fried chicken, we need us a family dinner.” The crowd agreed. The vocalist chimed in, “and family supports it self. They buy our CDs!” The crowd was less enthusiastic, but the funk went on.

Dapper was feeling the spirit and brought it with him outside into the Texas swelter where Man Man was heating up. No mentions of God were coming from the neo-glow war paint tribe on the stage but their experimental electro wail project seemed tapped into the same concept, like an ecstatic fire ritual around a blaze of computer technology. Dapper ripped off his shirt and danced in circles like a desert spirit caller when someone passed him a peace pipe that made the broken synthesized hooks and cacophonous but repetitive drum breaks melt into something reminiscent of a time when sounds, rhythms, and smoke signals were the only forms of mass communication. Man Man was weird and twisted and Zappa-esque, but the difference was this beat, this rhythm, this beat that grabbed onto Dapper like a rip tide, flipping him, twisting him, pulling him skyward, dropping him to the ground and flying over him with soothing chaos like the colors echoing from the faces of the bearded guys making the music. They were experimental in their sound and fundamental in their soul.

It was getting hot, really hot. Sweat was stinging Dapper’s eyes; back to the tent, to cool off. There was a band there from Senegal. A sparse crowd, too. Dapper was surprised at the low turnout. If a festival in the center of Texas is going to fly a band from the coast of Africa to play an afternoon slot on a side stage even though no one in Austin knows who they are, there must have been a reason.

Two men stood in front of Dapper wearing green baseball caps that read “Senegal” on the back. He tapped one of them on the shoulder.

“Are you from Senegal?”

The two men turned around and smiled. Their teeth looked like pearls on a black dress, huge and bright against deep toned skin. They both nodded looking tall with pride. Dapper resisted the urge to ask, “Do you know the guys in the band?” It’s an odd piece of human nature that assumes everyone from the same place knows each other. They turned back to look at the three brothers known as Les Freres Guisse taking the stage.

The band all had the same pearl on a black dress smiles as the guys standing in front of Dapper. One of them picked up a see through guitar, an electric fret board with the shape of a frame outlined in metal. He said hello to the crowd and Dapper said hello back. Immediately the three brothers broke into honey dipped harmony that interwove sound like air was weaving a giant bread basket to hold all the notes. The people moved their feet in time to the drummer’s left fist thumping a giant gourd while his right hand sang each skin tap with hits that flowed through the music like the taste of fresh fruit. The guitars’ gentle triplets swayed like women’s hips and the songs danced out from behind the pearls like secrets told under the sheets. Dapper felt his heart draw open its blinds as the Senegalese family sang lyrics in a language he didn’t speak but somehow seemed to understand perfectly.

“Some people say we play blues music,” one of them said. “But I tell them, this is where blues music came from.” And it was true, except this was music before it was turned blue by the chains of Colonial Slavery. It was the sound of liberation. It was the sound of Dapper’s dancing becoming the sound of Senegal’s dancing with Texas becoming the sound of possibility for a world where faith in a higher power has become synonymous with belief in an unlimited Gross Domestic Product. These brothers somehow turned the art of joy into a song. When the drummer hit his gourd so hard it split in two, the crowd gasped. He laughed and pulled another giant shell from beneath the kit and continued the way a heart might just skip a beat because of excitement.

“You’re country’s music is some of the most beautiful in the world,” Dapper told the man in front of him. Perhaps another generalized assumption about a country, but pearls are often found in the same sea. “Thank you,” said the man, shaking Dapper’s hand while the band broke into a chorus of “Nelson Mandela”. Dapper considered how strange it would be to sing such a hopeful song about an American political leader. “Mandela” bellowed through the crowd like a peace mantra in a way that “Bush,” “Cheney,” or “McCain’s” harsh syllabic finality could never ring. It occurred to Dapper, though, that Obama, at the very least, might sound good in a chorus.

Dapper’s open heart led him off the grounds, down to the campus of the University of Texas. He’d been invited to a taping of the Austin City Limits television show — the impetus for the three-day festival’s name. He met a friend outside of the studio where they were sitting against a wall waiting in line. His friend had recently had a vision of a goddess.

“She was beautiful,” his friend said. “At first, I was freaking out a little. It all felt a little too intense. I felt like I was floating out of my body. She was there, though, kind of guiding me along. She just kept whispering, it’s all just thinking, ride with it and I knew I could trust her. She was beautiful.”

“Who was she?” Dapper asked.

“She was the Mother of Creation.”

The friend stood up. He began singing:

You say I’m CRAY-ZAY!

The doors opened and the line went inside. Dapper and his friend rode a capacity elevator the three floors up to the studio. There were long tables filled with rows of free Shiner in plastic cups. The tables with the honeycombs of cups looked like giant beer pong games. His friend grabbed one cup for each hand and they sat in the second row.

There is a fake tree in the back corner of the ACL studio. A camera perches behind it on a raised platform. On television, it appears that it is shooting the stage through leaves in a park. It is really just a small piece of a tree, though, enough to create the illusion. Behind the band, there is a façade of the city skyline. Dark, non-descript buildings contrast with bright images of the school bell tower and the Capitol building. On television, this shadow contrast creates a perspective transformation of two dimensions to three.

The towering room was filled with dry ice smoke to soften the appearance of the lights. The seats surrounding Dapper and his friend filled up first because they were the best view and, also, the most likely to get seen on television. Two women sat next to Dapper. One leaned over to him.

“Best seats in the house,” she said. She was probably his mother’s age and had a Tennessee belle accent that Dapper thought sounded sugary cute at any age.

“Because they’re next to us?” he asked.

Her face warmed a little and she gave him a tap on the wrist.

“Watch out, now, my boyfriend’s the sound engineer.”

Dapper’s friend had already downed the two beers and was showing it. He leaned over Dapper and started spitting the kind of polite game reserved for friends’ mothers.

“He must be pretty trusting to let a couple of fine young ladies like your selves sit all alone over here.”

The other woman chimed in. “Well aren’t you a sweetheart.”

“I’m very mature for my age,” Dapper’s friend said. “And charming. I’m going to get another two beers for myself. Would you two like any?”

The ladies declined. Dapper’s friend tripped climbing over the couple in the row in front of them.

The house lights went down and bulbs in the fake city skyscape went on. The studio audience cheered while Cee-Lo and Danger Mouse strolled onto the stage looking like lounge show undertakers draped in black overcoats. The rest of Gnarls Barkley followed. They tore into their set, Danger Mouse playing simple chords in repeat on a church organ, Cee-Lo singing like a fallen preacher, and the band looking like Saved by the Bell nerds translating tricky album production into a live show. A boom camera craned around the stage like a curious emu checking out the action without getting too close to get eaten. At each song’s end, camera’s whirled onto the audience and Dapper always played it cool, cheering like a fifteen-year-old girl whose boyfriend Chet just scored the winning touchdown for Riverside High. He made sure not to look at the camera so that they would look at him screaming his brains out.

Ha ha ha! Bless yo’ soul.

By the time the band made it to their obligatory crowd pleaser, Cee-Lo’s voice had turned from its aged-sipping-scotch liquid croon into a rail drink rasp. He’d blown his voice pretty hard and had stripped into a soaking undershirt. The lights, so elegantly laced over the band like a television smoke screen, now made the sweat drops leeching on the man’s bald head look strange and large like make-up on a corpse. The towering ceiling and calculated sound dampeners that turned each note crisp and intelligible for at-home audiences had ulterior effects that noticeably dropped the energy dead at song’s end. Without the hums, buzzes, and feedback distortions that link one number to the next, the band couldn’t rely on the momentum they’d built through the show. The singer seemed strained to compensate and his lungs were taking a beating. Still, by the time he was screeching I remember when, I remember when Dapper was on his feet with the rest of ACL, moving in rapturous enjoyment of Gnarls Barkley’s guiltiest pleasure that chased the band like a specter of one hit wonders lurking around each recording they’ll ever make.

You say I’m CRAY-ZAY!

After the show, the Tennessee woman invited Dapper and his friend to see her boyfriend’s sound room. It was filled with tiny television monitors and a giant digital sound board that looked incomprehensible like the Tibetan language. They watched playback of the show, thanked the crew, and pretended to look lost and confused as they left trying to “accidentally” walk into the taping’s after party. The staff pretended to look helpful and oblivious as they clearly guided Dapper and his friend out of the doors.

They walked out onto the campus. They sat on the quad, staring at the giant Texas state Capitol building.

“What would you do if it all collapsed?” Dapper’s friend asked.

“If what collapsed?”

“All of it. This country. All of our lives.”

“Jesus, it’s not that bad.”

“We’re like 7 trillion dollars in debt. Shit’s collapsing. People just keep thinking someone’ll fix everything. What’s keeping it from all falling apart? This is gonna be worse than the Great Depression. I’ve thought about it a lot. I’d shoot someone if they attacked me.”

Dapper lay back in the grass and looked at the moon.

“Just because it’s not the best case scenario,” Dapper said, “it doesn’t mean it has to be the worst.”

“Yeah, but are you prepared, Dapper? What if it does?”

“Look, man, what are you scared of? Are you scared for the world, or are you scared to die?”

“There are worse things than dying.”

They were quiet. The sound of the cars on Guadalupe blended with the crickets in the campus trees. The capitol dome lit up in the sky the way it did in the studio façade. Dapper started singing.

You say I’m CRAY-ZAY!

“What the fuck would you do, Dapper?”

IV.

What the writers say, it means shit to me now.

Plants and animals we’re on a bender,

When it’s eighty degrees at the end of December.

What’s going on?

— Band of Horses

On the third day, the dust rose. Clouds of dirt blew across the field.

The town is so small, how could anybody not look you in the eyes or wave as you drive by?

Dapper was going to disintegrate today. He would see her during Band of Horses. She was wearing white. Her eyes were round and soft when they met his.

The world is such a wonderful place!

In the morning, Abigail Washburn sang songs from China and the Beatles, her and Bela Fleck trading off-kilter banjo licks as two parts of a quartet. Their twangs danced seamlessly through their international canon. In this roots waltz, Dapper sensed the repetition of the banjo’s movements as a circular wheel for the masculine and feminine interchange, Washburn’s playful plucks softening the virtuosic complexity of Fleck’s rapid fire fingers. The sun was heating Dapper’s neck.

Across the festival, David Rawlings backed Gillian Welch’s melancholia. They played on a main stage that made the two Nashville giants seem tiny and vulnerable with just their acoustic guitars. The dust blew Welch’s hair into her face and her skirt against her body. Dapper saw a woman in the crowd with a beard who was dancing with another woman. A teenage boy was kissing his girlfriend nearby. The two singers had perfected their duets like that kiss. They sang, “Oh, me, oh, my-oh, look at Miss Ohio, she’s running around with her rag top down, says I want to do right but not right now.” When Allison Krauss joined them at the end they sang, “Oh sisters, let’s go down, down to the river to pray.”

The dust continued to rise with the sun. Dapper walked by lines of toilets and noticed that people had begun wearing bandanas around their faces. He thought it was because the smell from the johns was lingering in the thick air. A young blond woman wearing large sunglasses and a skirt and a bikini top walked up to Dapper with a trash bag filled with plastic bottles. He gave her his recycling and asked, “Did I see you yesterday at Les Freres Guisse?”

She nodded.

“What an amazing show, huh?” He was hoping she might be into checking out a show with him. Or just have a conversation. The festival was getting hot and sticky and a little company would ease the swelter.

She nodded again and walked away.

Dapper was feeling a little burned. The sun was feeling like a Texas barbecue. He headed to the tent stage. There was an Australian there named Xavier Rudd. He had a beard and bare feet and he played the guitar and hand drums and didgeridoos. He and a kit drummer hypnotized their crowd into a sweating mass of grooving environmentalists singing praises to Mother Earth. Rudd’s didgeridoo solo seemed to embrace the stage like rumbling cave noises deep within the womb of the planet. The packed tent vibrated with movement and collective rhythms, dreadlocks and sweat. The show was a sad love song to the spectacle of natural beauty, made heavy by the fear that the lover was dying. Still, the two on stage electrified Dapper and the rest with tribal rhythms that served as a reminder that the way of the world might change and drop away, but the way of the universe remains. They finished the set with “Rockin’ in the Free World”. Everyone sang along. Dapper left feeling connected with everything.

The early evening brought with it a gaze of washed out blue over the park. The festival seemed more crowded than it had before. Now, though, the bandanas that covered the faces of people near the toilets were protecting faces all over the place. With darkness rising, Dapper had the eerie sensation that the dusty, dry ground and all of the masked concert goers were beginning to resemble a riot, some sort of protest to the toxins oozing through the air, through the streets, through the globe. Large groups of people covering their faces can seem unsettling. It is as if, without identity, the individual is free to act with the collective. It is a short leap from collective to revolution, but also a short leap from collective to collapse. Dapper thought of his friend, paranoid and disillusioned.

Wheelin’ through an endless fog,

We are the ever-living ghost of what once was.

Dapper tripped over a couple of legs and repeated “excuse me” as he found his way over a labyrinth of limbs already planted in central spots close to the stage. Band of Horses wouldn’t be on for an hour, but, already, prime real estate had been claimed. Most of the eager had shown up for Blues Traveler just to ensure their spot. Dapper squeezed in next to a group of high school kids and a guy with scraggly hair sitting alone. That guy’s friend appeared somewhat suddenly and sat down like a whirlwind of conversation.

“I just took a piss with three people,” he said. He wore a headband and a big beard and really short shorts.

“Couldn’t hold it?” Dapper asked.

“Hell no. We’d been waiting in line for so long we just figured, ‘fuck it,’ this ain’t nothin’ we haven’t seen before. So three of us got on the urinal and the woman sat on toilet.”

“There was a woman, too?”

“Yeah. We couldn’t just have a bunch of dudes in there.”

The Beard looked a little taken aback at the possibility of any homoeroticism involved in his story.

“It wasn’t like it was a sword fight or anything.”

He took out a bowl and packed it with green herbs. Dapper asked if he thought Band of Horses sounded a lot like My Morning Jacket. The Beard looked offended.

“Only the voice is similar. They’re a totally different band. Totally. Different.”

He offered Dapper a hit. Dapper obliged. The Beard had a very fast way of talking that altered between nervousness and excitement. His humor bordered on sarcastic while never crossing into the tentative boundaries of irony. As the THC soaked in, Dapper found the Beard’s energy both fun and a little overwhelming. Suddenly, all of the laughter around him and the growing numbers of people waiting for the band felt less inspiring and more constricting. He couldn’t concentrate on any one conversation for more than a couple of seconds. He needed space and he was sorry that he’d have to give up the company of his new friends and his spot so close to the stage. But something inside him wanted to breathe. So he lied.

“Uh, I gotta take a piss.”

If my body goes, then to hell with my soul,

We don’t even know the difference.

Dapper trekked outward past all of the faces looking surprised that someone would leave when they’d all spent so long waiting. He made his way to the edge of the crowd and walked without direction. The sky was almost dark now. He wasn’t sure why he was lingering at the outskirts; he wasn’t sure where to go. But something was pulling him. He felt like he was following something that wasn’t there.

Is there a ghost in my house?

He found himself walking inwards again. He thought he’d just walk in as far as the crowd would let him. He stopped at a small opening where there was a little space for him to move. The spot felt right. The band came on the stage.

No body’s outside, there’s no one really at all,

What the hell I saw?

As Band of Horses hooked the masses of people in front of them, Dapper looked to his right and saw her. She had brown skin and brown hair and an all white skirt. She stood at the other end of a blanket. Two of her friends were between them but she was all he noticed. Her eyes were soft and round and they met his. He smiled and they both turned to look back toward the stage.

The band was perfect. They were not an imitation of My Morning Jacket. They were their own hooks, verses, and choruses and there was not just one voice on the stage. There were impeccable harmonies. There was even lead singer Ben Bridwell’s downright soul croon that extended their range well beyond the constraints of the pop music they had adopted. The band’s warmth washed over the crowd like an evening stroll through the hills of South Carolina. After each song Bridwell thanked the crowd for being there with hospitality resembling shock that so many would want to hear them play. And after each song, she looked at Dapper, and she began smiling, too.

It was when the band slowed down that Dapper felt his chest curtsey like a debutante at a cotillion. He knew she would be looking at him as soon as he heard the A flat chord of the “Marry Song”. He knew it before he looked himself. He knew she would be waiting for him to look, too. They sang:

I’ll marry my lover in a place to admire.

She was looking at Dapper, and when he turned to see her, her eyes grew large like she had seen a ghost. He looked back at the stage, and when he turned again, she had moved. She had switched places with the friends that stood between them and was standing so close to him the skin of their forearms could brush if one of them swayed to the beat of the song.

He leaned in to speak into her ear.

“What is your name?”

I don’t have to even ask her,

I can look in her eyes,

And thank God that I am forgiven.

“Mariposa.”

Lucky ones are we all ‘til it is over,

Everyone near and far.

“My name is Dapper.”

She extended a hand and he took it, squeezing it gently and letting go.

When you smile, the sun it peeks through the clouds,

They stood swaying together while the band played A flat, E flat, D flat.

Never dying, for always be around and around and around.

Dapper felt his chest disappear first. It opened and dropped away. The air that had felt so thick became the notes of his breathing. His mind, the thoughts that carried with it the stories of people he’d met, the uncertainty of a tumultuous globe, the sense of Dapper LeChampagne uncoiled like a hurricane easing and becoming a part of the ocean. He was no longer Dapper and I looked at her again. I wondered if this would be a moment that changed the course of my life. There was no time in this place, there was no I or her or them. It was more than the economy or the election or the sadness of dying. It was a moment of love, the eternal reality of being. It was the place where music is written.

The band slowed further. They sang,

Always in time, I’m never looking over my shoulder,

I sing to you, I sing it to you.

Dapper took a deep breath. He leaned in close.

“Mariposa,” he asked, “would you like to dance?”

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)