By marking the perimeters of the acceptable, by opening a threshold onto the chaos of madness and the entropy of unchecked deviance, the freak in Waters’ works performs a social service, thus qualifying its vaunted difference and reflecting society itself in the funhouse-mirror of its own self-obsessions.

The filmic oeuvre of John Waters is replete with oddballs. That’s his stock in trade. Starting off as an independent filmmaker in Baltimore—funded by his parents (he paid them back) and using his friends as his actors—Waters sought to foment outrage and delight from audiences through his ability to make the shocking amusing and somehow invigorating. Although he was often accused of simply displaying poor taste, such criticism is not entirely accurate and far from fair. Rather, he cultivated poor taste. In Waters’ work, poor taste is a manner of refinement that attains a strange air of considered sophistication and knowing advertency. Casual gaucheries would not suffice. Waters’ deployment of deviance is strategic, his vulgarities calculated to make a specific impact that navigates deceptively simple social observations with the acerbic aplomb of an intentionally cheap irony.

His films, particularly the early pre-mainstream works, explore the role of the outsider from the point of view of those insistently proud of their ostracized position, that status of exclusion celebrated as tantalizingly exclusive. Cinderella (Mary Vivian Pearce) in 1969’s Mondo Trasho, attains magical bird feet that instantly transport her to various locations around Baltimore. Lady Divine (played by Waters’ muse, Divine) in Multiple Maniacs (1970) operates the Cavalcade of Perversion, a freak show that includes such featured acts as the “Puke Eater”; she later gets raped by a giant lobster (an outré experience to top all others). In Pink Flamingos (1972), the characters compete for the title of “Filthiest Person Alive”, perform sex acts that include live chickens, tie sausages to genitals, and eat dog feces. Female Trouble (1974) follows the exploits of Dawn Davenport (again Divine) as she descends into the depths of depravity, making manifest a mantra of “crime is beauty”, and attaining fame through gratuitous acts of grotesque debauchery.

Waters concerns himself in these works with the anomaly, the aberration, the oddity, the eccentric, the misfit, the abnormal, the outré—in short, the freak. These are exploitation films to a degree (exploiting the audience’s willingness to view “surviving” a film as tantamount to a badge of honor as much as exploiting the actors’ willingness to play at debasing themselves) but they are also, and more importantly, meditations on the nature of the freak. If there can be said to be some kind of philosophical import to the Waters film, it is this: Waters executes a dialectical examination of the freak through an immanent analysis of the outsider, following its internal movements toward a negative critique of society (that is, an exposition of the intrinsic contradictions upon which society operates), but ultimately demonstrating that the liminality of the freak is an integral part of the social whole. By marking the perimeters of the acceptable, by opening a threshold onto the chaos of madness and the entropy of unchecked deviance, the freak in Waters’ works performs a social service, thus qualifying its vaunted difference and reflecting society itself in the funhouse-mirror of its own self-obsessions. In this sense, Female Trouble, newly reissued on blu-ray by the Criterion Collection, serves as a treatise on the dialectic of the freak and reveals the speculative thought that ought to undergird the peculiar pleasure we devotees of Waters (and other similar filmmakers) find in revulsion.

The aberrant plays a vital role in the way we relate to the world and understand its motive force, its development, its ontology of dynamic Becoming over an ontology of static Being. Indeed, the aberration is the engine behind the Darwinian understanding of evolution; it is the prick that punctures the equilibrium of relatively changeless eras, that ruptures and subverts the plateaus of stability. “Survival of the fittest” on its own is not a catalyst for change. Evolution in its developmental sense requires an anomaly that slips the traces of conformity. Moreover, this Darwinian insight reveals the importance of the individual as the motivating factor in the progress of the whole, for the isolate (the anomaly, the aberration, the misfit) is by definition the individuated, the particular. The sudden veer that marks the evolutionary leap is the byproduct of the one impacting the many. The “freak”, when successful, charts the path of the future of the normative.

Of course, there’s an inherent risk involved. Nature throws forth all manner of aberration and very few instances of the anomalous gain traction. Most are simply discarded as the equilibrium stubbornly resists puncture. In this manner, the misfit of nature doesn’t always blaze the trail of an actualized future, but rather serves as the cartography of potentiality, the map of what might have been but was not.

The art world, in its Romantic-Modernist guise, also venerates the outsider, here touted as the genius. The genius, according to Immanuel Kant, “gives the rule” to art. If art is, for Kant, by definition not nature (that is, it is artificial) and yet seeks to approximate nature in its manner of operation, then the genius is the underlying motive agency that propels art on its way, that guides it on its unchartable path toward a telos that cannot be known or fully realized. But again, caveats abound. The genius in art must break with tradition only to the extent that he (in these accounts, it is almost always a “he”) thereby furthers its trajectory, reinvigorating that tradition rather than annulling it. Critics laud figures like Beethoven or Picasso, crediting them with injecting a new vitality into the tradition to embolden it, not to anesthetize it. Even an Arnold Schoenberg maintains and emphasizes the traditional values of motivic development and formal integrity while breaking with the blandishments of tonality. Artists too far afield from tradition (the Henry Dargers and Harry Partches of the world) remain as intriguing side lights, encouraging speculation into what art might be like if it were to be something else altogether. And yet they perform a vital function; they serve as signposts of the outer limits—still art and yet not quite, recognizable only in their resistance to recognition.

The roots of the freak show go back to the 16th century when people no longer saw physical deformity as the visible manifestation of a deformation of the soul.

Already we can see an internal contradiction arising in the nature of the freak. The freak incites change but for that change to be effective, the freakishness must be absorbed into the operative means of society; that is, it must be added to the “way things go”. If the freak is the catalyst for change then, on some level, it must cease being the freak. On the other hand, the freak serves as the outlier, the limit case that demonstrates the outer border of the sensical, of the recognized. Insofar as it’s recognized as such, the freak is “made sense of” but only insofar as it’s cognized as not quite making sense. The unassimilable freak plays an important role in the structure of society by marking the ends of the territory; its place in society is to be displaced.

Moreover, there is much to be gained by exploring a brief genealogy of the freak in modern western civilization. The roots of the freak show go back to the 16th century when people no longer saw physical deformity as the visible manifestation of a deformation of the soul. Prior to this era, polite society shunned the deformed in fear that the “evil spirits” they embodied might get loose and ravage the bodies of the uninfected. In other words, paradoxically, the advent of the freak show may be viewed as a sign of (circumscribed) enlightenment. These men and women were no longer seen as accursed, but rather as medical and biological curiosities, worthy of examination and consideration. The separation of physical and spiritual beauty was a mainstay of aesthetic inquiry in the 16th and 17th centuries as can be witnessed in the Canzoniere by Petrarch, the sonnets of Shakespeare, and the portrait of Francisco Lezcano, a “dwarf” in the nomenclature of the day, by Diego Velazquez. Velazquez provides an accurate rendering of Lezcano without symbolically belittling him. He strikes a noble pose, occupies the majority of the canvas, and is not reduced to ridicule by exaggerating his diminutive stature.

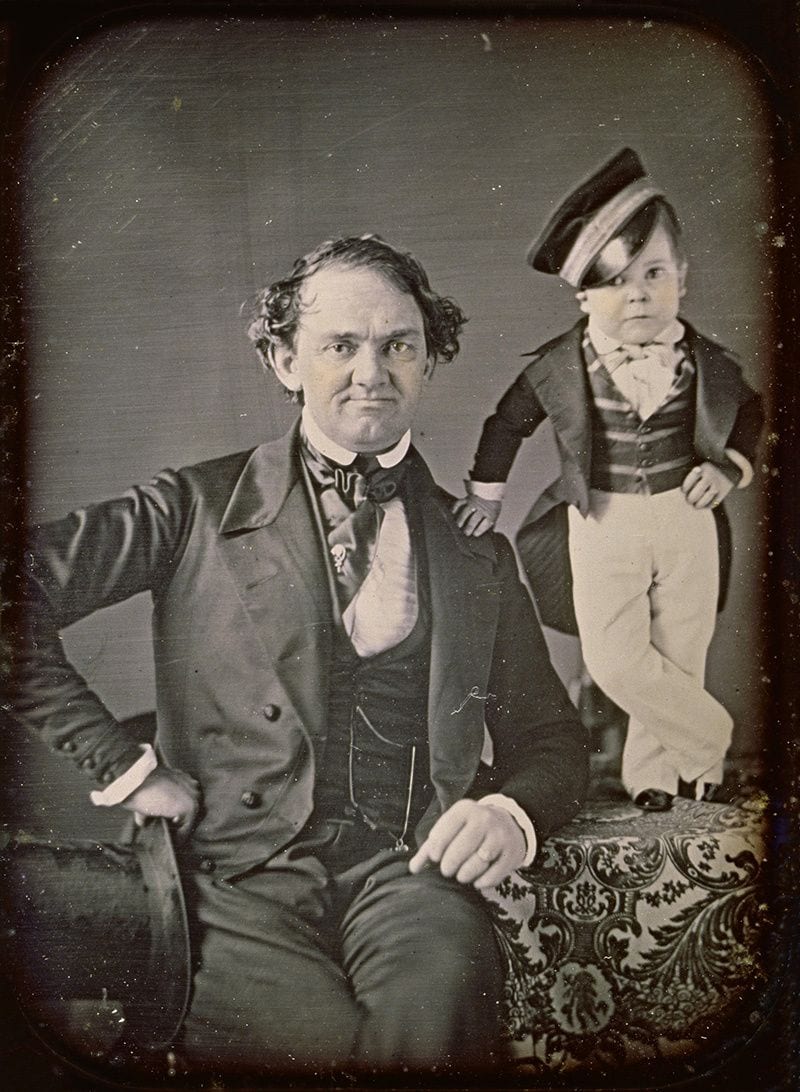

By the 19th century, impressive profits were being garnered by traveling “freak shows” and so-called “sideshows”. Notice the implications of the latter term. These were entertainments that were “on the side” of the main concerns. They were marked as outré, as slightly out of the way. No longer were all of the “freaks” suffering from medical abnormalities (although certain performers were, of course). Certain of the freaks were now self-selecting and were featured because of their peculiar abilities rather than owing to deformity. Sword swallowers and contortionists now populated such entertainments. The freaks, such as the diminutive Tom Thumb promoted by storied manager P.T. Barnum (a distant cousin to Tom Thumb), often became noted celebrities who carefully cultivated their public personae and rigorously separated their private lives from their professional endeavors. The freak show was now a strange and captivating mélange of scientific inquiry and entertainment. And yet the showmen were careful to keep the authority of the medical profession at arm’s length lest a clear diagnosis dispel the mysterious allure of the deformity. If it can be easily explained, it no longer engages the fickle emotion of wonder.

Such films argue that by dismissing the notion of the freak in a reasonable urge to eliminate discrimination, we lose a means of viewing the world that encourages difference, possibility, the unexpected.

At the turn of the century, interest in the freak show declined. They began to be portrayed in the press as cruel exercises in ostracism and degradation. By the time the freak show made its first real foray into film, in Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks, in which a woman feigns romantic interest in a sideshow dwarf in order to bilk him of his money, the public had little patience for such forms of entertainment. The film received a great deal of negative criticism and was edited extensively. It has since emerged as a cult classic and can be seen as the progenitor of a certain approach to film that highlights the possibilities inherent in the position of the radical outsider, the moral codes cultivated by groups largely left to their own devices, and the peculiar prismatic understanding such groups offer of the larger body politic. Such films, Waters’ films prominent among them, attempt to undermine what might be termed the dogmatism of the freak (the notion that any examination of outliers egregiously involves exploitation). Such films argue that by dismissing the notion of the freak in a reasonable urge to eliminate discrimination, we lose a means of viewing the world that encourages difference, possibility, the unexpected. The point of the freak for these works is that it resists conforming to the quotidian notions we employ to make sense of the world.

This makes Dawn Davenport (Divine) a sort of patron saint of freakdom. It isn’t that Dawn wants anything all that different from what a great number of people desire. She wants to be glamorous and fashionable (as a high schooler she insists that she had better get some cha cha heels for Christmas). She wants to rebel against parental authority (in her case, she topples the Christmas tree and then has sex with a random stranger—also played by Divine, who for the remainder of his life enjoyed answering “Go fuck yourself” with “I’ve already done that”). She wants financial success and security; she longs for fame. Dawn differs from most other people not merely in the lengths to which she is willing to go to attain those goals, but more importantly, in the absurdist moral and aesthetic positions she occupies in her understanding of the goals and their place in the world.

Falling under the spell of Donald and Donna Dasher (David Lochary and Mary Vivian Pearce)—the owners of the Lipstick Beauty Salon, a business that carefully selects its clientele based on their penchant for depravity—Dawn espouses the belief that “crime is beauty” and that the further she is willing to transgress social norms of decency and proper comportment, the more beautiful she becomes. At first, this means that the Dashers photograph her in the commission of crimes but when rival Ida Nelson (played with characteristically bizarre aplomb by Edith Massey) hideously disfigures Dawn’s face with acid, the notion of beauty moves toward an equivalency with repugnance. The film continues down the path of this inverted logic to the point that Dawn has her own popular nightclub show where she cavorts in a tub full of dead fish, jumps on a trampoline, and convinces an audience member to allow himself to be murdered by her in his quest for vicarious fame.

Here we begin to discern the dialectical nature of the film’s investigation of the freak. The Hegelian dialectic was developed to free reason from its Kantian bind. Kant held that we could not properly think that which was beyond our conceptual grasp and that there was a sharp distinction between our experience (the phenomenal realm) and things as they were in-themselves (thenoumenal realm). Owing to this division, we can never properly think (or encounter) the particular (what Hegel terms the “unconditioned”—meaning, in part, that we seek to encounter it on its terms rather than explain it away as a result of its causes) because we can only understand items in the world by subsuming them beneath concepts (which have an element of universality to them). Hegel sought a means to escape this bind but without leaping over reason as such. Hegel grounded his attempt in his take on “the concept” (der Begriff). The concept, for Hegel, represents the inner nature of a thing (this is reminiscent of the Aristotelian essence). For Hegel, this concept involves a thing’s inherent movement; the inner nature of a thing drives it toward some end, some telos. In tracing the movement of thought in relation to the concept, one traces the inner movement of the thing in question. An element of that inner movement is the thing’s connection to the greater whole. Many contradictions we encounter in thinking about a thing involve a confusion of level (thinking of a part as though it were the whole).

Female Trouble, indeed all of Waters’s early output, works its way through a dialectical meditation on the nature of the freak. The theses of the film (in both the Hegelian and the quotidian sense) are on the one hand, that “crime is beauty”, and on the other hand, that the freak is a particular (an individual) who is so far outside of the norms accepted by society as to be monstrously self-sufficient. We saw a hint of the latter in the early concern with the freak show itself: showrunners kept doctors at a remove from the performers so that their aberrance would not be explained away as simply another in a series of cases of malady x.To account for the freak in this manner is to erase its radical difference. It continues to occupy a minority position, but is no longer unique, no longer a particular. The edict that “crime is beauty” is equally proposed as a monstrous position, an inversion of our typical understanding of the relationship between immoral legal transgression and aesthetic value. Beauty is attributed traditionally to righteousness, in part, because both beauty and righteousness are seen to possess the trait of “fittingness”. In short, the beautiful is that which is fully formed in the right proportions (the Kantian example is the painting in which there are neither too many nor too few brushstrokes, and in which everything is properly arrayed). Crime, by definition, is a flouting of conventional balance and equanimity. “Crime is beauty” appears to be a contradiction in terms; it stands alone as an edict that fails to comport with our understanding of the world and hence a mere aberration, destined to be dismissed out of hand.

Far from embodying free expression of the self, the social norms of beauty (the emphasis on proportion, profitability, association with certain expectations regarding sexuality, etc.) are among the many fetters of the unfree. In this sense, the edict “crime is beauty” calls to attention the transgressive qualities we attribute to beauty but so rarely find in things deemed beautiful.

And yet both theses are hardly as self-sufficient or as easily dismissed as they first appear. There can clearly be no sense of a freak without a normative realm with which to compare it. But more to the point, neither the category of the freak nor of the normative is nearly as stable as one might innocently believe. Our potted history of the sideshow (our genealogy of the freak) has already demonstrated that. What’s even more intriguing is the lengths to which people go to maintain the category of the freakish. If a doctor explains a condition away as malady x, the person may be unfortunate but is not a freak. The allure of the freak is its particularity, its seeming uniqueness. Hence, the self-identification with freaks on the part of teenagers (think of the television show Freaks and Geeks, but really nearly any form of entertainment involving adolescents as the main characters—a fine recent example is the Netflix show Big Mouth). At that stage of life, so concerned with discovering what makes a person an individual but also (and seemingly contradictorily) seeking a means of fitting into larger social norms, teens cannot help but associate themselves with the freakish—a seeming aberration, always on the edges of belonging. The promoters of the sideshow sought to protect the freak from a reduction to a category because the freak was seen as the preserve of individuality. Thus, the freak embodies a contradiction: it is the emblem of the unique and yet that status precisely depends upon its relationship to the normative.

Beauty obtains within a similar (but perhaps more elusive) contradiction. Kant defines the beautiful, in part, as that which we can grasp adequately with our faculties of imagination and understanding. In essence, we are able to “master” the beautiful object, to take in its various qualities and see how they cohere—even if we are unable to provide a specific category for the experience. Beauty is social in one sense. Kant says that when we declare something beautiful, that declaration differs from calling it pleasant. Something (say dill pickles) can be pleasant to me and I don’t expect it to be pleasant to you; but (at least for Kant) when I claim something to be beautiful, I anticipate and expect your assent. In another sense, Beauty involves not a social decree (thou shalt find x, y, and z beautiful) but rather derives from the functioning of our faculties (faculties that any healthy person shares).

But we don’t “master” the social and we certainly don’t “master” the law. It is imposed upon us. Nor does the law (the social) derive from the common functioning of our faculties. It is imposed in order to maintain power relations (often to our detriment with respect to personal freedom). Far from embodying free expression of the self, the social norms of beauty (the emphasis on proportion, profitability, association with certain expectations regarding sexuality, etc.) are among the many fetters of the unfree. In this sense, the edict “crime is beauty” calls to attention the transgressive qualities we attribute to beauty but so rarely find in things deemed beautiful.

It is this reversal, the realization that the freak is an essential part of a social whole and the realization that beauty falls into contradiction by attempting to be both normative and expressive of individuality (transgressive), that Female Trouble executes in such uproarious fashion. Fame and other social aims depend upon these contradictions: to stand out enough to be noticed and desired but not so much to be reviled. Of course, we all know, as the film demonstrates, that fame often catapults its chosen progeny beyond good and evil. Somehow it comes as no surprise that once Dawn Davenport achieves a kind of fame, that this fame should continue under the force of its own propulsion. Anchoring the whole construct, of course, is the riotous performance of Divine. The manner in which Dawn’s face illuminates with the anticipation of the adulation of the crowd, the sheer glee she finds in posing despite (or maybe because of) the deformity of her acid-scarred face, the grandiose exuberance of her revelry in crime broadcast before a captivated public—all this speaks to the strange contradiction of the freak: we want to be different, we want to belong, we want to belong by being different.

Criterion Collection has recently released a Blu-Ray edition of Female Trouble that returns the film to all its garish brilliance. There are several extras here, including an audio commentary by Waters from 2004; new and archival interviews with Waters, cast, and crew; deleted scenes and alternate takes; and a behind-the-scenes documentary by Steve Yeager. The extras are all mildly entertaining and worth a viewing but the real allure here (as it should be) is this ever-quotable, ever-watchable classic film.

- I Am Divine, Jeffrey Schwartz (film review)

- Love and Frogs: An Interview with John Waters

- John Waters and the Demented Delights of the Demi-Monde

- Short Cuts - Forgotten Gems: Female Trouble - PopMatters

- Filthy: The Weird World of John Waters by Robrt L. Pela

- Carsick by John Waters (book review)

- Low Budget Hell: John Waters' Female Trouble and Cry Baby

- Ranking the Greats: The 10 Best Films of John Waters - PopMatters

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)