“It was a time when people loved marketing,” says Mary Wells. “They got it. They understood we were all having fun with each other. Life was suddenly perky.” In its golden age, she remembers, advertising constituted a world of wonder, where ideas and money weren’t antithetical. It was a time, according to Art & Copy, when “people” appreciated pitches for Volkswagen and Samsonite. Other people — or perhaps they were the same people — spent long hours conjuring those pitches. It’s not completely clear whose life was “perky.”

This good time was the result of any number of forces, including an increase in consumer spending capacity after World War II and an increase in advertising venues (say, television and highway billboards). It may also have been a function of what Jim Durfee remembers as change in working conditions. No longer were advertising agencies an “old boys’ club” premised on who knew whom, perpetuating “ingrown mediocrity.” Instead, it was a time of blossoming energies, when forward-looking agencies like his (Carl Ally Inc.) started “putting the art director in the same room as the copywriter: that had never been done before.”

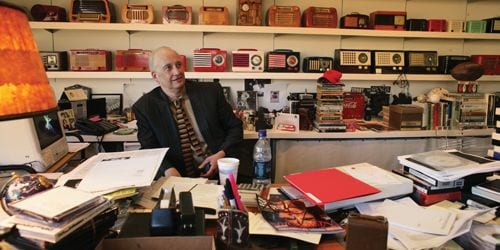

Advertising innovators remember this blossoming for Doug Pray’s 2008 documentary, which premieres 26 October as part of the new season of PBS’ Independent Lens. At times, Art & Copy itself resembles fine advertising. It’s good-looking, persuasive, and nostalgic. Do you remember “I ♥ NY”? Do you long for the days when you were encouraged to “Think Different” or sympathized with the guy who lamented, “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing”? Then the film may be telling you a story you’ve heard or at least intuited before. It reaffirms a sense advertising used to be fun and creative and clever. Now, poor us, it’s just repetitive, lazy, and everywhere.

As the film draws comparisons between then and now, it’s clear that then is much preferred. If Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign was elegant and smart (and enduring: see LeBron’s latest version), today’s marketing is mostly crass, even repellent. The advertising “people” in Art & Copy see themselves as rebels: they surfed as kids, they studied art, they resisted formula. They brought out the best in clients (Tommy Hilfiger gushes that George Lois’ campaign actually inspired him to make better clothes: “He turbocharged my success and then it took off”). They told stories in commercials, and sometimes, they didn’t even show the product in a spot. They remember the 1984 Apple ad, the one that ran one time only, during the Superbowl, with reverence.

In seeking to reflect “people’s lives in a way that touched them,” they didn’t kowtow to obtuse or shortsighted clients, but instead considered — and “knew” — what consumers wanted. Advertising was an exciting field that encouraged originality. “I think what you can do,” says Wells (who worked at Doyle Dane Bernbach before she founded Wells Rich Greene), “is manufacture any feeling you want to manufacture.” It was a field where talent and insight were factors in success. She goes on, “I was born with a gift for sensing what it is that will turn you on.” Jeff takes it another step, seeing his work as a means to create not just desire but also, a sense of community. “I make stuff,” he says, “I put it in people’s faces. It changes them and it’s really a rush to have it happen to millions of people at once.”

It’s an admirable ideal, that ads might achieve goals beyond making money for companies who hire the ad companies. And sometimes, as in the case of Wieden+Kennedy’s campaign for Nike in 1995, including the “If You Let Me Play Sports” TV spot, such a goal seems explicit. Following this ad, the film includes a short series of women-on-the-street interviews, testimonies to the ad’s effectiveness. Girls (and everyone else) will be better off, the campaign argues, if they play sports, and oh yes, purchase Nike gear.

The film opens and closes on Chad Tiedeman, a billboard rotator. Each day he goes out on the road to change the images on billboards. It’s a job his family has performed for generations, “since 1930-something,” says Tiedeman. “I’ve never been out of work,” he adds. As the camera looks up at Tiedeman on the job, the billboard frame majestic and angular against a blue sky. “I don’t know any of the people who make the ads,” he observes, “Not personally, no.” With this, Art & Copy briefly indicates that the creativity of ad people is not directly connected to labor or even to consumption. While the conjuring and promoting of ideas can be exhilarating, the process of advertising is also, always, about making money.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)