First they tell you to drink, then they tell you not to drink. They tell you to be a rebel, then they tell you to kiss ass. What else do you have as an outlet? Your art doesn’t do the trick. Even your emotions are a commodity.

— Chuck Connelly

It’s easy to feel frustrated with Chuck Connelly. An expressionist painter briefly famous during the 1980s, he is today resentful that his brilliance is no longer rightly recognized. But he’s not just a raging blowhard or even a damaged ego. As angry and self-performative as Connelly may be, he is also set against a broad context, namely, the New York art scene and its inconsistent pop cultural framework.

Connelly’s story is recounted in The Art of Failure: Chuck Connelly Not for Sale, which premieres 7 July on HBO: it is at once fragmented, exasperating, and weirdly predictable. Repeatedly addressing the camera, whether wielded by his wife Laurence Groux or by director Jeff Stimmel, he offers a range of what might be termed interpersonal approaches, from belligerent to baleful to self-destructive. As the film begins, he waits outside galleries as Laurence heads inside, again and again, asking whether the people she meets might want to look at Connelly’s work. No, no, and again no, come the answers. “I thought he was dead,” says one owner. “They look pretty old-fashioned,” says another of the paintings Laurence shows. At last she enters an elevator, the space tight, the walls looming in wide-angle, and she collapses in exhaustion.

This terse preface is followed by an extended introduction to Laurence’s husband that demonstrates why she’s so fatigued. A bit of text clarifies that he was once a “rising star,” along with Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat,” who sold more than $1 million worth of art 20 some years ago. Now, art dealer Mary Lou Swift says, though Connelly is self-confident, talented, and once recognized as such, his “career has really not developed to the level of his talent.” The film doesn’t offer a neat explanation, but it does suggest possible reasons. For one thing, observes ArtNet editor Walter Robinson, “I think for most people though who Chuck is as a painter is overwhelmed by his artistic myth.” That is, he is at once believed to be brilliant but also impossible. Eduard Doga, an art dealer, pronounces, “Nobody that did more damage to Chuck than Chuck.”

The details, as much as they’re reported, also sound clichéd. Swift suggests his “drinking signifies that he’s just so miserable inside,” and moreover, that he modeled his persona on Warhol (Connelly grew up in Pittsburgh, she notes by way of explanation). “He idolizes the Jackson Pollack-Willem de Kooning way of creating art and being an alcoholic,” she says, as the film illustrates via several scenes of Connelly raging and sputtering. When, early in the proceedings, you learn the Nick Nolte character in Scorsese’s third of New York Stories was based on Connelly (who provided paintings and brushstrokes), this makes a kind of sense. It’s also not surprising that he went public with his criticism of the film on its release in 1989, though it may be surprising that anyone cared. At this point the documentary conveys that Connelly hasn’t had a major show since 1990 and now sells paintings only occasionally. Tracking an online auction, Laurence and Chuck are nervous as the price rises, slowly. When bidding closes at $550, he fumes. “Now, you people see,” he tells the camera. “You stupid motherfuckers.” When she suggests his energy is “negative,” he heads downstairs to lie on the couch, smoke cigarettes, and tearfully lament his sorry state.

It’s something of a puzzle as to why Laurence stays on as long as she does. The film trots through their past as if it is Connelly’s, with photos showing them youthful and self-conscious on sidewalks and in galleries during the ’80s, as well as snippets of home movies where she smiles as her husband extols her beauty (“You look like a painting”). When she appears to be trying to document their more recent, less happy existence, he variously abuses or forgets her, knocks over the camera or rails against the big bad sales and promotions system that has abandoned artistic standards: “All these fucking artists, they don’t have anything but PR agents, assistants, you name it, psychiatrists, drug dealers. They don’t have time to do their own work.”

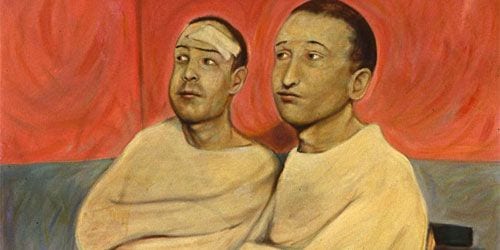

Connelly, by contrast, has all kinds of time, and so the movie shows him painting, lots. The apartment — he now lives in Philadelphia — is crowded with canvases leaning against one another and wedged into corners: two decades’ worth of portraits, still lifes, landscapes, and fantastic scenes of flying, dismembered, or naked figures. Fellow artist Mark Kostabl calls him “neo-expressionist, perhaps the quintessential one… Because the ultimate expressionist is Van Gogh and Chuck is Van Gogh reincarnated.” It’s true that much of his work uses similar warped perspectives, thick slabs of color, and intensely configured faces alternately agonized and enraptured. Robinson says of his style, “It’s not about being precise.” Instead, it’s about color and paint as texture.

He knows what’s sexy about it and what’s juicy about it. Paint is like all those things: it’s like salve and it’s like lotion and it’s like mud and it’s like shit. It’s everything that’s tactile and you touch… the paint is gonna solve everything.

Until, of course, it doesn’t. All that smearing and slapping, and grunting doesn’t solve Connelly’s umbrage or help him to feel empathy for someone else, say, Laurence. When she leaves him at last, he describes it as part of the world turned against him: “Gallery, patron, wife,” he mutters. “All gone down the fucking drain. That means income zero.” (That patron, Matt Garfield, had sent Connelly regular checks for years, taking paintings when he found spaces to hang them in his several homes; but when Connelly begins to abuse him verbally as well, Garfield signs off, their disagreement incorporated as competing Real World-ish “confessionals.”)

Connelly’s solution to his loss of income and companionship is to hire an actor to play a younger, newer, more polite version of himself named “Fred Scaboda.” Connelly, the film notes, went through a “Fred Scaboda Period” earlier in his career, signing paintings with a big black dot and imagining a sort of alternate personality. When the hired “Fred” approaches dealers with a sample book, several are intrigued and ask to see him in his space, among paintings. True to form, Chuck sabotages this meeting, by leaving “Fred” with paintings very unlike the ones he showed (“lesbian” paintings, with naked women gamboling in woods or interiors). “I felt like my hands were tied,” sighs “Fred,” “That Chuck had just really, really fucked me.”

The film doesn’t belabor the point that “Fred” is in some sense a version of Chuck, but the self-subversion in this relationship — and especially in this moment — is plain enough. The Art of Failure not only observes such behavior, but also grants Connelly opportunities to act out. In this it’s like most portrait documentaries. However disturbing Connelly’s behavior, his and the film’s reciprocal exploitations of each other, their mutual artistic productions, are at least as compelling and provocative as his paintings.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)