To the Western eye, few contemporary cities match the exuberance and strangeness of Tokyo’s street culture: Bo Peeps in lacy dresses and aprons, club kids with painted faces and raccoon eyes rimmed with white liner, art students with asymmetrical haircuts and leather jackets juxtaposed with frothy tulle skirts. Several recent books — including 2001’s Fruits, a compilation of photographs from the popular street fashion magazine of the same name, and 2006’s Gothic and Lolita — have introduced these looks to Western audiences, but these have focused on a very narrow window of Tokyo street culture and haven’t explained or given context to the fashions in their pages.

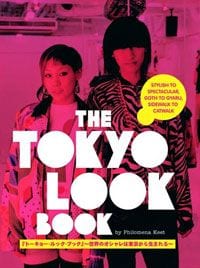

The Tokyo Look Book: Stylish to Spectacular, Goth to Gyaru, Sidewalk to Catwalk, by Philomena Keet and Yuri Manabe, therefore, is an indispensable guide for Westerners interested in Tokyo street style. Manabe’s camera lens captures the city’s most stylish — and outrageous — denizens, while Keet, a British anthropologist who did her doctoral thesis on Japanese street fashion, walks the reader through Tokyo’s various subcultures (and their uniforms) and profiles some of the city’s most influential designers, tastemakers, and boutiques. It’s an entertaining, and certainly informative, book, but it’s ultimately a bit like leafing through a fashion magazine. It’s visually stimulating, but intellectually unsatisfying; its scope is wide, but never deep.

Keet divides her book into five sections: “Shibuya Girls and Guys”, or the trendy teenagers and club-goers (also known as gyaru); “Spectacular and Subcultural”, which includes the Lolitas, Goths, punks, and those who dress up as their favorite anime characters and rock stars; “Youth Street Fashion”; “The Stylish Female”, or the immaculately turned-out professionals carrying monogrammed Louis Vuitton and Gucci bags; and “Young Men at Work”, a broad term that comprises business men, hosts, and construction workers. Keet has clearly spent a significant amount time with each of these groups. She can spot the slightest detail that differentiates, say, a regular Lolita from a Gothic or Pink Lolita, or a yamamba (literally meaning “mountain hag”) gyaru from a joshi kosei (or high school) gyaru. (Hint: yamamba often sport blue or pink locks, while joshi kosei scrunch their white knee-high socks.) The number of terms and sects within sects is overwhelming, but, fortunately, Keet provides a glossary. The reader has a good grasp on each of the sects and sub-sects discussed by the end of each section.

The Tokyo Look Book paints a more complete portrait of Tokyo street culture than previous books on the subject, which often gravitate towards the most outrageous and avant garde fashions. Manabe’s photographs for The Tokyo Look Book, though sometimes out of focus, demonstrate that a woman in a fox-trimmed trench coat and skinny jeans or a construction worker can look as interesting as the teenaged girl in a lace pinafore, dog collar, and plastic Hello Kitty accessories.

Yet despite the wealth of information in The Tokyo Look Book, there’s a disappointing lack of insight. Keet never explains how any of these fashions and subcultures originated. As far as the reader can tell, the gyaru of the Shibuya area have always sported fake tans and frosted hair and their style has barely evolved in the past few decades. Keet mentions the influence of Western fashions on Japanese culture but refuses to explore its impact — what the Westernization (beginning in late 19th century) of Japanese style says about globalization, colonialism, or national pride.

Keet profiles a designer named Takuya Angel whose work examines the dialogue between East and West. He reworks traditional kimonos and accessorizes them with PVC, neon fabric, and furry collars. Angel, at one point, says, “I’d like to remind people of how Japanese society used to be. These clothes are full of my anxieties about today’s society”. Keet, however, never explores this idea or the implications of mixing traditional dress with Western styles in such a jarring, almost disturbing, way. The section on Angel, and various other sections of the book, needs less of Keet the fashion documenter and more of Keet the anthropologist.

Keet also communicates a rather naïve view of fashion and its relationship with status. She writes, “Japan’s attitude towards Western clothes has been unfettered by the accompanying rules of class and status that clothes in Europe have been soaking in for hundred’s of years”. This assertion is difficult to swallow when Japan is one of the world’s biggest consumers of luxury goods — of Louis Vuitton purses, Chanel earrings, and Hermès scarves — the ultimate status symbols.

Conversely, many of the Japanese punks and art students wear Dr. Martens, shoes formerly associated with the working class and, later, adopted by the punk movement in Great Britain. Though Docs have now been co-opted by the mainstream (and are, therefore, more expensive), they still maintain their history and symbolize certain ideals, such as socialism, anti-fashion, and rebellion. It’s unlikely the Japanese are ignorant of the social and class implications inherent in certain Western garments. Whether consumers are consciously or subconsciously buying into these ideas of class and status (or ironically commenting on them), they are still participating in and shaping the historical and social implications in fashion.

This — how street fashion reflects the world we live in (much more than the catwalk ever can), how it constantly tweaks and re-imagines history, how it can symbolize class and status yet can also symbolize the dissolving of class barriers — is what makes street fashion so interesting. It’s disappointing that The Tokyo Look Book doesn’t explore the deeper significance of street culture and fashion in Japan, but it’s the most thorough and comprehensive overview of Tokyo street culture we’ve got. And for many readers, that is enough.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)