Provocative and polarizing, David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) is a spectacle of popular surrealism in which every scene carries with it a duality of spirit. It dares bitter irony and earnestness, whimsical surreality and staunch, ugly realism, deep sensuality and gruesome violence, all in the same frames, the same faces, and the same lines. It’s at times quaint, quotable, and fun, and at others smothered in atmosphere and ambient tension almost beyond description.

Any review of Blue Velvet has to contend with the fact that, being a film as intuitively crafted and enigmatic as it is, each member of the audience will have their own individual reaction to every cinematic gesture on screen. Of course, 33 years after its release and with a monster of a reputation that precedes it, most people already know (or think they know) how to feel about the film, anyway.

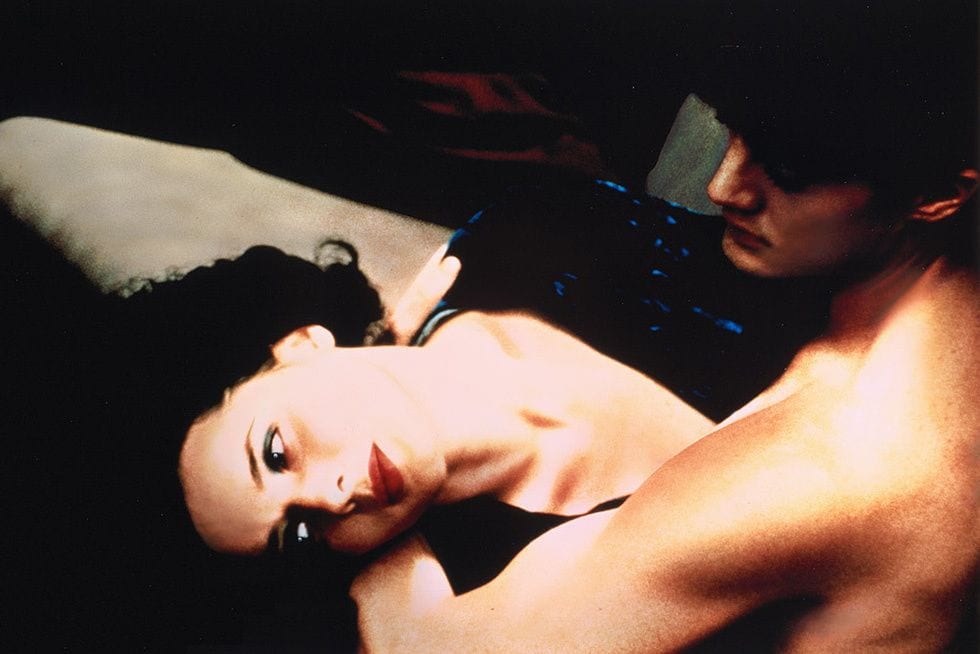

The story is largely auxiliary to the movie’s mood and style, but it sets an important foundation. After returning home from college to visit his hospitalized father, curious and boyish Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) and high schooler Sandy Williams (Laura Dern) launch an amateur criminal investigation of the deranged Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), who has kidnapped the husband and son of lounge singer Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) and forced her into depraved sexual acts. Among the criminal conspiracy surrounding Frank’s entourage and Jeffrey and Sandy’s budding romance, a sudden affair between Jeffrey and Dorothy complicates every interaction and motive.

The story has the narrative beats of a noir and the contours of a psychological thriller, but the film truly has a spirit of its own that isn’t captured by the structural framework surrounding it. Most call it “nostalgic” or “dreamlike”, and for good reason. Set in Lumberton, North Carolina, the America of Blue Velvet is one out of time, rich with anachronisms like classic cars, vintage swing dresses, and early rock ‘n’ roll. The surface of its world exists in the imagination of anyone who has bothered to conjure an idea of the American Dream since the end of the Second World War.

At the beginning of the film, Lynch amuses himself with that puritanical idealism, probing that love for the idea of what America is and all it signifies in the hearts of the zealous with visual gags (firefighters riding on a fire engine in slow motion and waving to the camera, Jeffrey’s mindless preoccupation with striking a glass bottle with a rock in an empty field, etc.) and offbeat dialogue that capture the simple charm of the small-town lifestyle through the happy-go-lucky eyes of its main character. As the movie progresses, Lynch pans away from the chopped lawns and white fences of quiet suburbia, concerned more with the psychology submerged beneath them. By the end, he pulls back to that pristine suburban world again, like waking from a dream.

Using this framing—a delving into and reemergence from—Lynch allows himself the opportunity to explore the ways in which violence, criminality, and trauma touch and shape the delicate world of middle class America. It also gives Lynch the space space to get weird.

In his famously negative review, Roger Ebert branded Lynch’s exploration of small-town life “sophomoric satire”, accusing it of being a simplistic moral tale that engages in bad faith, exploitative mockery of the everyday people on Main Street. But perhaps more than that of any other film, this is Lynch’s world, based partially on personal experiences, and while Lumberton’s quirky surface may seem like shallow surrealism, it’s a surrealism that’s plugged into the Middle-American subconscious—that which lives in the Montana-born director himself—like no other.

MacLachlan’s Jeffrey serves partially as Lynch’s fictionalized surrogate throughout the film, always scrutinizing and inquiring about the mundane and the extraordinary with the same deadpan expressions, but the character’s supposed innocence reveals a lot about suburban attitudes toward the world outside their bubble. Importantly, Jeffrey has no inclination toward preserving his adolescent naïveté; he regards much of the explicit sex and violence he witnesses with the active, unknowing curiosity of a child. Told by Sandy’s father, police detective John Williams, that the department can’t share details about a criminal investigation, Jeffrey tells him “it must be great” to be a detective. What he means is that it must be great to know things, to have your curiosity satisfied, to be an adult and have some stake in life and death. “It’s horrible, too,” the detective replies.

In another scene, Jeffrey tells Sandy, “There are opportunities in life for gaining knowledge and experience. Sometimes it’s necessary to take a risk.” Those “risks” lead him into a maze of vice that enthralls as much as disturbs him. Jeffrey, it seems, is free to blow through the darkness like a tornado, kicking up dust and disappearing back to safety again. He creates the world he wants to see through delusion and separation from the events happening around him; vice and virtue are both available to him at a whim.

The Criterion box characterizes the film as a “vision of innocence lost”, but in Jeffrey’s case, he doesn’t so much lose his innocence as give it up, and by the end, he even takes it back, making for a profound statement on how only people like Jeffrey can take to the taboos of sex, drugs, and murder with the gleeful abandon afforded by the privilege of unaccountability. As Sandy tells him, “I don’t know if you’re a detective or a pervert.”

That isn’t to say that Jeffrey is an irredeemable character, or that he’s entirely clueless about his role in the world. In one key scene, Dorothy desperately coerces Jeffrey into smacking her during lovemaking and it haunts him; he sees distorted visions of both his father and Frank (who fittingly adopts the name “Daddy” during his abusive frenzies), and he cries. The film subtly revolves around the idea of family—the nucleus of American life—particularly the makeshift family of the four main characters, and Frank’s role as the traditional father figure is most pronounced: he has a fixation on dropping the F-bomb, he makes Jeffrey feel his muscles, he has aggressive opinions about beer, and of course, he has a fetish for wielding violent power and authority as a perverse expression of what he might regard as love.

There’s some kind of subconscious fear working in Jeffrey’s relationship to Frank, the dread of “becoming his father”, of perpetuating systems that rely on traditionally masculine traits of possession and dominance and the kind of twisted sense of paternal identity that allows Frank, for instance, to ritualistically rape and terrorize Dorothy, and—on a much smaller scale—allows Sandy’s boyfriend Mike to aggressively confront Jeffrey and Sandy with force near the end of the movie. Jeffrey’s slip into that kind of paternal violence momentarily traumatizes him, even as his voyeurism and exploitation of Dorothy as a subject of sexual fascination—part of the same systems of masculine maltreatment and degradation of femininity—doesn’t. As Jeffrey says, “I’m seeing something that was always hidden,” but he can’t see all of it, let alone understand it. Who can?

The unexpectedly happy ending doesn’t ignore the murky horror of the rest of the film, but accentuates it; perhaps the best way Jeffrey, Sandy, and the rest of Lumberton can cope with wickedness is to ignore it and let it be in the distance, beyond their vision. But the truth they know in their souls is that the security promised by tradition (and represented by the conservative suburban enclaves in the “good part” of Lumberton) is completely artificial; life is millions of volatile forces colliding together, forever creating and destroying in atomic chaos. They may not be able to control it, but they can, in a sense, control their reactions to it.

In that way, the darkness in the underbelly of Blue Velvet is about more than the poison at the root of supposed suburban purity, but more broadly about the cerebral complexes of American psyches, the urge to bring order to chaos and stem the natural entropy of the world, and the ignorance of privilege. But how can we appreciate a film about America’s private darkness in an era when such anxieties, tensions, and corruptions are more openly apparent than they have been in some time? Well, perhaps we can by acknowledging that these problems require solutions, that action is often necessary to confront the things which make us uncomfortable, that we can’t always turn away from the bleak edges of reality. This is true especially now, when the ideal American life, as much as ever, feels like a distant dream.

* * *

In addition to a dazzling new 4K restoration supervised by David Lynch, the Criterion edition of Blue Velvet includes a wealth of surprisingly robust special features. The major highlight is The Lost Footage, 53 minutes of deleted scenes including an extensive prologue that shows Jeffrey’s college life before returning to Lumberton, scenes that expand on sideline characters like Mike and Jeffrey’s elderly Aunt Barbara, and plenty of more aimless and abstract material like a date between Jeffrey and Sandy at a lounge variety show that combines music, comedy, and exotic dance all on stage at once for several uninterrupted minutes.

Also included are two documentaries (one produced in 2019) featuring plenty of cast and crew interviews with behind-the-scenes anecdotes, a reading from the chapter on Blue Velvet in Lynch’s semi-autobiography Room to Dream, and Peter Braatz’s experimental tone piece chronicling the film’s production, “Blue Velvet” Revisited. This is no doubt the most complete and reverential package produced for the film.

- Shadows and Light in the Female Form: On 'David Lynch Nudes ...

- 'Twin Peaks' and Its Twisted Reflection - PopMatters

- Room to Dream by David Lynch (book review) - PopMatters

- What Is Not Erased: Kafka and Lynch and Their Gift of Death ...

- David Lynch: Crazy Clown Time - PopMatters

- An Open Letter to David Lynch - PopMatters

- David Lynch: The Big Dream - PopMatters

- Moving Beyond the Dream Theory: A New Approach to 'Mulholland ...

- Room to Dream, David Lynch (book review) - PopMatters

- Will David Lynch Ever Make Ronnie Rocket? - PopMatters

- The Twisted American Classic, 'Blue Velvet' Gets a Deluxe HD ...

- The 10 Reasons Why 'Blue Velvet' Is a David Lynch Masterpiece ...

- David Lynch's Dark Doubles: A Shadow Journey Into the Heart of ...

- What We Want vs. What We Need: How 'Twin Peaks: The Return' Resists Nostalgia - PopMatters

- Eraserhead's Stylistic Tics Leave Traces of Infection - PopMatters

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)