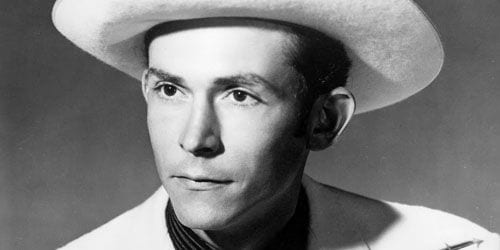

It’s hard to overstate the influence of Hank Williams on popular music. As Bob Dylan said on his show Theme Time Radio Hour, “One of the greatest songwriters who ever lived was Hank Williams, of course. Hank could be headstrong and willful, a backslider and a reprobate, no stranger to bad deeds. However, underneath all of that, he was compassionate and moralistic.” He was also one helluva singer: “The sound of his voice went through me like an electric rod,” is how Dylan put it in his memoir, Chronicles, Volume One. Like Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, and Woody Guthrie, Williams’ impact transcends musical genres and defies easy description: His records are straightforward and colloquial, as far from Dylan’s frenzied, explosive lyricism and thin wild mercury sound as an Ansel Adams photograph is from a painting from Picasso’s cubist period. But what all those artists share is a raw honesty: Their work favors emotion over polish and sees beauty in imperfection rather than perfection.

I consider myself a Hank Williams fan, but not a fanatic, which is to say that way back when, I bought a copy of the three disc Singles Collection but not the ten-disc set The Complete Hank Williams. I love Hank’s emotionally direct songs and his high lonesome singing, but I don’t need to hear multiple versions of the same song, and I’m not afraid of missing something essential if I don’t hear every note he ever sang. So keep that in mind — while I find the new three-disc set The Legend Begins an engaging and generally enjoyable collection, I don’t expect to listen to it again any time soon. The songs are great as ever, and Hank is in fine voice throughout, but what makes the set special — the fact that it consists mostly of old radio shows where Hank played his songs live — is also what makes it less than ideal: The between-song chatter and intros and outros are interesting as nostalgia, but they also interrupt the flow of the music.

The first two discs of the set come from the 1949 radio program The Health and Happiness Show, sponsored by Hadacol, an alcohol-based cure-all that was used as both a laxative and a substitute for whiskey in dry counties in the deep South. The shows sound good, but they’re arranged more in the form of a historical record than a musical one, favoring completeness over judicious editing. Since there are eight episodes here, for example, we get eight different versions of the show’s theme song, “Happy Rovin’ Cowboy”, which is about seven too many for this catchy but insignificant track. Ditto fiddler Jerry Rivers’ signature tune, “Sally Goodin”, and the between-song patter, which sounds like outtakes from Hee-Haw without the attempts at off-color humor.

Still, there’s plenty of great music here, including versions of classics like “Lovesick Blues”, “You’re Gonna Change”, “Lost Highway”, “Wedding Bells”, and “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”. There are also a few tracks featuring Williams’ wife, Miss Audrey, and some gospel-tinged numbers such as “When God Comes and Gathers His Jewels” and “I Saw the Light” that are normally associated with his Luke the Drifter persona. All this music is terrific, but the arrangements closely follow the template of the originals, and only the most discerning Williams followers should expect to detect significant differences.

Disc three — which, I suppose, accounts for the title The Legend Begins — features a pair of songs recorded in 1938, when Williams was 15 or 16 years old, and four more from 1940. The first two, “Fan It” and “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”, sound like the primitively recorded acetates they are. The quality of the 1940 tracks is a little better, but the music is the sort of apprentice work you’d expect to hear from any young country singer and give no real hints about the brilliance to come.

The collection concludes with a 1951 broadcast for the March of Dimes, with Williams and Miss Audrey singing a few numbers and speaking from the heart about infantile paralysis, or polio, and their concerns for their own son, Hank Jr. Like the rest of this set, it has value as history or nostalgia, but does nothing to alter Williams’ legacy. Get it if you’re a completist, or if you want to hear what passed for entertainment on post-WWII radio, but if you’re looking for Hank Williams at his best, you’re better off looking somewhere else.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)