Philadelphia officials and university leaders say it’s important that more of Philadelphia’s talented young people stay here as they begin their working lives. The city, we’re told, needs their youth, their energy, their idealism.

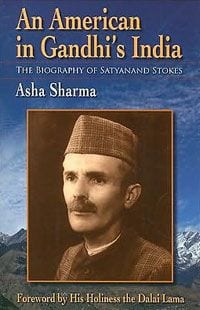

True enough. But sometimes the greatest gift a city can offer the world is a young person, formed in its finest traditions and beliefs, who ventures off and brings the glow of unquestioned integrity, the fire of altruism, to those who need it even more.Satyanand Stokes (1882-1946), nee Samuel Evans Stokes Jr., was such a native son. His astonishing life story, first published in India in 1999, now happily arrives home in a handsome US edition.

You’ve probably never heard of Stokes, but Mohandas K. Gandhi did. And it’s not every day that the Dalai Lama writes a foreword to a book. Satyanand Stokes attracts those sorts of admirers.

At age 21, Samuel Evans Stokes Jr., the firstborn son of a Philadelphia Quaker family that stretched back to the era of William Penn, set off for India’s Simla Hills to work in a home for lepers.

Stokes initially tried to emulate St. Francis by forming a religious brotherhood. Before long, he went Indian. He took on local dress, rejected the privileges of a white Westerner, gave away his belongings, and adopted the name Satyanand.

In 1912, he married a local woman, a marriage that produced seven children. Living near Shimla, the summer retreat of the British Raj, Stokes introduced American Red Delicious apples to the Himalayas in 1916, forever changing the local economies. In 1924, he opened a school to educate the children of local farmers, putting special emphasis on the education of girls. The new activist for concerted social action also led a successful fight against begar, a system under which local rajas and the British exploited poor, uneducated hill people by forcing them into free labor.

Later, Stokes became a leader in Gandhi’s independence movement, the only American member of the All India Congress Committee. He also ended up the only American ever imprisoned by the British (six months) for involvement in that cause. In 1932, he converted to Hinduism, in part because he detested the Christian notion of eternal punishment.

Asha Sharma, the author of this lovingly detailed and enormously moving biography, is a granddaughter of Stokes. She graduated from Columbia University’s school of journalism and served as a research associate at the University of California, Berkeley. Her excellent combination of smooth storytelling and primary-source digging (drawing on such family material as Stokes’ 25 years of letters to his mother back here) reflects those affiliations. Sharma makes Stokes’ story alluring in both its early Philadelphia moments and its long unfolding in India.

His father, Samuel Evans Stokes Sr., was the founder of the Stokes & Parrish Machine Co., one of America’s first major elevator firms, which later merged with Otis. The family lived in Germantown, and Sam Jr. attended Philadelphia’s Quaker Penn Charter School, and later Cornell University.

Stories of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table instilled in young Stokes, his granddaughter explains, powerful impulses toward justice and honor. As a boy, he helped older people cross the road. He once gave his whole money box to a woman who came begging at the family’s door.

Later, in his adolescence, Stokes experienced a spiritual awakening that further fueled his bent toward service. Already teaching Sunday school at Germantown’s Calvary Church, he and a friend founded a boys club that grew into the Southwark Neighborhood House. So when Marcus Carlton, a doctor devoted for 20 years to treating lepers in India, gave a talk in Philadelphia about his clinic’s need for workers, Stokes proved an ideal listener.

Stokes’ father offered him $500 a year for five years, sure that Sam Jr. would eventually come back and take over the family company. He never did return, except for visits.

In India, Stokes and Gandhi formed a mutual-admiration society. Writing of Gandhi in 1921, Stokes described himself as “more and more convinced that the movement which (Gandhi) has initiated calls us to the deepest and noblest in our nature.””It is that old call to victory by the path of utter self-renunciation, to purification by the path of self-sacrifice.” Elsewhere, Stokes described his link to Gandhi as “the part of my life of which I am most proud.”

But if Stokes’ own writing sounds decidedly Gandhian, Sharma’s section on his boyhood shows that his heart was in the right place long before. “If we fight with the ignoble weapons of pride and hate and prejudice,” Stokes wrote in one article, “we are undone, even if we win a sort of immoral victory. If we fight in the spirit of true nobility, God and eternal justice fight for us, and the victory is certain.”

Gandhi, for his part, praised Stokes’ campaign against forced labor, telling him, “In your efforts, I am with you with all my heart and soul.” When the British arrested Stokes on 3 December 1921 for sedition, Gandhi responded with a front-page article in his weekly journal, Young India. That Stokes, Gandhi commented, “should feel with and like an Indian, share his sorrows and throw himself into the struggle, has proved too much for the government.”

Toward the end of his life, Stokes wrote that he believed he had “kept the faith” with his Quaker ancestors. “The struggle for right and fair play in the relations of men,” he observed, “is a fight worth fighting.” Though Stokes conceded that many of his dreams of service had met with only “imperfect realization,” he added, “yet the dreams were something.”

In the Nehru Memorial Library in New Delhi, Satyanand Stokes’ portrait hangs among those of the other leaders of India’s independence movement. It’s a long way from Philadelphia. Roughly the distance from one heart to another.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)