From PopMatters’ coverage of the Toronto International Film Festival 2007.

Warning: spoilers ahead.

From the opening scene (created personally by director, Julian Schnabel, a renowned artist) of antique x-rays to the scene immediately following (jaw-droppingly photographed by Academy Award winner Janusz Kaminski) immediately following, where “Jean-Do” (an astonishing Mathieu Amalric) awakens from a three week long coma (curiously, the second of the festival) –- only to think that nothing is wrong, the director and the technicians are able to transport the audience into another world. This is the kind of thing that I personally love about film; the ability to really connect and experience someone else’s life, visually and emotionally. Schnabel and crew miraculously do this in the first two minutes of the movie. Diving Bell feels like another world and visually, it looks like no other film.

It takes a solid 15 minutes or so to become fully oriented to the film’s pioneering visual style, likely a deliberate move on the filmmaker’s part to get us to empathize with the man’s predicament. Characters move up to the camera, getting close to Jean-Do’s face to talk to him, but essentially, they are talking directly to us.

In Jean-Do’s mind, he is still OK. We experience his thoughts through Amalric’s narration as if nothing major has happened, but then are dealt a devastating blow as the doctor’s inform him of his condition. They assure him everything will be fine. It is a strikingly filmed opening montage, especially when Jean-Do comes to the realization that he can no longer speak or move, and that no one can hear the inner monologue happening exclusively in his head.

The hard truth is that Jean-Do is paralyzed from head to toe and will never speak again. “It’s just one of those things,” says a callous doctor, at a loss for words while explaining his condition. This randomness echoes as images from the man’s childhood, and his mind’s eye come crashing all around him with a fragmented urgency; a point of view which he referred to as “the butterfly”.

Henriette (an incandescent Marie-Josee Croze) is Jean-Do’s speech therapist, who calls him “the most important job she’s ever had”. She gets him to learn the blinking code (first a simple “one blink” for “yes”, two for “no”), and makes him answer inane questions (which the narration hilariously skewers, unbeknownst to her). He flashes back to his life as a fashion director for the magazine.

After such a sweet recollection, we are confronted with more ugly truth: Jean-Do’s right eye must be sewn shut to prevent the cornea from being destroyed. Since the point of view the audience experiences is lived directly from the man’s eye line, we too get a birds-eye view of an eye being closed forever, and it is shocking. Everything is mercilessly taken away from this once-successful man.

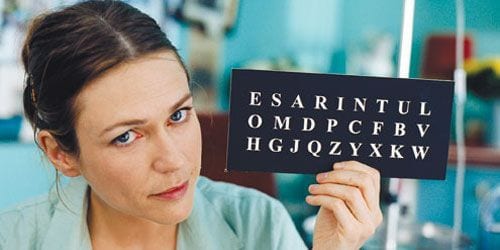

The dedicated Henriette begins to teach him a more advanced version of the blinking code, this time the alphabet, through a board that is set up by frequency of letter usage. In a scene where she has a breakthrough with him, thrilled at the prospect of communication with the man; she ends up not getting the kind of responses she had hoped for — Jean-Do wants to die. In a lush scene on the beach (where the hospital is located in France), she convinces him that there is still purpose in life. It’s a very tricky speech; one that could have been contrived or sappy, but Croze underplays it with supreme elegance.

The unpredictability of the accident is mirrored in the unpredictability of the imagery in Jean-Do’s mind. A glacier dissolving and crumbling into the sea, a sumptuous green valley, a flower being pollinated; these seemingly unrelated shots all figure in prominently with the poetry of the man recalling his life (and the poetry of the Oscar winning scripter for The Pianist Ronald Harwood). He tells us that some of it is real and some of it is made up, but it keeps him alive. “I can imagine anyone, anywhere”, he says as more odd pictures are displayed onscreen.

He imagines a life that is not really his own, but that of Marlon Brando; until we finally get a chance to see what his life was like when he wasn’t strapped to a chair. At this point, the point of view changes once again, and Jean-Do becomes a character in his own story. He begins to dictate his memoirs to a nurse, feeding her poetic ruminations on the life he once led, and freeing himself of past shackles in the process. He recalls, in touching fashion, a day with his 92-year-old father (a brilliant Max Von Sydow), where the men talk about living to be old; then there is a telephone scene between the two men that had many audience members reaching for the Kleenex.

Amalric is able to convey more pathos with one eye (and his voice in the narration) than most actors can do with their entire body. With this performance (and solid work in the under-seen Kings and Queen), the actor proves to be one of the boldest, most talented working. With his privacy stripped, completely dependent on others for everything, and everything taken away from him, Amalric’s Jean-Do cleverly figures out a way to become expressive once again, and it is genuinely beautiful and heart breaking to witness not only the death of a man, but also his artistic rebirth that gives him grace in the end.

The director is particularly adept at putting all of these pieces of film together like an assertive artist with a distinct vision. The film plays out like a painting in many scenes — a smattering of soft blue here, a touch of fleshy pink there; and it all comes together bathed in a golden halo of sunlight. This is more special than the hundreds of other run-of-the-mill bio films that have been produced ad nauseum over the last few years. Schnabel continues to innovate, and this is hands down his best film.

Schnabel’s previous two efforts (Basquiat and Before Night Falls), both highlighted the true-life stories of creative types (one a painter, the other a poet) who have to overcome insurmountable odds to release their demons and turn their visions into art (it is rumored that Schnabel’s next adaptation will continue along these artistic lines with an adaptation of The Lonely Doll with Naomi Watts and Jessica Lange). These films are all tied together with the thread of art and what it means to be or to become a true artist, and each has Schnabel’s distinct stamp of personal artistry on it.

The final deluge of choppy imagery, as Jean-Do lay dying, and is visited for the final time by his loved ones, is some of the most haunting, beautiful photography I have seen this year and I will carry them with me for a long, long time. I don’t think a director (other than maybe Ingmar Bergman) has ever so eloquently captured the personal experience of dying as Schnabel has here. “I wanted this film to be a tool”, said Schnabel. “Like his book, a self-help device that can help you handle your own death. That’s what I was hoping for and that’s why I did it.”

He takes us right up to the end, through the fear and through the acceptance. Even though Jean-Do was totally immobile and survived much longer than anyone expected, it is still tragic to learn that he died only 10 days after his book was published.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)