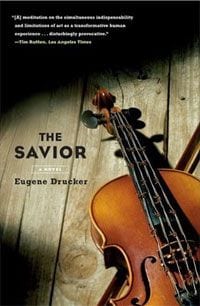

Drucker, a violinist with the Emerson String Quartet, set his debut novel in Nazi Germany. The war will soon be lost, but this doesn’t stop the Wehrmacht from sending violinist Gottfried Keller to perform for the wounded in various hospitals.

The task is a miserable one, his audiences indifferent at best, hostile at worst. Nonetheless, Keller, who missed conscription due to a weak heart, dutifully plays wherever he is dispatched. He asks no questions.

Like much of the remaining Gentile citizenry, Keller lives in fear. His worries that his diary, locked in a desk drawer, might be discovered. His sullen downstairs neighbor might report him to the SS for practicing degenerate music. Worst of all, past relationships might brand him a Jew-lover.

One chilly morning an SS jeep pulls up. Keller is driven 15 kilometers outside the city, to the “labor camp” everyone tries to ignore. The camp, never named, is comprised of shoddy wooden barracks, a train track, and an odd, windowless building topped by a smokestack emitting a vile smell.

Keller is taken to the Kommandant, who explains the building is a rubber plant—hence the inescapable smell and ash. But the plant’s operations will cease during Keller’s visit, so he may better carry out the Kommandant’s wishes.

Drucker weaves Keller’s prewar life through the novel, a life of health, happiness, and music that inexorably shrinks as Hitler rises to power. Initially, Keller does his best to convince himself and others that the Nazis and their hateful rhetoric will vanish, that “good” Germans like himself will outnumber the maniacs. Though continually confronted by the very opposite, Keller keeps quiet.

When his friend Ernst Schneider is forbidden to perform, Keller is horrified yet inert; Ernst’s teacher intervenes, insisting the young man be permitted to appear. Ernst is granted permission to play one movement of Brahms, which is scathingly reviewed in the Nazi newspaper. Ernst, enraged, threatens to write the paper a letter. Keller, fearing trouble, nervously begs him not to. The men argue. Soon afterward Ernst flees to England, where he writes Keller:

You tried to stop me from writing that letter…it made me think less of you. You were so worried I’d embarrass you in front of the strangers sitting across from us..But what bothered me most was your insistence that since the Nazis don’t have universal support, things will get better. How? How is that possible when they have Germany in a stranglehold?

Ernst closes the letter by ending their friendship. Keller is feels badly, yet simultaneously castigates himself for forgetting to check whether the letter had been opened by authorities.

Then there is Marietta, his fiancée. A Jewish pianist, she carefully plots their escape to Palestine, where the two can marry and work for an orchestra. But when the decisive moment arrives, Keller shirks miserably, missing their rendezvous without a word of explanation.

In Keller, Drucker has created a man in an impossible situation. As a Gentile in Germany, he has a reasonable chance of survival, but only by avoiding any opportunities to help friends and lovers. His behavior, which he carefully avoids examining, make him complicit, yet to act is to risk his life.

While it is easy to condemn this likable, passive man, few of us confront such moral choices in our lifetimes, and can only hope we would act courageously. But many of us would not—we would, like Keller, do whatever necessary to survive. Perhaps we, too, would find ourselves falling silent, retreating to the shadows, as the Keller does. And, we, like Keller, would eventually pay the terrible price of knowing ourselves cowards.

At the camp the Kommandant lays out his plans. He has selected a few Jews for “better” treatment. They are given a bit more food, lighter work detail, separated from the other prisoners. Keller is to play for these living dead, to provide beauty in an effort to reanimate them. The Kommandant, bored with the ease of killing, has turned his interest to reawakening hope in the hopeless. What effect, if any, will music have on these poor souls? Keller is revolted, but must acquiesce or risk arrest himself.

Drucker’s economical prose evokes the horror of German wartime, direct and detailed. Peering into a warehouse, Keller sees “…a thick layer of shoes carpeting the floor—hundreds, no, thousands of them. Leather shoes.“

hen writing about music, Drucker’s spare prose glows. Playing the “degenerate” Hindemith:

It felt wonderful now to forget…and dig into the bold, sharply accented opening movement, to let himself be propelled by its strong rhythmic currents..the thematic material spans two octaves, with outlined triads and fourths vying for supremacy in the atonal fabric.

Over the next four days Keller is shaken from his passivity. His first “concert” goes badly: shocked by his gray, hollow-eyed, emaciated audience, he plays poorly. Initially unresponsive, yet the prisoners soon react strongly to the music, returning to a sort of “life”, Keller, in turn, plays magnificently. We see humanity at its highest—making art—coexisting with our most barbaric impulses. In the novel’s bloody, wrenching climax, all is lost.

While well wrought, the final 30-pages feel rushed, culminating in an anti-climatic ending. We never learn of Marietta’s fate, or even what becomes of Keller, who now understands himself as morally complicit.

It could be argued that the ending, refusing as it does to tie matters up, is successful in suggesting a nation that has lost its humanity and must face the consequences, both on a personal and worldwide scale. But it is also indicative of a flaw in the novel, one that brought Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird to mind.

In this fine, funny novel about writing, Lamott describes working on a manuscript. She’d been sending it to her publisher in portions, and had spent most of her advance, only to receive a letter from her editor saying “I had in effect created a banquet but never invited the reader to sit down and eat.”

While Drucker hasn’t gone quite that far, there could be a great deal more about Gottfried Keller’s complex character as a man, musician, and lover of a Jewish woman he abandons. The camp scenes, particularly the exchanges with music-loving SS guard Rudi, could be expanded. Drucker’s story is a compelling one, and it is a compliment to his abilities that I wished this harrowing book were longer.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)