One of the great book titles of the last 15 years is Wicked: The Life and Times of The Wicked Witch of the West. I read it before it became a franchise, complete with touring Broadway show and coffee table book, when it was still getting nasty reviews for its political correctness and moral relativism, as though this work of fantasy was ultimately about such things.

Wicked passes one of the great tests of fiction, which is to create a convincing and consistent world, which Maguire has done, though he borrowed that world from the great Frank L. Baum. To be sure, he twisted Baum’s pleasantly conflicted child’s fairytale of fake wizards and evil witches into a darker adult’s world of vicious social climbing, power politics, animal chauvinism, and, yes, witch sex.

The sequel, Son of a Witch (another great title), was a letdown. The story of Liir, the rumored son of Elphaba, the eponymous witch, while rich in invention, meanders and is soured by Liir being not only unlikable, but a gloomy bore. The ending, in which Liir’s newborn daughter “cleans up green”, like her grandmother (Liir is not green-skinned), is a thrilling moment and makes it clear that Maguire plans to be writing about Oz for a long to come.

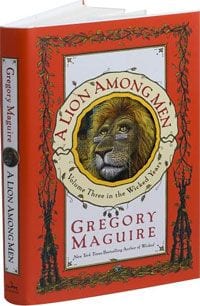

The third volume in what is now called the “Wicked Years” series, A Lion Among Men recaptures some of the magic of the first book. Set nine years later, it chronicles the life of Brrr, the Cowardly Lion. (I’ve read most of the Oz books to my daughter and note that though Baum wrote both The Scarecrow of Oz and The Tin Woodman of Oz, none of his books featured the Cowardly Lion. Perhaps Maguire is evening the scales.)

Less a coward than a clueless and unlucky outsider, Brrr was orphaned as a cub by tools of the evil Wizard of Oz, who has authored the “Animal Adverse Laws”, attempting to subjugate “Animals” (animals who can talk) and force them to return to their proper sphere among the “animals” (those who can’t). (One could be tempted to read 20th century history into these books, but Maguire is more interested in character—whether one has it or not—than issues of historical significance.)

We follow Brrr on his journey toward self-discovery, from his youth as a lesser light at a university town, to his debacle with Dorothy, his years wandering among feline communities and as a financial broker for other displaced Animals. In each instance, Brrr is victimized, unfairly accused of some misdeed, and either driven off, or, eventually, thrown in jail. Freed, he is forced into the spy services of the current Holy Emperor of Oz, Shell Thropp, Elphaba’s currupt brother, and charged with discovering the whereabouts of the Grimmerie, Elphaba’s powerful book of magic. (Along the way, we are also treated to a scene of, yes, big cat sex.)

The envelope of the novel is Brrr’s interrogation of Yackle, an ageless maunt (or nun) at a mauntery south of the Emerald City. Yackle appears to have been born an old woman and is now blind, but considered to be a seer. She is incapable of dying. Through her, Brrr learns not only the facts of his own origin, but much more, including the story of Liir and his daughter, and the secret to Yackle’s seeming immortality. In the end, he manages to slough off his own self-absoption to commit himself to the welfare of someone else in a search for Liir and his daughter.

The novel leaves us with Yackle’s tantalizing declaration, “She’s coming back—“. Is “she” the banished and presumed dead Ozma, once benign ruler of Oz, or the fairy goddess Lurline, or even Dorothy of Kansas? Or, as I suspect, will “she” be a new “Wicked Witch of the West” in the form of Elphaba’s verdant granddaughter? We’ll have to wait for Volume 4, or longer, to find out.

For all their magic and invention, both A Lion Among Men and its predecessor are flawed by a more-than-occasional coarseness, violations of tone, and tone deafness. When Brrr, an otherwise gentle spirit, says, “Fuck you!”, the book almost comes apart in your hands.

The men and women, and the Animals, of Oz are as sarcastic, foul-mouthed and nasty as anyone you might meet in a bar. There should be a word, maybe “tonal non sequitur”, for dialogue that might follow logically from what came before, but violates the tone of both the moment and the characters involved. Unfortunately, this book is infected with it.

Just one example: interrogating Yackle, Brrr betrays interest in the possible affair between two of Liir’s lovers. Yackle says, “Is this germane to your interrogation, or do I detect a particular interest in sexual jealousy? An uptick in your circulation? Some shallow breathing?” Brrr replys with the F-bomb and Yackle says, “If I’d only been so lucky.” Nowhere else does Yackle betray the slightest libidinous impulse, nor could she, being an ageless desiccated half-corpse desiring only her own death. Even worse, Maguire intends her comeback to be funny. Oh, my.

“Wicked Years” is a grand project. In the original Oz books, Baum’s imagination often flagged, forcing him to inject new characters from book to book, usually more in service to novelty than plot. Maguire has taken the Oz template, character and place, twisted it toward the dark side of adulthood, added a number of his own inventions, plausible and interesting extensions of the original, and made it his own. Now, if only he could capture the voice of Oz.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)