Readers may be interested in a different take on the validity of NASA in these times in this review of Orbiter.

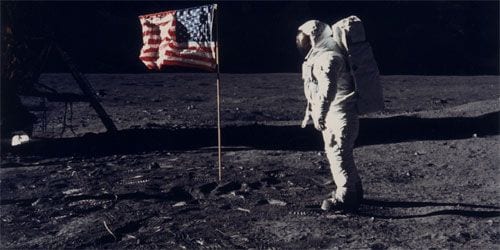

When President John F. Kennedy spoke of conquering challenges and discovering new worlds through the NASA space program in the early ‘60s, his words commanded a sense of determination and patriotism. He believed the moon missions would aid America in ways we couldn’t imagine.

And while President Kennedy was undoubtedly correct in his attitude and assertions during the global space race, it is now a new millennium. New goals have been set along with new priorities when it comes to taxpayers’ money. The good men and women at NASA have concocted plenty of plans for space travel in the 21st century (a moon base, humans on Mars), but save for the International Space Station, none have come close to fruition.

Granted, some of the more expensive endeavors may have been discarded merely because of funding cuts and more immediate concerns for Earth’s inhabitants. Nevertheless, the film fails to elucidate any feelings of loss regarding the lack of recent extraterrestrial explorations.

In 1989, when For All Mankind was released, the Challenger disaster was still fresh in people’s minds and the American peoples’ sense of patriotism was as strong as the economy. Forty years after the first moon landing, Americans have just slogged through eight years of confusion in the oval office and are now facing the trying task of escaping a global recession.

With this in mind, one wonders, when watching Al Reinert’s historic1989 documentary on space travel, what happened to the relevance it tries so desperately to depict.

That said, the film is far from inept. In fact, formally it’s a work of art befitting the historical content its relating. The team at the Criterion Collection has done another outstanding job with its brand new digital transfer. All of the footage is taken straight from NASA, and despite the outdated equipment used during the missions; the visuals presented here are breathtaking. The sound (presented in Dolby Digital 5.1) is also quite good, even if a few mumbled communications require the use of subtitles.

Outside of these formal specifications, however, For All Mankind comes up far short of its potential to make a valid point regarding other-worldly adventure. For some viewers, it may serve as a reminder that there’s more out there than Earthly matters. But for others it will just prove a dreadfully dull, slightly repetitive tale that was much more entertaining, visually stunning, and informative in historically grounded narratives. The film proves frustrating, clocking in at just 80-minutes, in its resistance of any kind of new or unknown information.

In most narrative cinema, the filmmakers try to convince the audience of the events’ accuracy by providing explanations for every aftermath. In For All Mankind, the footage is real and thus apparently warrants no elucidation for any of the amazing events. This theory is simply untrue.

Truth can be, and usually is, stranger than fiction. The audience still needs the “how” to befit the “why”. Their curiosity needs to be quenched. Here, it’s merely dampened. Instead of providing details for how the astronauts survived in zero gravity or what sort of equipment was designed to help them live in space for days on end, we get to watch the astronauts spin a tape recorder again and again and again.

While in 1989 it was certainly cool to see “what really happened” during the moon missions, this is clearly dated, viewers these days want more than just the pictures. I’d have liked to hear some comparisons about space technology, then and now, and to learn more about the now seeming ‘primitive” processes astronauts had to go through to complete each phase of the mission.

Props must be given for following the cinematic standby adage “show, don’t tell”, but a filmmaker (especially a documentary filmmaker) can only take that method so far without leaving out a few fascinating details.

Really, the only viewers who will finish watching For All Mankind and be left without a dozen or more questions rattling around in their heads are the families and friends of the astronauts and NASA officials who starred in the picture (or tech junkies who already know everything there is to know about space exploration). With the ‘60s footage and fixed camera angles, the whole picture has a “home movies” feel to it, but without your Dad sitting next to you and explaining what’s going on as you watch.

The narrators wax philosophical about what it feels like to be in space while their past selves joke around like schoolchildren once they get to the moon’s surface. It’s all very sporadic with the only structure being provided by the three-step process of traveling to the moon (take off, land, and come home). Space nuts may find a few nuggets of information to grasp onto, and it certainly serves perfectly as documentation for a historic event, but For All Mankind doesn’t leave the mark it should or could with those of us with an average level of intrigue for the heavenly body over our heads.

However, in case more than just relatives fall in love with the film, the good people at Criterion have provided a bounty of special features on this single disc release. An Accidental Gift: The Making of ‘For All Mankind’ examines the director’s dedication to the project, and, at more than 30-minutes in length, it tests the audience’s dedication as well.

In case the viewer wanted to hear more ramblings from the film’s narrators, Reinert has also included a few on-camera interviews with a few of the pilots in the segment entitled On Camera. The nostalgia factor is upped with the inclusion of 21 audio highlights many Americans heard on the radio during the space race. These sound clips are actually fairly interesting and a pretty big bonus for space fans who might want to have them at an arm’s reach for years to come.

Paintings From the Moon is an oddly formatted 30-minute segment detailing the work of astronaut post-missions Alan Bean when he took up painting. Bean provides commentary on each entry in his gallery of paintings as it is displayed onscreen. Unfortunately, the artist’s work dwells too heavily on the details instead of the ideas behind each piece that Bean chooses to explain verbally.

There’s also a booklet included with essays from film critic Terrence Reafferty and director/producer Reinert.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)