In 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia was overthrown by a coup whose leaders espoused a Communist cure for the famine and other woes that had beset the country. The government that established itself, called the “Derg”, and led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, quickly revealed itself to be a run-of-the-mill military dictatorship. Three years later the mass killings of anybody deemed a subversive began in earnest.

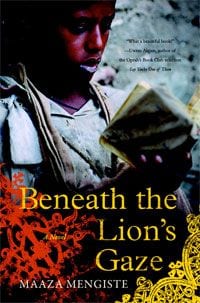

These events make a riveting backdrop to a story and with Beneath the Lion’s Gaze Ethiopian-American author Maaza Mengiste dramatizes this era like an historical novel, using a large cast of conveniently well-connected characters to personify the struggles of a population struggling with revolution, persecution, faith, and rebellion during a tumultuous time. Unfortunately, this book is also popular fiction in the vein of The Kite Runner where moments of insightful characterization and elucidation of a culture and history little known to an English reading audience are crushed by a propensity for broad sentimentality and shoddy uplift. This is a book strong on historical details, but weak in its overall storytelling.

Mengiste opens during the middle of a surgery where Hailu, the patriarch of the book’s main clan of characters, is operating on a boy who has been shot. The details are abstract – “a thin blue vein pulsed in the collecting pool of blood” – while Hailu tries to make sense of how this could have happened to this boy, how this could happen to other boys like his son Dawit, what this means for his country, and how he is supposed to relate to it. He later finds out that the boy has been shot by the emperor’s police and the scene sets the tone for widespread internecine violence that will only worsen while Hailu’s questions about how best to serve his country deepen.

It’s an engrossing introduction to a character and the book’s broader themes, but it is soon diluted by the introduction of an overflowing cast. The reader is introduced to the characters that radiate out from Hailu: his wife, also in the hospital and close to death; his sober, devout Christian son Yonas and his wife and daughter; the spoiled revolutionary Dawit and his best friend, a soldier named Mickey; the family’s friends and neighbors; and historical actors like Selassie (portrayed as a confused and uncomprehending old man) and Major Guddu, the book’s fictional stand-in for Mengistu Haile Mariam. After the coup and the institution of the military dictatorship, these characters are pulled apart in a manner familiar to civil war stories, rebelling against the regime or supporting the government out of fear or greed.

The character transitions that occur in the aftermath of the coup can be clumsily portrayed and obvious. The passionate but impractical Dawit grows up to become a “man” as the mythical resistance fighter “Mekonnen killer of soldiers”, while his earnest girlfriend dutifully heads in the opposite direction as a Communist fanatic that supports the Derg. Mickey becomes Guddu’s right-hand man, a murderer of important men. While Mickey’s development is muddled and a little unbelievable, he is the most interesting character, deeply flawed yet torn between who he was and what he has become. The other main characters, like the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath, move towards moments of Christian compassion and redemption with a saintliness that is too obviously pre-ordained to be dramatic.

Mengiste is good at explaining the details of the historical setting in a way that does not seem forced or intrusive on the foregrounded story. She depicts the passage of time from the coup to the “red terror” three years with succinct breath: “He’d [Hailu] grown weary in those months of jeeps and uniforms, marches and forced assemblies; his patience worn thin from the constant pressure to mold his everyday activities around a midnight curfew. He’d had to contend with identity cards and new currency, a new anthem and even a new flag. He’d come to detest Radio Addis Ababa and Ethiopian Television and the announcements of the arrests and even executions of intellectuals and city leaders, and increasingly, students.”

However in trying to condense action, Mengiste will occasionally lurch the narrative forward with mixed results. It’s effective when she cuts from a scene showing Hailu’s family watching and being outraged by a television documentary about the famine ravaging the countryside to a chapter where the military is escorting Selassie from his compound. Without being told, the reader intuits how that first kernel of outrage at the government’s fecklessness has led to a coup. At times, though, she leaves unexplained gaps in the narration, like how Mickey goes from being a low level soldier who witnesses the arrest and murder of Selassie’s advisers to a vitally important military official. These latter moments give the impression of an epic novel on the cheap, unwilling to devote the page count required to fully flesh out the characters and events.

Likewise, there are strong individual moments of description within weaker overall story arcs. The scenes of the resistance movement in action are sharp with tension. The images of horror — Mickey’s first exposure to the assassination of the government officials and a torture scene with Hailu – are sharp and vivid with the smells and sounds of fear. She describes Hailu’s arrival at a prison with unsettling coldness, “The jail was cleaner than his hospital lobby. It held no smells; there were no noises. Soldiers were attached to chairs, hunched over documents that sat atop perfectly arranged desks, rigid as statues. Not one looked up to take in this latest prisoner, flanked by two of their stern-faced comrades.”

At other times, Mengiste overreaches for easy melodrama when it is hardly necessary given the subject matter. Children are in too much danger in this book, and they are constantly being used for cheap sympathy. Yonas’s daughter Tizita is hospitalized with a twisted stomach and nearly dies in the first portion of the book, and I wondered how overcrowded Hailu’s hospital would get with his family members. Another very young boy named Berhane is coldly tortured and killed by the military and, while I’m sure that such outrageous horrors occurred, the writing of it is gaudy and his death scene borders on kitsch.

The magical mysticism with which that death scene (and the other death scenes) is portrayed is emblematic of the book’s weakest writing, a tendency to dip into maudlin spirituality. Earlier Berhane dreams, “The lion races Berhane over the hill, rushes so fast he feels the wind lifting both of them high above the leafy tree, and soon they are running on clouds. His father barrels across the hill on a white horse, dressed in his white jodhpurs and tunic, a spear in his hand, his hair long and billowing from his head in proud curls.” The flattest character is a medicine woman, kooky and saucy and dressed in black.

It’s within this realm of a uniquely Ethiopian brand of Christianity, combining mythology with the Holy Trinity, that Mengiste’s thematic focus lies. It’s present in the lion of the title, a recurring image that seems to represent both Christ and the good strength of the Ethiopian people. Many of the characters struggle with their religious faith passively and it is only when they are take action that they are able to overcome their fears.

Mengiste ends the book on a note of simultaneous doom and uplift, with the characters and Ethiopia perched on an uncertain ledge, many of them redeemed by their awakened strength through action, but wondering if they will succeed or survive for it to matter. This ending is vague in a pleasantly intriguing way, when everything has previously been spelled out so clearly. By this point, alas, it is too late to redeem what came before.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)