After the crossover came the buddy comedies: once Jackie Chan established himself as a viable name in the US with the re-release of Rumble in the Bronx and other older titles in his catalog during the late ’90s, usually via genre-friendly New Linea and Miramax, he was adopted into US action-comedies. Rush Hour, which paired him with fast-talking Chris Tucker, turned his first major US film appearance since his cameos in the Cannonball Run movies into a surprise hit; two sequels followed.

But as popular as the Rush Hour movies were, they never really felt like proper Jackie Chan vehicles so much as his guest appearance in an American action movie: his comic athleticism served as a spice for Chris Tucker’s amusing if familiar motormouthed shtick. The Rush Hour movies are unmistakably made from the Tucker character’s point of view. Rush Hour did establish Chan as a viable buddy-action option, though, which led to Shanghai Noon (2000) pairing him with Owen Wilson, himself a frequent buddy-comedy participant, teamed with the varied likes of Vince Vaughn (Wedding Crashers; The Internship), Ben Stiller (Starsky and Hutch), and Eddie Murphy (I Spy).

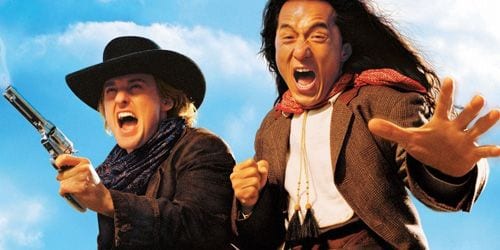

Shanghai Noon and its 2003 sequel Shanghai Knights have arrived together on a single-disc Blu-ray, and though they’re not as fleet-footed as Chan’s best Hong Kong features, they’re probably his most successful American-based productions. Both are rooted in Chan’s point of view, both beginning with lush historical prologues in China: Chan plays Chon Wang (said out loud, it’s a homonym for a famous western personality), a member of the Chinese imperial guard in the late nineteenth century, who travels to America to pursue the abducted princess (Lucy Liu) he fancies. There he meets hapless outlaw Roy O’Bannon (Wilson), who kinda-sorta trains Chon on the ways of the American west.

Shanghai Noon is surprisingly poky for a buddy comedy — though they meet early on, it takes a solid thirty-five minutes to get Chon and Roy working together consistently, and the movie itself runs close to two hours (a reel of extended/deleted footage on the Blu-ray would have had it running even longer). An early train-top chase is uninspired, and while the prospect of seeing Chan’s prop-filled slapstick fights in an Old West background is tantalizing and sometimes fulfilled (there’s a particularly fun bit with Chon fighting off a group of Native Americans before they become friends), the fight sequences just as often feel truncated — better than their equivalents in Chan’s other American adventures, but less dazzling than they might have been.

Shanghai Knights

Maybe Chan had greater control as the films went on: Shanghai Knights, in which the pair reunites for a trip to England to pursue the murderer of Chon’s father, moves more quickly, with plenty of hacky instigations for action sequences that you forgive because those sequences (like a Keystone Kops-style showdown in old New York, or a bit with English umbrellas that goes out of its way to break into a semi-inexplicable homage to the very American musical Singin’ in the Rain) are so much damn fun.

Despite this welcome increase in silliness, the commentary track for Shanghai Knights features director David Dobkin, who would go on to direct Wilson again in Wedding Crashers, talking with great reverence about the screenplay by series writers Alfred Gough and Miles Millar (they have their own, separate commentary) and the strong emotional core it develops via the character of Chon’s father, who is introduced and killed off within the first five minutes of the movie. Shanghai Knights is a lot of fun, but a resonant and emotionally rich adventure, it’s not. Dobkin sounds self-serious at times, but his tone also indicates surprising dedication: he’s really just made an eighties-ish sequel where heroes are reunited and placed in a new location, but he respects and honors the movie’s clear sense of fun.

It’s that sense of fun that makes the Wilson-Chan pairing inspired — the series brings out their expertise in the buddy-comedy genre, rather than wearing it thin. Both Shanghai movies, particularly Knights, have plenty of anachronisms, from soundtrack choices (Kid Rock’s unfortunate “Cowboy” in Shanghai Noon; classic-rock Brits in Shanghai Knights) to jokes about real and imagined historical figures to Wilson’s modern-sounding colloquial dialogue. Yet Wilson is quite charming precisely because he doesn’t appear to be winking at the material. His deadpan scheming and wisecracking deflates the genre seriousness of westerns and action-adventures but Roy’s neurotic concerns about his outlaw image become, through Wilson’s drawling delivery, weirdly sincere. He and Chan lend the movie a spirited sweetness not often associated with action-comedies of the early aughts.

The Shanghai pictures were not as financially successful as the Rush Hours but they did well enough; I’m disappointed that Shanghai Dawn, a pitch from Gough and Millar that they mention on their commentary, never materialized. Maybe Wilson and Chan can reunite someday as bickering, affectionate, slightly less spry old men at the dawn of the 20th century.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)