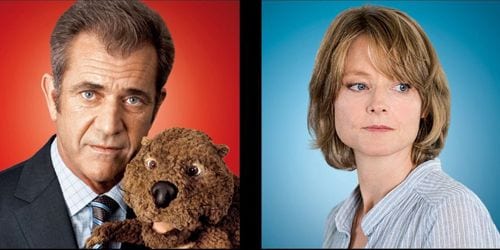

The Beaver tells a story about men who have lost their voice. Its protagonist, Walter Black (Mel Gibson) is facing a depression that has seeped into every aspect of his life. When we first see him, he’s lying on a pool floater. Empty eyes looking up — waiting for answers to drop from heaven perhaps — his body merely drifting as the water does its job. With a sly use of imagery, director Jodie Foster lets us know that Walter is in limbo. An invisible narrator provides whimsical bookends to the film and at the beginning informs us that Walter’s emotional state is worse than it’s been in the past.

His wife Meredith (Foster) asks him to move for the sake of their sons: Porter (Anton Yelchin) and Henry (Riley Thomas Stewart) who are being affected by his barely there presence. Walter moves into a hotel where he finds a beaver puppet in a dumpster. With reasons until then unbeknown to us, Walter takes the furry creature to his room where he tries to kill himself. After waking up the next morning, not only has Walter failed in his attempt to terminate his life, he’s also been taken over by the beaver, who commands him to wake up and do something to fix his life.

Even if this premise sounds almost too fantastic, we are never victims of any tricks by part of the director. From the get-go we know that Walter is the beaver; we see his mouth move as the puppet talks and he never bothers in acquiring any ventriloquism techniques. As he tries to reenter his former life with his family and at work (he is the CEO of the ominously titled JerryCo toy factory) he lets everyone know that the puppet is a tool devised by an expert therapist. Walter can communicate through the puppet and avoid facing people on his own. To everyone’s surprise, the beaver works and Walter’s life begins to thrive, but only for as long as he uses the puppet.

Parallel to Walter’s story we witness the trials endured by Porter, a high school student who has become so worried about becoming like his father, that he keeps a detailed journal — by way of OCD infused Post-Its — of the things that make them similar. In school, Porter’s life is not so different than his father’s. He has become an expert ghost writer who can tap into his classmates’ voices in order to write their papers and essays. Like his father, he becomes so lost within the characters he’s playing that he no longer has an identity. That the film never stresses this out is testament to the loving qualities with which Foster approaches the material.

Once the hottest screenplay in Hollywood, Kyle Killen’s manuscript for The Beaver made the rounds all over the industry, with some of the most respected auteurs putting their eyes on it. Its production materialized only after Foster (who had been working on yet another legendary unfinished opus for years) decided to ask her longtime friend Gibson to play the leading role. Gibson, who has fallen into infamy after his bigotry and domestic violence took over the reins of his career, gives perhaps the greatest performance of his entire career, making Walter someone we can empathize with. His moving portrayal of a man who has lost it all leads us to wonder if The Beaver is acting as Gibson’s own beaver. The tenderness achieved by his now rugged expressions should overcome any doubt that beneath the scandalous public persona lies a man with real talent.

Of course to ask this of audiences who have learnt to judge an artist’s work by their personal lives, might sound like an extreme request. This explains why the film was a box office bomb during its theatrical release and maybe why this DVD release is so light on bonus supplements. The ones included are run of the mill features like a couple of deleted scenes and a behind-the-scenes featurette where everyone praises Foster and evade the deeper repercussions of the movie and its meaning.

The Beaver could very well be studied for its remarkable use of language and the essence of the signifier. We ask ourselves for example, why is it that the screenwriter chose an animal that also has become vulgar slang for women’s genitalia (any Google search with the film’s title will lead you to hundreds of jokes). Because beyond its exploration of depression by way of a Harvey-like redux, this film also becomes a remarkable study about the role of gender roles in our society. The vice-president in JerryCo for example is played by a woman (the magnificent, but greatly underused Cherry Jones) who we’re told is much more talented than her male counterpart, but was snubbed when the time for promotions arrived.

Beyond this there’s also a complex relation between Walter, his son. and the way in which Meredith becomes a channel for them to express their repressed masculinity. She is given the power role without asking for it and when the time for accountability arrives she is then reduced to what society has told us women should do for their men. It’s truly a shame that The Beaver wasn’t more appreciated upon its release, because the dichotomy between extreme realism and whimsical magic that it achieves surely make it one of the best releases of 2011.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)