In the first third of Kaneto Shindo’s 1960 film The Naked Island, the viewer is presented with an image that seems to have left an indelible impression on my mind despite the fact that Shindo doesn’t call any particular attention to it and despite its relatively inconsequential nature. The image is of a pinecone suspended in the saltwater of the sea as it laps softly at the shore of a tiny island. The water continually pushes in toward the beach but it never delivers its tiny parcel to land. The pinecone bobs within the sea, moving constantly but going nowhere.

That way of phrasing it might make the image appear to connote hopelessness or futility. It does not (at least not for me). Rather it articulates in one gentle impression a central concern of the film.

Water is a troubling element. It simultaneously sustains and threatens life. Moreover, in The Naked Island, water is a two-fold entity. The island is, of course, surrounded by seawater and it is the medium through which one travels to go anywhere outside of the island’s meager circumference. But the island is bereft of fresh water and its inhabitants must convey water to drink and to sustain crops from a neighboring island. Water here is simultaneously ubiquitous and in short supply.

The pine trees, the island’s main vegetation aside from the cultivated crops, require very little water to survive. The pinecone of the image thus is a metonym for the desiccated natural state of this island suspended in saltwater, unable to be delivered from its condition, seeking sustenance from a form of water that cannot provide it. And yet the calm lapping of the water and the mild sway of the pinecone reveals an abiding placidity that underwrites what seems like an impossible tension. Perhaps the greatest achievement of The Naked Island is its ability to employ the form of images as a means of transcending their objective content.

The story behind the film is relatively familiar, at least to those well versed in post-war Japanese cinema. Shindo worked as a screenplay writer for the Shochiku film studio where he produced scripts for most of the directors at the studio (with the exception of the renowned Yosujiro Ozu). Perhaps his finest collaborations were with director Kozaburo Yoshimura. However, the two soon gained a reputation for what was regarded as an overly pessimistic view of life. Therefore they struck out on their own and, along with actor Taiji Tonoyama, they founded an independent film production company, Kindai Eiga Kyokai (Modern Film Association). Shindo now tried his hand at directing films and found some international success with his controversial Children of Hiroshima (1953), the first film to address the US bombing of Japan.

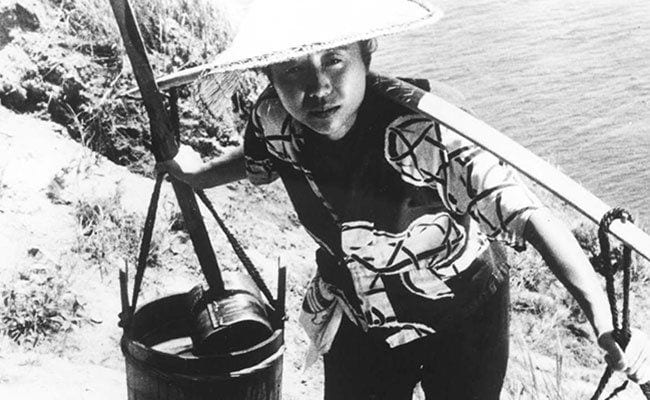

By the end of the ’50s, however, Kindai Eiga Kyokai was in serious financial trouble. Shindo gambled by making what, at the time, he thought might be his last directorial effort: a black and white film shot in a documentary style but with no dialogue and centered on four characters (a mother, father, and two sons) living alone on a tiny island where they labored intensively to raise meager crops of sweet potatoes and wheat.

The Japanese critics and many of his contemporary filmmakers saw The Naked Island as regressive but it garnered international praise and won the Grand Prize at the Second Moscow International Film Festival in 1961. This strange little film, what Shindo termed a “cinematic poem” showing “human beings struggling like ants against the forces of nature” saved Kindai Eiga Kyokai and Shindo’s career as a director.

One can easily understand the contemporary Japanese criticism of the film. If we are to take this small family as the archetypal manifestation of Japanese life, then it appears to be hopelessly, one might even say recklessly, chained to Japan’s agrarian past. There is a striking sequence near the halfway point in the film when the small family travels to a more urban area in a nearby island to sell at market a large fish one of the boys caught on their isolated island. They take a steamship to get there.

They make small purchases of cotton shirts, eat at a restaurant, and gawk uncomprehendingly through a store window at a television screen on which a leotard-clad dancer makes strange faces and poses bizarrely. The family doesn’t seem to covet the material pleasures of modernity; indeed they don’t seem to register any real recognition of them at all.

The members of the family (even the small boys) strike one as totally estranged from the conditions of their time. But once the viewer is alerted to the proximity of technology, the material vestiges of modernity crop up again and again — almost always in the background and often passing quickly from view. There are several motorized sea vessels that move smoothly across the screen while we watch the mother arduously work at pushing her way through the water on her skiff. There are fireworks in the far-off distance (most likely emanating from the market town) as the mother, having recently suffered a terrible loss, stares disconsolately into the distance.

With modern amenities so close at hand, why, one might ask, should a family choose to live under such antiquated and labor-intensive conditions? And yet, it must be emphasized, despite all of the endless toil depicted in the film, the family doesn’t seem to object to the conditions of their existence. They seem at peace, integrated into their agrarian lives, even happy. The work is arduous, repetitive, and ceaseless but it’s depicted not as mechanical or stultifying but rather as human and life giving.

The score, provided by composer Hikaru Hayashi, emphasizes the sense of the permanence of their condition by permeating the soundtrack with variations on the same folk-like tune. But that tune is so serene that it seems to ignore the notion of labor in the film altogether (indeed in the commentary Hayashi insists that he intentionally avoided musically depicting the effort we see the characters making in the images). The music suggests a transcendent tranquility that underlies the grueling work. In a postwar cinema that longed to confront the advantages, dilemmas, and turmoil of the modern moment, The Naked Island must have struck many Japanese critics as a woefully misguided romanticizing of a pre-modern Japan limited by its agricultural economy and social structure.

Shindo seems to have been concerned less with a representation of some archetypal notion of the Japanese spirit than he was with a consideration of the centrality of work to existence. The mother and father employ backbreaking labor to carry water to the parched soil of the island in order to sustain their crops. They methodically pour a small portion of that water onto the earth and the earth greedily drinks their offerings. The earth’s thirst is never slaked. The work is never done, but neither is the growing. And even when the unthinkable happens to the family, it continues as well.

The mother, in what I regard as the highlight of the film, briefly rails against the cruelty of fate by rebelliously emptying a precious full bucket of water onto the ground. She is not watering the plants; she deliberately wastes a precious resource. Earlier in the film, in one of its most critically discussed scenes, the husband struck the wife when she accidentally spilled a bucket. Now he bears silent witness to her act of profligate defiance; his face is calm, accepting, expressing no threat but only sympathy, and reassurance. The wife sobs inconsolably, her tears pouring into the dry soil. Soon she stops, lifts herself from the ground and returns to watering the crops. The work continues.

Work can be seen as mere struggle, a Sisyphean effort that repays nothing. Or work can be seen in the way Shindo seems to see it, as redemptive and transcendental. Work is not about mere achievement (the family doesn’t enhance their condition, they are simply sustained by their effort), it’s not about attaining material wealth (thus, their lack of interest in the wares of modernity). Ultimately, work is not about us at all.

Work transcends our condition. It’s part of our living nature. The sea works to erode the land, animals work to maintain their habitats and their offspring, and this small family works to sustain themselves and their land. In one sense their individual work will end when they do, when the die. Their work, our work will end but work as such will continue as long as there is life.

The Criterion Collection, as always, is to be commended for its presentation of this film. The image of this restoration is gorgeous throughout and Criterion Collection provides a fine essay by curator Haden Guest, an informative interview with film scholar Akira Mizuta Lippit, a commentary on the film by Shindo himself and composer Hayashi, and an appreciation by actor and Shindo enthusiast Benicio Del Toro (who was instrumental in bringing the Shindo retrospective to BAM in 2011). The appreciation and the commentary are perhaps somewhat underwhelming (Del Toro unleashes a string of odd platitudes and Shindo ad Hayashi fail to say much of interest), but the overall package is a welcome treatment of a quietly penetrating film.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)