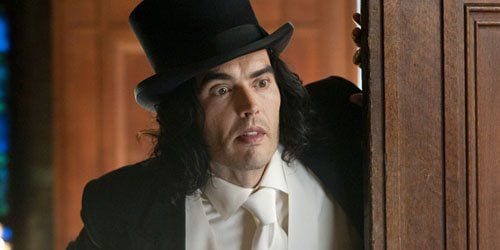

In Arthur, Russell Brand plays a motor-mouthed, devil-may-care addict who also happens to be worth nearly a billion dollars. Indeed, Arthur Bach seems like the perfect role for a motor-mouthed, devil-may-care comedian. If he’s not so wealthy as to be able to buy famous movie cars (the Batmobile, the DeLorean from Back to the Future) so he can drive them around Manhattan, he is famous and rich and has had his own well-publicized bouts with substance addiction.

Yet, compared to Brand’s previous film work, which has consisted almost entirely of his vaguely autobiographical Aldous Snow rock-star character from Forgetting Sarah Marshall and Get Him to the Greek, his take on Arthur feels sanitized, as well as cutely customized to fit the pattern of arrested-development males so popular in recent comedies. This Arthur is, of course, a remake of the 1981 comedy starring Dudley Moore as the drunken billionaire, and what once may have been described as boyish is now, at times, downright childlike.

This childlike behavior is meant to be part of Arthur’s charm, but it’s more like a gesture toward a character, less fully formed than cobbled together. Arthur is part juvenile (with his Batmobile and unchecked appetites), part Russell Brand persona (with his stream-of-consciousness wordplay and musings about how he doesn’t trust horses), and part eccentric shut-in who seems to have never been to Grand Central Station.

These bits of personality zigzag at cross-purposes, like Brand’s talk-show conversational style but less amusing. As a result, the movie’s laughs — and there are some — feel stray and disconnected. Brand is at his best offering the kind of bizarre self-commentary you might recognize from his awards-hosting gigs on TV. But here his asides only boost the distance between him and the rest of the film: “I’m in a chase!” he exclaims at one point, and yes, he is. Scene after scene consists of Brand playing off one cast member at a time, in a plodding rotation that grows wearying.

Some of these scenes involve his faithful, long-suffering, sometimes acid-tongued nanny Hobson (Helen Mirren, gender-switching Oscar-winner Sir John Gielgud in the original part). Others pit him against Jennifer Garner as Susan Johnson, the chilly executive whom Arthur’s mother (Geraldine James) wants him to marry in order to maintain his inheritance. Garner has one funny sequence where she out-drinks Arthur and shows up at his doorstep, giving her the opportunity to cut loose. But otherwise, Susan is only villainous, though not quite as inconsequential as her grumbling father (Nick Nolte).

Amid the wan sideshows, Brand does almost connect with one costar. As in the original, Arthur meets a poor girl from Queens, here called Naomi (Greta Gerwig) and given the movie-friendly ambition to write children’s books. She receives, we’re told, life-changing encouragement from Arthur regarding her writing. As played by indie heroine Gerwig, Naomi’s a sleepy-eyed and not-so-manic pixie dream girl, almost movie-star radiant, in an offhand sort of way.

Briefly, Naomi’s relationship with Arthur has a nice symmetry: he uses Manhattan as an expensive playground, while she, conducting unlicensed tours for her day job, tries to find city magic on the cheap, showing Arthur that fun can be had for free. But this contrast is never fully explored, because the movie can’t quite decide whether to see Arthur’s rampant spending as lovable whimsy or a pathetic, wasteful cry for help. Eventually, it seems to conclude that his bad behavior is both — not as a nod toward complexity, but because it needs Arthur to seem both redeemed and fun-loving.

The same is true of this incarnation of Arthur. It’s little bit fun, but also a little bit apathetic. Arthur’s alcoholism is no longer the broad joke that it could be in 1981. Now it seems incidental; Brand is such a loose-limbed goofball that his moments of drunkenness and lucidity are difficult to parse. For all of the verbal jokes about his wild shenanigans, Arthur never seems all that interested in his many vices, at least not with the debauched commitment of Aldous Snow in Get Him to the Greek, which better showed off a rich man’s heedless pleasures and the pain behind them. What might have seemed ingenious casting on paper is on screen just redundant.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)