Is this the real life?

Is this just fantasy?

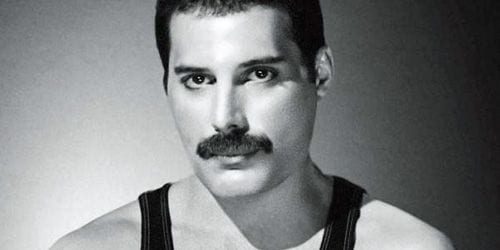

More than just quotes from the lyrics of Queen’s “‘Bohemian Rhapsody'”, these are pertinent questions as one considers the late Freddie Mercury upon reading Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury by Lesley-Ann Jones. Any biography written many years after the death of a public figure is going to be problematic, particularly so when the subject was a (somewhat) closeted gay man keeping his true self hidden from an adoring global public. But Mercury mostly gets it right in a book that tells the story of the life and tragic death of the larger-than-life frontman of mega-band, Queen.

Most rock bios tend to be one of three things: ghost-written autobiographies, journalistic warts-and-all accounts, or friend/lover/employee of the band chronicles. Mercury is a curious mixture of the latter two. Jones is a long-established music journalist, but she also clearly spent a sufficient amount of time with the band, and Mercury in particular — enough to develop a personal relationship.

The result is a book – an update of a biography Jones wrote in 1997 called The Definitive Biography of Freddie Mercury – that is thoroughly researched and reported, and at times very revealing, but that also has a sanitized quality to it. Jones presents the general sordid details of Mercury’s personal life, but it’s often in a euphemistic, nudge-nudge sort of way.

One point aggressively driven home is that Mercury struggled mightily with the balance between his conservative upbringing, his entry into rock ‘n’ roll stardom, and his closeted homosexuality. Born and raised in the British territory of Zanzibar (now Tanzania) in East Africa, Mercury grew up in a strictly religious household. When he was seven, he was sent, by himself, to a boarding school more than 1,000 miles away outside of Bombay, India, an experience that Jones repeatedly describes as highly traumatic. In a way, however, this struggle may have been fortuitous because it led an otherwise introverted and shy boy to find comfort in the admiration of others and in the arts.

At St. Peters Boarding School, Mercury discovered and fell in love with music and applied himself to learning multiple instruments, beginning with the piano. He remained in India until the age of 17, when he finished school. Soon after, he moved with his family to Middlesex, England, and Mercury became an art student at Isleworth Polytechnic in West London.

As he entered his 20s, Mercury played piano and sang in a succession of patched-together bands. During this era, Mercury met guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor, who played in a semi-successful band called Smile. In 1970, the three decided to join forces as the band that became known as Queen, a name chosen by Mercury despite the reluctant chagrin of the other two.

After adding bassist John Deacon in 1971, Queen went on to release three moderately but increasingly popular records while building a reputation as a killer live act. In 1975, the band released A Night at the Opera, the most expensive album ever produced to that point, which featured Queen’s biggest hit, “Bohemian Rhapsody”. It was this album and this song that launched Queen into the musical stratosphere of fame and fortune.

Mercury devotes a solid amount of time to “Bohemian Rhapsody” but it’s mostly just various people commenting on how historic a song it was. And it is an amazing song – it’s almost dumbfounding to think that a song like that could remain at #1 for nine weeks, as it did in the UK. But as to what inspired Mercury to write such a song and, for example, add that middle section with all the repetitions of “Figaro!”, is glossed over in favor of long quotes about how revolutionary it was.

At this point, Queen became a universally beloved band, and during the next few years, Mercury and his bandmates were truly at the apex of rock ‘n’ roll fame. They continued at this level of stardom until the early ’80s, when the hits cooled. It’s interesting to note that in Mercury, Jones doesn’t mislead the reader about their waning popularity but she certainly glosses over it. The fact is that by 1982, Queen’s popularity had ebbed significantly in the United States, and they had become, not a joke, but almost a novelty.

This all changed in the span of approximately 25 minutes on the afternoon of 13 July 1985, when Queen performed in front of 72,000 people at Wembley Stadium and a television audience of almost two billion for the Live Aid benefit. This performance was, and still is, widely regarded as the best set of the Live Aid extravaganza and has frequently been called the greatest performance of all time. Queen was back.

Or was it? The band did release another successful album, A Kind of Magic, and had an enormously successful tour of Europe in the summer of 1986. But the final show of the tour, at Knebworth Park in front of 120,000 people, was the last show Queen would ever play with Mercury. There were more Queen albums and two solo Mercury records, but at this point the story sadly slides into the next phase of Mercury’s life, where he contracts, suffers from and dies from AIDS.

This segment of the book is heartbreaking and very moving. Jones provides extensive detail (mostly via quotes from insiders and observers) on how his life changed and how he was forced to draw in the reins of his jetset life as the disease slowly consumed him. Jones seems as much at a loss as Mercury’s fans as to why he kept his secret – of his homosexuality and his condition – up until the day before he died on 24 November 1991. She quotes numerous friends who said he couldn’t bear to have his conservative and religious parents know about his homosexuality. But the question of whether it was Mercury’s responsibility or moral impetus to alert his fans or the public about the harsh realities of AIDS, during a time when people with AIDS were highly stigmatized in the West, is avoided.

Jones, who claimed to have “toured widely” with the band, does bring a journalist’s knack for collecting the perspectives of those around Mercury via interviews (or other press – there are critiques of her book saying that she merely compiled quotes from elsewhere). The problem is that there are seemingly entire pages filled with the long-ago observations of random passers-by. This can be interesting and insightful, but ultimately do we care what the bass player for a band that opened for Queen on one of their many tours thinks? This kind of reportage occurs so frequently, and often with no clear idea of why this person is qualified to speak for so long, that it starts to feel like too much padding. There’s also far too little perspective provided by Mercury’s bandmates and family, leading the reader to wonder if Jones took the easy road by quoting those who would leap at the chance to be interviewed for, well, anything.

It’s also quite easy to notice the point in the book where the tone shifts from a reporter covering a band to a woman feeling a matronly love and sympathy for a needy and ever-weakening man, the timing of which coincides with Jones developing a close friendship with Mercury. This leads to the constant and almost oddly persistent identification of the title subject as “Freddie”. I suppose it would feel odd for a long-time friend to refer to him as “Mercury” but it’s another ding in the credibility of the author and continues the debate of, what kind of book is this?

Jones has almost a patronizing view of Mercury, and her descriptions of him and his activities are almost childlike. She describes a house’s decorations “which Freddie coordinated all by himself” and people are often “presenting a variety of options from which Freddie could choose.” And the way in which she dismisses Mercury’s frequent petulant behavior sounds much like a mother defending her bratty child.

In the end, however, the reader comes away from Mercury having a solid grasp on the history of Freddie Mercury (less so on his band, but to be fair, that’s not the book’s subject), how his childhood strongly influenced his later years, how his time at the pinnacle of fame changed him, and how he died in agony at the age of 45. It feels more like a VH-1 ‘talking head’ history than, say, a History Channel documentary, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that Jones has penned a relatively thorough and creatively sourced account of Freddie Mercury’s life.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)