“I’m not no slave, I’m Muhammad Ali.” The phrasing is as powerful as the idea, the invention of self. Muhammad Ali was famously brilliant at such self-invention, positioning and imagining in contexts, understanding history, and especially, at making accessible and vibrant the trials he faced in the process.

Several of the most vibrant of these these form the focus of the documentary, The Trials of Muhammad Ali. As its title suggests, Bill Siegel’s movie looks at a series of legal and public challenges for Ali, beginning with the questions that swirled around Cassius Clay’s decision, following the Sonny Liston fight in 1964, to join the Nation of Islam and change his name. The film is comprised of archival footage and interviews with people who knew him when, including his second wife Khalilah Ali, whom he met when she was just 10 years old and rejected his offer of an autograph because, she recalls, he seemed too arrogant; his daughter Hannah, who calls him “the eighth wonder of the world”; and Gordon Davidson, of the Louisville Contract Group who managed him as Cassius Clay. As he remembers Cassius Clay, “He had little regard for money except he wanted it to spend.” And so he and the group “paid for everything, so he could just concentrate on his boxing.”

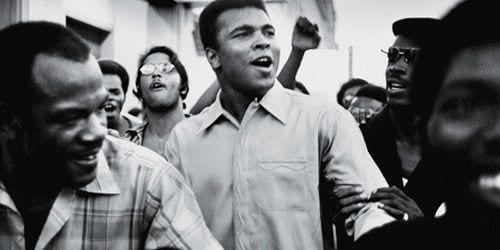

His boxing, of course, quickly led Clay to national prominence, and in 1964, he changed the nature of his celebrity when he made public his affiliation with the Nation. The film here includes an interview with Louis Farrakhan, who makes the sorts of assessments you might expect, for instance, that Ali “wanted to become a part of a movement that would free the minds and hearts of our people, so he became a follower.” This role was immediately complicated for Ali, who was never only a follower, but also a public face of most every cause he embraced or that embraced him. Just so, the film offers a remarkable collection of images of Ali, as vigorous and charismatic as everyone else describes him.

Because Ali is represented at this distance (that is, not interviewed now), he appears much as Robert Lipsyte describes him near film’s end, a product of a collective desire and also a series of changing contexts. “We created a symbol, and Muhammad Ali has long since been supplanted by what we believe he is,” Lipsyte says, “There are so many ways of looking at him that have only to do with us and have nothing to do with him.”

The film illustrates the process beautifully, revealing its appeal and effects and also its complications. It makes the case that even as Ali was coming into his own as a professional athlete and remarkably nimble celebrity, so too was he contending with his political and cultural environments. Newspaper headlines and bits of press conferences indicate the endlessly performative Ali, the ways he made sense of turmoil and celebrity. The film also raises questions about how such a public life works over time and also whom it benefits. As Ali’s immediate influence over his image recedes, his meaning is increasingly malleable.

This is one reason that The Trials of Muhammad Ali is so helpful, in that it lays out specific contexts for this shifting meaning. The contexts for his trials are vivid here, from the opening images, a segment from the television interview where David Susskind famously decried the champion as “a disgrace to his race to his country and to what he laughingly describes as his profession,” to speeches by Malcolm X (“Don’t let the white man speak for you and don’t let the white man fight for you”) and Martin Luther King, Jr., who appears in several shots with Ali, and then, as he orates, “Those who are seeking to equate dissent with disloyalty, those who are seeking to make it appear that anyone who opposes the war in Vietnam is a fool or a traitor or an enemy of our soldiers is a person that has taken a stand against the best in our tradition.”

As the film makes the case that Ali represents the “best of our tradition,” it showcases the legal trials that began with Ali’s 1967 refusal to be inducted into the US Army on the basis of his religious beliefs. Sentenced to five years in prison, he lost his Heavyweight Championship and found himself subjected to all sorts of invective, judgment, and diatribe, demonstrated so by David Susskind at the start of this documentary. Ali appealed the case all the way to the US Supreme Court, which ruled against eth conviction for draft evasion, in 1971. Observes Thomas Krattenmaker, then a clerk for Justice John Harlan, “The Ali case exposed how awkward the legal system was and how arbitrary and capricious it was.”

It also allowed Ali vindication and a return to boxing, and he went on to make more history in the ring and out of it. The Trials of Muhammad Ali frames this next set of acts in the champ’s long career as a consequence of the political courage, personal conflicts, and passionate, increasingly nuanced pronouncements he made during this period. Ali now stands as a model for political protest and social justice, and the film shows how this status was born of these trials.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)