The term “barbarian” describes people who are savage, backward, crude and violent, the opposite of civilized and advanced. That was the term the ancient Romans used to describe, in the words of Terry Jones, the “unwashed illiterates” who lived outside the Roman Empire — the Celts, the Goths, the Dacians, the Persians, the Huns and the Vandals.

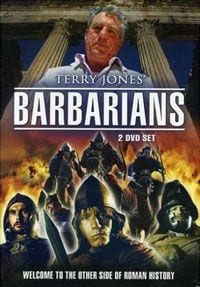

But, argues former Monty Python member Jones in his BBC series, Terry Jones’

Barbarians, the Roman viewpoint seriously distorted historical reality. In his four-part series, which originally aired in Great Britain in 2006, Jones says, “I’m looking for what the Romans didn’t tell us.”

It shouldn’t be a surprise that Jones has turned his intellectual curiosity and acute sense of humor to the study of history. After all, the movies made by Monty Python’s Flying Circus — Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Life of Brian, even episodes from Monty Python’s Meaning of Life — all of which Jones either directed or co-directed with Terry Gilliam, were historical in nature, though the historical perspective was satirical and outrageous.

More recently, Jones has made a series of successful historical documentaries for British television, including The Crusades (1993), Ancient Inventions (1997), Hidden Histories (2002), Medieval Lives, (2004) and The Story of One (2004).

In Barbarians, Jones travels to the lands that had once been conquered by the Romans and finds that the conventional view of history — which usually represents the viewpoint of the victors, not the vanquished — is pretty much wrong. Interviewing historians and archaeologists and examining the existing historical evidence, Jones makes a strong and witty attempt to correct the historical record.

The Celts, for instance, who once reigned from Britain to Turkey before the Roman conquest, were actually “a highly developed civilization” and the “first great road builders in Europe” — an achievement the Romans always claimed for themselves. The Celts developed solar calendars far more advanced than the Romans, mined gold and iron, enabled women to achieve a greater amount of equality with men than existed in either Rome or ancient Greece, and recognized the societal need to care for the elderly, the infirm and children.

But as a loose federation of towns, they could not withstand the onslaught of the Roman army (from 58 B.C. to 51 B.C.). In the estimation of Julius Caesar himself, when the Romans conquered the Celts in Gaul (roughly modern-day France), out of a population of ten million, one million were killed and another million enslaved. So who’s the more civilized?

And so it goes through the succeeding chapters of Terry Jones’ Barbarians.

“The Savage Goths” looks at the achievements of the Germanic tribes who lived north of the Rhine River and whose leader, Alaric, succeeded in “sacking” Rome in A.D. 410 during the Empire’s decline. But, according to Jones, the “sacking” was relatively mild and left most of the city, its people and its buildings intact.

Jones also explores Dacia, in present-day Romania, which the Roman general Trajan brutally conquered in A.D. 106, mostly for the gold found in the Carpathian Mountains.

In “The Brainy Barbarians”, Jones explores the cultural diversity and military skill of the Persian Empire, whose rulers annihilated an invading Roman army led by Crassus in 55 B.C. But he also includes in this chapter the achievements of the great Greek mathematician Archimedes, who lived in the Sicilian city of Syracuse (still a Greek city at that time) before being slain by an invading Roman soldier in 212 B.C., and the advanced Greek city state of Rhodes.

Here Jones is on shakier logical grounds. It’s no doubt true that the Greeks, even during the Roman era, produced more innovations in mathematics and other sciences than the Romans did, but why include them under “barbarians”? It may be useful as part of a general critique of the Roman Empire to point out, as Jones says, that “All the Romans could do was steal (the Greeks’) gadgets and bring them back to Rome,” but that’s a bit off the main topic.

The final chapter, “The End of the World”, looks at the Huns, led by the warrior Attila, and the Vandals, led by Gaiseric, who assaulted the dying Roman Empire from the north and south, respectively, in the mid-fifth century. Jones doesn’t have many positive things to report about the Huns, other than their superior fighting ability and skill at extorting gold from Rome.

But the Vandals were different. Christian but not part of the emerging Roman Catholic church, Gaiseric led his people from central Europe to Spain to North Africa and to Carthage, from where they “vandalized” Rome in A.D. 455. According to Jones, despite their name and reputation, the Vandals were actually more culturally sophisticated, religiously tolerant and less corrupt than the Romans.

Jones’ Barbarians has been criticized by some historians for “cherry-picking” the past – looking for every instance of “barbarian” advancement and Roman backwardness to make his case. And in his zeal to show the accomplishments of, say, Celtic society, he may have underestimated the Celts’ own militaristic tendencies. As historian Susan Wise Bauer points out in her book, The History of the Ancient World:

The world `Celt,’ given to these tribes by the Greeks and Romans, comes from an Indo-European root meaning `to strike,’ and the weapons found in their graves – seven-foot spears, iron swords with thrusting tips and cutting edges, war chariots, helmets and shields – testify to their skill at war.

Still, Jones has uncovered enough fascinating material to justify his main point that the popular legacy of the Roman Empire and its role in the creation of the modern world needs to be re-examined. And that some “barbarians” actually may have been among the most progressive and forward-thinking peoples of their time.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)