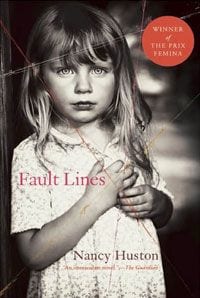

Nancy Huston, a Canadian writer living in France, has gone woefully unrecognized in the United States. Winner of the Prix Femina, nominated for the Orange Prize, translations of her work have been achingly slow to arrive Stateside. We finally have Fault Lines, a 2006 international bestseller American publishers long quailed at publishing.

Huston is a risk taker; her prior American release, Sweet Agony, depicting a gathering of friends at a Thanksgiving meal, is narrated by God. The Mark of the Angel describes an illicit affair between a German woman and a Jew shortly after World War II. The Story of Omaya, based on an actual event, enters the mind of a disturbed rape victim who must prove her assault to judge and jury. In Fault Lines, Huston makes two unusual narrative choices, working the plot backward, from present to past, and using four related six-year-olds as primary narrators. All the children have birthmarks, talismanic to some, detrimental to others.

While the backward narrative, itself a trick of plot folding, works amazingly well, the young narrators do not. Though all four protagonists are compelling, not one could be taken for a six-year-old. The language, the observations, the inner dialogue are all too sophisticated for children only a few years from toddlerhood. Nonetheless, it is testament to Huston’s talent that we are able to overlook this major hurdle, engaging with the her compelling story.

The book begins in 2004 with Sol, whose grandiose visions, sexual perversity, and violent fantasies were sufficient to scare off American publishers for two years. Kudos to Black Cat books for taking the risk of offending delicate sensibilities, for Sol is indeed a warped, alarming child, a genius who, in his words is:

“capable at six of seeing … illuminating … understanding everything”

Sol’s self assurance is abetted by his mother, Tessie, who caters to his every whim, allowing him to exist on the meager foods he likes because “they circulate with ease,” thus allowing him to “keep my mind sharp”. Controlling food is critical to Sol. He is nearly anorexic, eating only yogurt, cheese, pasta, peanut butter, bread, and cereal. He is free to come and go while the family is at table, where, after grace, his parents have fallen into the habit of applauding him, fealty he takes as his due.

Sol’s sexual preoccupations are warped well beyond his years, making them difficult to accept. He sneaks onto his parents’ computer, logging into Google, scrutinizing sites depicting rape, bestiality, and Iraqi war imagery that would nauseate all but the sickest adults. He idolizes George Bush, Arnold Schawrzenegger, and God. He longs for his father, Randall, to enlist so he can fight in Iraq.

Randall works in Silicon Valley, doing high-end defense work. A conflicted man, he has forsworn Judaism for Protestantism, church, and the religious, rather dim Tessie. His relationship to mother Sadie is rocky, but he remains close to great-grandmother Erra, a famous singer.

Both Erra and Sadie visit Sol’s household, bringing Tessie different sorts of stress. Erra’s partner of many years, Mercedes, is banned from the house lest their homosexuality disturbs Sol. Sadie arrives after a botched attempt to remove Sol’s birthmark leaves him ill and permanently scarred. A convert to Orthodox Judaism, she brings Sol a kippa, or yarmulke, a gift that horrifies Tessie.

When business takes Randall to Germany, Sadie insists the entire family go, including Erra, setting the plot into backward motion. Erra, who spent her early girlhood in Germany, has not returned since childhood. She agrees warily. Sadie organizes the trip, a bewildering event for Sol, who is airsick and refuses the groaning platter of German treats offered by Erra’s sister Greta. Further, his Great Grandmother Erra and great Aunt Greta do not seem happy to see each other. Sol spies them fighting — two old ladies — over a doll. The genius is mystified, and the story moved backward, to Randall’s point of view.

Randall’s father, Aron, is a playwright, employment that leaves him ample time to care for his son while Sadie earns her doctorate. Randall adores his easygoing father, a Jew who blithely cooks bacon and takes his son to the public pool, oblivious to his pot belly. His benign personality contrasts starkly with Sadie’s strident intensity. Her field is Lebensborn, or fountains of life — Nazi institutions where women impregnated by German Soldiers gave birth to perfect Aryan children, who were adopted out to German families. During the war Germans also kidnapped Aryan-looking children, sending them to German homes to “replace” children who had died in warfare. After the war ended, some of these children were able to return home; others were not.

Sadie is passionate to the point of obsession on Lebensborn, dragging Aron and Randall from New York City to Haifa, Israel, where she can better study. Randall is initially appalled, but comes to adore Israel, even as Aron grows increasingly depressed over the war with Lebanon. When Randall meets an older Palestinian girl at school, he falls passionately in love with her — again, a spot where having such a young narrator fails, for Randall’s love of Nouhza is that of an adult’s, even as she fills his ears with alarming information about Palestinians and the Jewish presence in Israel. But as war closes in, disaster strikes closer to home, forcing the family to leave Israel and moving the story to Sadie.

Young Sadie is intelligent, overweight, and clumsy, a miserably unhappy child forced to live with her strict Canadian grandparents while her young mother, Kristina, pursues a bohemian musical lifestyle. Repressed, filled with self-loathing, Sadie carries with her a Fiend, a hectoring voice that metes out terrible punishment in the form of head-banging. But her fortunes change when Kristina meets Peter Silbermann, whose deft management ignites her singing career. Peter and Kristina decide to move to New York, taking Sadie with them.

Sadie is entranced by her elusive, beautiful mother, now calling herself Erra, whose wordless singing carries enormous power. Peter, who is Jewish, takes his stepdaughter out to delicatessens, introducing the child to the joys of corned beef on rye while unwittingly stoking the fires of her future passion. Sadie is happy, happier than she’s ever been, until one day a man calling himself Lute appears at the door. He asks for Erra, who emerges from the bath, amazed, and begins conversing with this stranger in German, shocking her daughter. Worse, Erra leaves Peter for this man, who does nothing but sit staring, drinking too much, until the day he commits suicide in Erra’s kitchen.

The story moves to the final narrator, Erra, who in 1944 is called Kristina. Little Kristina lives with her grandparents, mother, and sister in a hamlet outside Dresden. Her father and brother are enlisted, and though she misses them, life at home is pleasant. Grandpa plays piano and teaches Kristina harmony; at night the family eats what food there is and crowds about the woodstove, telling stories. But as the war wears on, there is less and less to eat. Lothar is killed at the front; there is no word from Papa. The disconsolate family chirks up at the arrival of “Johann,” a 10-year-old orphan Mama has decided to “adopt”.

Johann is a hostile, mute child, unresponsive to his new family’s efforts at inclusion. Kristina is determined to get a response from him, and her success shatters her young life. She is not who she thought she was; there is a reason she looks nothing like Greta. As Johann draws her from her once beloved family into a crueler reality, the war comes to a close, bringing with it displacements and upheavals that will effect the entire family — right down to the Nazi-Like Sol.

Huston’s writing throughout this emotional novel is as elegant as it is wide-ranging. She moves easily from Silicon Valley to New York City, back to her native Canada, through Europe. Along the way she manages to work in political commentary on everyone from Bush to Schwarzenegger to Hitler. She sneaks in asides about Randall’s men’s group and Tessie’s many courses in meditation. Sadie’s struggles with dressing — the hell of buttons and zippers that confound all children — are amusingly depicted, as is Sol’s notion of Heaven being one large Texas, including a God tooling around in cowboy boots. Erra’s childish recounting of body parts that grow and those that don’t, including a count of her own lost baby teeth, is a rare moment where the narrator truly is only six.

Despite the problematic narrators, Fault Lines won France’s Prix Femina, deservedly so for its difficult themes and complex structure. Like Huston’s other novels, it is well worth reading, and we can only hope American publishers make her writing more readily available.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)