All those cameras,

Taking it all in,

Swiveling from the outer world to peer inside your mind.

“Zap zap jé! º They’re watching us” — among Tibetans this has become a byword, furtively whispered.

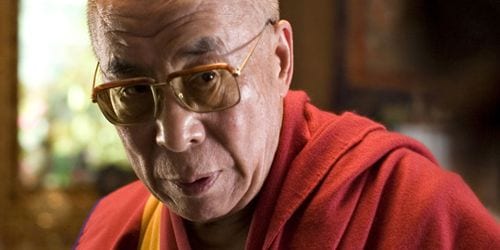

“Just like you need two hands to clap, good will from the Dalai Lama and the exile government alone, without the cooperation of the Chinese, it’s like waiting for their mercy.” Describing the longstanding impasse between China and Tibet, poet Tenzin Tsundue seems at once serene and ardent. Wearing his signature red headband — which he has pledged to wear until Tibet achieves independence — Tenzin Tsundue explains that Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, is possessed of “such an infinite sense of insight and compassion… beyond the capacity of mere humans like us,” who are prone to “get angry, bear grudges, and feel a sense of nationalism.”

Such tensions are at the center of The Sun Behind the Clouds: Tibet’s Struggle for Freedom, at the Film Forum through 13 April, then opening in select U.S. theaters. A leading voice among the Tibetan exile community, Tenzin Tsundue represents what narrator Tenzing Sonam terms the “growing frustration among many Tibetans, especially among the younger generation,” frustration that has evolved over some five decades of struggle. The film traces evolving debates over how best to achieve Tibetan independence, focusing on activists’ 2008 march from Dharamsala, in northern India, to the Tibetan border and the 2008 Uprising in Tibet.

It was no coincidence that the march and the uprising, as well as the Dalai Lama’s stepped-up campaign to raise international awareness of the Tibetan plight, occurred as the Chinese government was seeking to “come out” onto the world stage with the Beijing Olympics. As the documentary notes, public interruptions of the Olympics torch relay — while the “whole world was watching” — helped to publicize Tibet’s struggle. At the same time, as Lhadon Tethong, director of Students for a Free Tibet, notes, the Chinese government sought to “sort of permanently kill the issue” — by agreeing to negotiations and waging its own PR campaign against the Dalai Lama, accusing him of plotting with the West.

The film looks at the tensions within the Free Tibet movement as well, observing the increasing impatience of a younger generation with the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way approach. He submits that Tibet does not want separation from China, but only autonomy, even under Chinese rule. Since 2002, the film reports, the Dalai Lama’s envoys have tried to negotiate with the Chinese, even as the latter has vilified him. The film notes that the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way approach, however ideal, has inspired a strikingly cynical abuse and deceit from the Chinese: it appears that the Chinese endgame is to hold out until the death of this Dalai Lama (he is 74 years old). It has passed a law that all incarnate lamas in Tibet “must now be approved by the state,” in effect granting the government control over the process of finding the next Dalai Lama.

Such legal and political maneuverings inspire more resistance among the Tibetans in and outside of Tibet. The Dalai Lama contrasts Chinese recalcitrance and Tibetan resilience in moral, emotional, and philosophical terms: “China is very powerful but lacking confidence,” he says, “We are very small, but we have confidence.” At the same time, it is clear that the impasse is increasingly untenable for all sides, as multiple positions are staked out by representatives of both nations. (Indeed, as recently as 10 March, the public debate escalated, when the Dalai Lama accused the Chinese government of trying to )

Historian Tsering Shakya frames the Dalai Lama’s own embodied tensions. “One the one hand,” he says, the Dalai Lama is “leader of the Tibetan people. On the other hand, he has a moral position as a Buddhist monk and Buddhist leader.” The first role assumes a responsibility to a people long oppressed (some one and half million have died in the half century’s struggle), while the second demands that he adhere to spiritual tenets, including patience, understanding, and generosity.

Time is a factor beyond the Dalai Lama’s aging, specifically in the changing demographics of Tibet. As more and more Chinese move into the country, the Tibetan population decreases. Poet Lhasang Tsering observes that efforts to maintain Tibet for Tibetans are approaching its own sort of crossroads. Soon, it will “no longer be realistic for the Tibetan people to regain Tibet for Tibetans,” he says. “What has happened to the Native Americans or the Native Australians is happening in Tibet.”

Former prisoners like Rigzin Choekyi make this crisis especially vivid. She describes her torture at the hands of Chinese authorities, revealing how resistance can be inspired rather than stamped out by abuse: “I fainted with the pain,” she says of an electric prod applied to her body and inside her mouth (“It felt as if all my internal organs were burning”). Imprisoned when she was just a 20-year-old demonstrator, she says, “I feel those were my best and most meaningful years.”

The Chinese poet and activist Woeser (Öser) has also taken up the Tibetan cause. Forced to leave Lhasa after writing sympathetically about the Dalai Lama, she now lives in her own exile. The threat of oppression is material and political, she says, but also existential. “The eventual consequence is likely to be that there is no longer a ‘you’ left. ‘You’ will vanish in the end.” Even as this applies to those who are oppressed and negated, it might also be a way to describe their abusers.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)