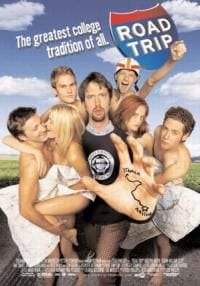

The success of last year’s American Pie has paved the way for a resurgence in young-white-male-targeted sex-comedies. Not surprisingly, Todd Phillips’ new contribution to the genre, Road Trip, covers little new ground, wallowing in a predictable story of male sexual anxiety, enhanced by racism, homophobia, and scatological humor. On the other hand, it does feature MTV’s Tom Green.

The plotline of Road Trip revolves around four students at Ithaca College who embark on a (surprise!) road trip to retrieve a videotape containing evidence of an illicit affair. Here’s the background: Josh’s (Breckin Meyer) girlfriend, Tiffany (Rachel Blanchard) wasn’t returning his calls; in desperation, he slept with gorgeous Beth (Amy Smart). Unfortunately, this videotaped escapade ends up being mailed off to Tiffany, who has, in fact, been away due to her grandfather’s death. Josh enlists a group of fellow students with all the diversity of a boy-band to retrieve the video in Austin, Texas before Tiffany sees it. There’s E.L. (Seann W. Scott), a sex-obsessed loudmouth and party boy; Rubin (Paulo Constanzo), an overly intelligent stoner; and, of course, Kyle (DJ Qualls), an antisocial misfit and virgin who provides his father’s car for the trip. Hilarity ensues.

Things start off rough for our male foursome when Kyle’s dad’s car explodes. No problem. E.L. quickly steals a bus from a school for the blind. When they run out of money, the group ends up spending the night at a black fraternity house. Kyle interrupts a stepping routine during a party at the house, then loses his virginity to a (female) party-goer. There follows a wacky trip to a sperm bank (the boys, after all, need to get money somehow — why else wouldn’t Josh have just flown to Austin?). After Josh and E.L. make their contributions, the gang proceeds to Barry’s grandparents’ house, where Rubin smokes pot with grandpa. The group eventually reaches their destination, only to encounter a mailroom clerk who won’t turn over the package, and Kyle’s parents, who believe their son has been kidnapped. The movie ends on an unsurprising note in a witless final confrontation.

Most of the humor in Road Trip depends upon the audience identifying with the characters’ sexual anxiety. The story is narrated by Barry, who did not go on the road trip but is recounting the story for a group of unwitting prospective Ithaca students and parents. Since he is telling the story, Barry’s fantasies become the reality of the film. Early in the movie, for example, there’s a women’s locker room scene. All the women are naked, prompting a prospective student to object to Barry’s blatantly fantastical narration. “Hey, this is my story,” Barry protests. The fantasy continues with the women standing topless before a mirror, trashing men. “All men are perverted pigs,” says one. What we’re witnessing is a male-anxiety fantasy, wherein women are sexualized precisely because of their perceived power over men, turned into controllable objects. The audiences for both Barry’s story and the film are encouraged to objectify these women by associating (seeming) feminine agency with the male gaze.

This portrayal of women as emasculating menaces who can be restrained only through male sexual dominance recurs throughout the film. Josh, for example, repeatedly visualizes his girlfriend sleeping with another man. This vision of her offense is translated into an occasion for patriarchal power when Josh sleeps with Beth. Josh recognizes that Tiffany has enough agency to sleep with another man, and he must massage his masculine pride by translating this anxiety into a demonstration of his manhood. Having sex with Beth becomes a signifier of Josh’s control over Tiffany. Correlatively, the videotape signifies another threat to Josh’s presumed power. If Tiffany sees the videotape, Josh becomes the object of Tiffany’s gaze, and his symbolic act of dominion (sleeping with Beth) turns into a signifier of his own impotence, his inability to maintain control over Tiffany.

It is only fitting that it takes a gang of four men to battle the feminine threat Tiffany represents. The road trip — or rather, the car — is, in this film, a homosocial space, where women cannot enter. This provokes a good deal of homophobia, as when the car reaches an impasse in a wooded area and E.L., horrified, imagines the group’s “first ass-raping.” E.L. articulates for the group, as for the audience, the profound anxiety experienced by such all-male groupings. If there are no women around to construct the boys’ masculinity, they must seek another group to “other.” Homosexuals provide an easy target, specifically those who rape, as they represent the possibility of threatened masculinity even in a homosocial world. As it turns out, E.L.’s first “ass-raping” occurs in the sperm bank, when he attempts to seduce a female nurse. The nurse responds to his provocation by performing an invasive procedure to obtain his sperm. This could represent a shifting of the film’s paradigm, but it turns out that E.L. becomes quite attached to the procedure. The fact that he obtains pleasure from it ensures that he remains in control of his hegemonic sexuality.

The film also relies upon grotesque constructions of race in order to win the audience’s support for the group, who would otherwise be too loathsome to win audience sympathy. The whiteness of the Ithaca group becomes visible when they stop at the black fraternity house. The group has no idea the fraternity will be African American: they are relying on Rubin’s wits to gain admittance to the unknown house. When the door is opened by an African American male, the Ithaca gang respond with expressions of surprise and terror. The frat members, on the other hand, welcome the group inside to dinner. E.L. eats sandwiched between two large African American men. The audience is expected to recognize the danger in these two black bodies. The African American presence in the movie is here reduced to sheer physicality. The black “space” (the frat house) does not exist to question the foursome’s unquestioned agency as white men, but only to threaten the white boys on a purely physical level. The audience is expected to accept the fear of blackness the scene constructs, rather than interrogating the whiteness the movie otherwise assumes.

This construction of black threat/white fear is literalized when several black men hold up a Klan hood to Kyle, which they claim they have found in his duffel bag. Kyle passes out from fear, and when he awakens, he is surrounded by laughter. The whole thing, you see, has been a joke on Kyle, taking a potshot at his racist fear of black men. But, ironically, the film has constructed the paranoia that the joke purports to deconstruct. The audience is expected to understand that the white men’s fear is ungrounded, yet this scene simultaneously relies upon the audience’s capacity for recognizing the threat which attaches itself to African American men in order to “get the joke.” The “joke” that the black fraternity members play, aside from being tasteless and absurd, winds up representing precisely what the scene purports to ridicule: white men should feel threatened by black men.

Kyle receives further attention in the frat house, when he gets drunk and jumps on stage during a fraternity stepping routine. His spastic dancing pushes the steppers to the stage’s peripheries. The black space is thus turned over to a white man, ensuring that our Ithaca boys can reclaim their spatial hegemony. Kyle dances a polka, much to the amusement of the African American crowd, especially Rhonda, a large black woman who falls for him. The two end up in bed together, where Rhonda climbs on top of Kyle. “Relax, baby,” she says. “Let Rhonda handle this.” For the sake of sexual comedy, then, the film at last allows her a bit of agency. Unfortunately, Rhonda exists only to allow Kyle to transgress the law of his father. Kyle has been living in a world of excessive order, and Rhonda signifies for him the possibility of escaping by committing a taboo act of interracial sex. It becomes quite clear, later in the movie, that Rhonda’s blackness is central to Kyle’s transgression: he horrifies his father by bringing her home to dinner. Rhonda’s power and desire, manifested by her being “on top” during their lovemaking, were merely show, and are quickly subsumed into Kyle’s resulting freedom from his father’s tyranny.

One of the significant differences between Road Trip and its predecessors, such as American Pie, is the former’s complete lack of artifice with respect to the characters’ sexual dominance. Where American Pie cast its characters as ostensibly insecure in their masculinity, Road Trip constructs its Ithaca group as aggressively masculine. Its representations of the “Other” are correspondingly brash. I suspect one reason Road Trip has been so successful is because of Tom Green’s presence in the cast. Green’s MTV program is quite popular among Road Trip‘s demographic, due in large part to his no-holds-barred, sophomoric humor. The difference between The Tom Green Show and Road Trip is that Green’s pranks are often humorous. Road Trip is nothing but sophomoric.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)