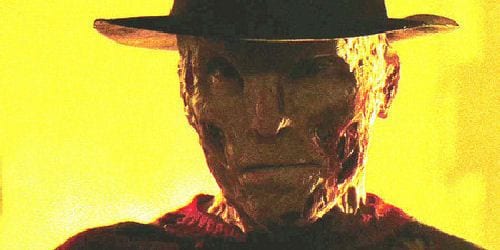

Here he is, teenagers and twenty-somethings. To paraphrase – or perhaps, bastardize – a familiar saying, every generation gets the villain they deserve, and thanks to Michael Bay and the boys, this is YOUR Freddy Krueger. Gone are the days when Wes Craven and Robert Englund turned a child murdering pedophile into a combination killer and stand-up comic. In its place (via the sensational Nightmare on Elm Street remake, now available on DVD and Blu-ray) we have a reflection of the last 30 years in shock scandal society, a molester as monster presence that infuses every sensationalized news story of the McMartin era with a whole new level of adult dread.

In many ways, the new Nightmare on Elm Street is really not made for adolescent audiences. It doesn’t have the ditzy drive of the current horror crop. It doesn’t languish over gore with churlish glee or give into a desire to pour gallons of grue on everything. The kills – some mimicking the original in place and purpose – are handled in a matter of fear fact manner, the minor arterial spray less important than what is suggested by each slaying. In essence, the update is a metaphor for what the entire day care as Devil’s lair meant to an entire community of parents who saw the safety of outside guardianship stripped of its simplest elements. In a world where lifestyle dictated a kind of indirect orphanage, guys like Fred Krueger were the unfortunate tabloid side effect.

This is not Wes Craven’s fiend. This is not the boogeyman ghoul sneaking under a sheet, using his dream world deception to get revenge. No, this version of Freddy Krueger is all about repressed memories, secret caves, and one special girl who made all of his sick and twisted urges come clear. Many fans reacted in shock over how literal director Samuel Bayer took this tone, allowing his villain to do everything short of stripping down and salivating. In the original, Krueger was a criminal, accused of kidnapping and killing children (notice the gap in between the two hideous acts). As a result of a miscarriage of justice, he was set free, allowing the disgruntled parents of the children he targeted to take the law into their own hands.

While the payback premise is more or less the same in the remake, the execution is far more telling. Here, the kids involved are the actual kids Freddy targeted, not the later in life seed of same. Similarly, the parents don’t tell the police about the crimes (under the guise of protecting their sons and daughters, saving face, and recognizing the limits of the law). Krueger leaves town, is eventually tracked, and in an act of brutal punishment, is burned to death by a gasoline can Molotov cocktail. There’s no real feeling of being jilted by the system. Instead, the Elm Street parents are viewed as wild-eyed and maniacal, unwilling to believe the stories their children tell, sickened by the possibility of them being true, and well aware that only the sadistic satisfaction of their bloodlust will cure what ails them.

Of course, the teens themselves are horribly underserved by all of this, becoming one of the new Nightmare‘s biggest sticking points. Critics have lambasted everything about these kids – from the casting to the “lack of characterization” – in there dismissal of the movie. Sadly, they are missing the point. Quentin is a perfect example of why this zombie drone victimology works wonderfully. As children raised by preschools and prescriptions, whose latchkey laments usually fall on the ears of a poorly paid therapist, not an actual biological link, the disaffected Emo glare is so contemporary it stings. Nancy was a heroine beforehand because her character followed standard horror film convention. Now, 30 years later, she’s a lost and lonely outsider who can’t quite figure out why she doesn’t fit in. Then she finds Freddy’s Polaroids…

It’s incredible, when you think about it, a horror movie that doesn’t shy away from the issues its terror suggests. When Michael Myers kills his slutty sister, we don’t get any of the FBI profiler proof of his later butchering proclivities (John Carpenter just made him evil and crazy -it was Rob Zombie that reinvented him as a nu-traditional Dateline headline). Similarly, Jason Voorhees sees his mother beheaded and just goes nuts. Deformed and slightly backward, his desire to murder is merely an offshoot of such overwhelming trauma. But Fred Krueger is a disease. He’s the punchline pervert in the windowless van scanning the schoolyard for likely cuddle candidates. He’s vileness vamped up with an even more frightening prospect – otherworldly invincibility. No matter how hard these guardians try to protect their progeny, Krueger always has a way in – sleep.

That’s why the new Nightmare on Elm Street is a worthy companion piece to the previous incarnations. Whereas Freddy was initially viewed as an easily marketable commodity, sold to grade schoolers as toy, Halloween costume, or any number of “gotta have it” consumer goods, this version is nothing but shock – very real, very recognizable, and very repugnant. If he is indeed a defiler of the young, he has no business being on the side of lunch boxes or hawking sugary candy (ironic). In the past, filmmakers pushed the character into a realm of ridiculousness, turning him into a cruel carnival barker who had a lame one-liner for almost everything he did. By returning to his roots, by reinvesting him with the nastiness that comes with his noxious desires, he’s not only reinvented, he’s reinvigorated.

Still, for anyone who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s, who heard the rumors of day care workers channeling choice children to local Satanists for blood cult death orgies (and even worse…), the 2010 take on A Nightmare on Elm Street is like a fetid primer. It’s the end game of unprecedented hype, a visualization of every psychobabble warning about taking treats from strangers. In the re-stylized Freddy Krueger, we’ve got every parent’s worst concern, every kids most terrifying temptation, and every society’s sordid little secret. Inside every vial of Ritalin, every diagnosis of ADHD and juvenile depression lies the possibility of a seemingly friendly gardener with a penchant to violating the trust of the tots. Argue all you want over how unfaithful it was to Wes Craven’s original. Screed over how lackluster Jackie Earle Haley is in comparison to Robert Englund. The truth is, every generation gets the terror they merit. In 2010, this Freddy Krueger is the one you warrant.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)