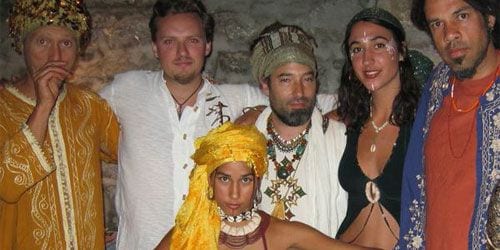

Hamsa Lila has certainly matured over the years. Since borrowing elements of Moroccan ritual music for their 2003 debut, Gathering One, the San Francisco-based sextet has created a new modality for trance, once again proving that while forms rearrange, essence remains the same. For this four-man, two-woman outfit, the forms include traditional Gnawa instrumentation — the bass lute, sinter, the hypnotic metal clappers, krakebs, and stringed instruments such as the saz and oud — with the foundational guitars, bass and drums. The essence is a mesmerizing gaze into the future of world music.

Lila’s breakthrough was a case of stating the obvious. Oddly enough, the obvious is not always realized. By taking the low-end sinter and boosting intensity during production, allowing this instrument and not the percussion to lead each song, they essentially updated a Middle Eastern ceremonial music form with dance club aesthetics. While the sinter was always the driving force of Gnawa trance music, in the studio it has been, time and again, consumed by the rapturous chatter of metal clappers or various percussion instruments, not to mention gorgeous Arabic vocals. Enter Yossi Fine.

Few musicians have amassed a resume as impressive as Fine. Not only does he perform with world-class artists, but he often helps to define their sound. Since the ‘80s he has been pivotal in the evolution of bass, creating some of hip-hop’s most memorable bass lines (Hip-Hop Hoorah, ho, hay…) and touring with jazz legends such as Ruben Blades, Gil Evans, Stanley Jordan and John Scofield. Since creating Ex-Centric Sound System in 2000, he has released progressive albums surveying the state of modern African and Jamaican music. Since then he has recorded with and produced the likes of electro-tabla virtuoso Karsh Kale, Algerian DJ Cheb i Sabbah, Afrobeat innovators Antibalas and Moroccan trance master Hassan Hakmoun — not to mention, of course, Lila.

He took the band’s youthful and raw energy and gave it form and shape through the process of bass. The deep prowess of “Eh Musthapha” and “Turka Lila” was the result of his studio alchemy, and as shards of reggae and African music seeped in, you realized this was more than a Gnawa-inspired jamband. With the release of the rich and unforgettable Live in Santa Cruz (In the Pocket), Lila takes this lush tapestry of sound into the arena in which they excel: the stage.

Lila is the ceremony in which the Gnawa commune with mlouk, supernatural entities. Borrowing from the Sanskrit lila — one of the most important and fundamental components of yoga philosophy — the all-night ritual peaks near dawn when dancers and musicians become so engaged in the ceremony that no separation between themselves and the dance, or the music, exists. As in yoga, everything is part of the “union”. This concept is challenging to the Newtonian mechanical West, in which opposites play distinct and conflicting roles. In a physical class, for example, when all parts become the whole, when movement and breath are one and the same, yoga is achieved. For the Gnawa, this merger is of dance and music.

The American jamband scene, heralded by the likes of the Grateful Dead and evolved by Sound Tribe Sector Nine and Lila, both of which are as in touch with the electronic realm as well as live performance, is a product of this human continuum of trance. Many years ago, bassist, producer and record label owner Bill Laswell mentioned to me that very often a song does not even get going until 20 minutes into it, another challenging idea to a culture bred on four-minute pop standards (which he dubbed a “business idea”, not music). The Gnawa knows this, just as the virtuoso of Indian classical music. The alap must build for some time before the actual movement can begin. In yoga, you start with breathwork before asana. In a Hamsa Lila show, you gently coax the bass from the deep before it comes to dominate the psyche.

So it goes with the opening invocation, “Om Tara”, again showing the band’s worldly fixation with an oud-led mantra. (The guest oud player’s name is Ganapati, a headnod to the revered elephant-headed deity.) While the sintir and percussion is distinctly masculine, Lila plays the Shiva/Shakti edge with two exceptional female vocalists, Deja Solis and Nikila Badua. They trade time through the 13 songs with their male counterparts, mostly m.j. greenmountain, who both disdains capital letters and does an excellent job on various percussion instruments. But the sonic epoxy of this band is Inkx Herman, a drummer with a notable career backing up African musicians (Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Abdullah Ibrahim), not to mention sessions with Paul Simon and Sting.

The globetrotting continues as the digeridoo, tanbur, and various flutes and drums emerge through the band’s extended set. Most interestingly is their “Western” song, “Eyes”, which features a traditional synthesizer/ drum/ bass/ guitar line-up, lyrics in English, and the tasteful inclusion of Evan Fraser’s jaw harp. Even hip-hop gets a nod from these expansive cats, on the midtempo “Auroroa”, another track held down by Herman’s cadence and Vir McCoy’s meditative bass line, a feat he repeats over and again, be it on the four-string or its Moroccan counterpart.

Yossie Fine

While Lila is inviting extra players into the circle, Fine does the exact opposite on his latest, Live in Jerusalem (EXS). I remember DJing with Yossi one year ago, in fact, and asking him what he was up to. His face suddenly beamed: “I’m doing a one-man bass tour.” Having known the man for a number of years, fully aware of both his live and studio capabilities, I nodded, though uncertain of exactly what that could mean. His shows, for the most part, are not sit-down small theater gatherings, at least not when he returns to Israel, where half his bloodline derives. His shows are held in large theaters that hold hundreds, if not thousands, of fans. How one man could hold down a crowd of that magnitude for two hours was beyond me.

It was until I listened to this album, distilled to 45-minutes and four songs, I understood. That’s not to say I know how he does it, or exactly what “it” even is. Few people are brave, or crazy, enough to stand on stage with a few simple drum loops, an effects board and a bass, and go for it. Yet that’s exactly what he does, amazingly well, to boot. Like Laswell, Fine is more interested in sound than songs. So the landscapes he paints are orchestral, lush and textured. He relies as much on what’s not played as what is; hence, his understanding of concepts like space and gravity are naturally embedded into his art. That he can make his electric bass sound like a guitar, keyboard or an upright is, in some ways, a matter of technology. The way he makes them sound that way is completely his own. One minute strains of Jaco Pastorius emerges; a few beats later, a throbbing white wall that would make Les Claypool shake his head, before dropping into a dub groove reminiscent of Robbie Shakespeare.

To be fair, Fine does not do it completely alone. Part of the tour includes guests from whatever city he happens to be in. He certainly had a lot to choose from in his motherland, and on this disc appears an excellent horn section on the dubby “West Nile Funk” from his album of the same name (here renamed “West Nile Style”), thanks to Yair Slutzkit and Sefi Ziezling. More brass appears on the exceedingly funky “Calabass Party” featuring Yaron Mohar. Fine winds down by kicking things up on “N.L.B. In Jerusalem”, a mind-spinning track that takes slapping to a new level — another form of trance induced.

And that is a maxim many folk and modern forms of music have relied upon; the repetitive tones of low frequency to numb the mind and loosen the hips. Shamanic drummers knew the power in this, as did Nyabhingi percussionists that influenced early reggae. The tradition continues with new toys and technologies, but never forgetting that the heart and soul of trance lies in the passionate intensity performed by its players. These two albums are remarkable examples of just this.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)