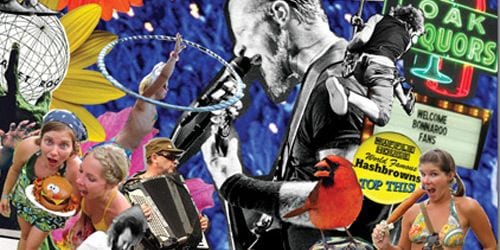

Live From Bonnaroo 2008 was originally conceived as a DVD souvenir for attendees who bought tickets to the music and arts festival last year. Directed by Sam Erickson and 44 Pictures, the product is now also available to the general public. The program on this DVD — mostly comprised of live performance footage — allows concert- goers a close-up view of the acts they enjoyed and serves as a brief festival overview for those who did not attend.

Compilers have chosen a diverse set of performers, some of whom (Les Claypool, My Morning Jacket) hew closer to the stereotypical Bonnaroo environment than others (Lee Boys, Mastodon). Headlining acts like Pearl Jam and Metallica have large followings that ensure the spectacle of a sea of bodies united in front of a main stage. But the real value of this DVD is the insight it offers on how all of the musicians gain, maintain and entertain fans through live performances at one of America’s most popular music festivals.

There is no denying the festival’s association with hippiedom. Originated in 2002 with a lineup inordinately heavy on jam bands and virtuosos, the annual four-day event in Manchester, Tennessee has become more musically inclusive over time. But the communal spirit seems almost sacrosanct to its attendees and artists, some of whom invoke the term “commune” in the footage on this disc.

That’s all well and good. But the flip side of the 80,000-strong gathering is that everyone is essentially competing for space, supplies and most importantly, position at the festival’s stages, which host an essentially continuous series of high profile acts. This sense of over-stimulation is what Gogol Bordello’s Eugene Hütz calls an “endurance test”.

One drawback of the disc’s content is that many of these defining elements of the Bonnaroo experience are edited out in favor of preserving the image of the easygoing commune. While one would not expect the penetrating camera of Gimme Shelter or Woodstock from what is essentially a promotional tool for the festival, the perspective is a bit too managed and sanitized.

Performer interviews, still photographs and verite footage of the grounds and crowd serve as interstitials between the song selections. These moments represent the biggest missed opportunity of the program, because they could provide a more in-depth examination of the festival’s culture but are disappointingly used only as transitions.

Highlights include footage from the Centeroo’s Silent Disco and an interview with local Waffle House employees about the world-famous artists who become their customers for four days in the summer. These are among the promising stories hinted at but ultimately interrupted in favor of getting to the next song.

So the performances are clearly the main concern here, and their visual and aural components are first rate. Multiple camera operators ensure that even the largest ensembles are faithfully covered and the stereo and 5.1 surround mixes created from the soundboard recordings likewise represent everyone on stage. The mixes also allow the crowd noise to occasionally appear, which preserves the performer/audience interaction so crucial to a music festival of this sort.

In fact, it is this relationship that also repeatedly comes to the fore throughout the program as a kind of evaluative standard for the performances: Which acts get the crowd going and which do not? To determine this is to go beyond trying to separate the good performances from the bad. Again, as this is a promotional program, there are really no total stinkers to be found. Instead, it is interesting to observe the interaction between performers and spectators and especially fascinating when that interaction defies expectations.

Legend (or at least the Web echo chamber) has it that rock audiences became fully comfortable moving to music again sometime around 2002, thanks to The Rapture’s “House of Jealous Lovers”. A continuing stream of DFA hits, Gregg Gillis, Dan Deacon, and a late-to-the-game reversal of opinion on Daft Punk have kept “indie rock” crowds dancing throughout the decade. But the instinctive need to sway, bob and bounce to music has neither a birth nor expiration date, and it exists and extends far beyond the critically sanctioned electronic music crossovers of late. This impulse is essential to the communal festival sway with which Bonnaroo artists hope to connect.

To that end, few tracks on this program have more potential to make the crowd get down than “Let Them Knock”, rollickingly performed by Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings. Yet even as Jones attempts to engage the spectators, audience members remain largely indifferent. The cameras capture a few wide shots where some people seem to get into the tune, but the effort Jones and her band put into the song significantly trumps the energy of the reaction. One pale, sunglasses-wearing couple at the front of the audience remains comically stoical, as if willfully defying the urge to move.

Conversely, the camera finds a much more active audience as Broken Social Scene plays Brendan Canning’s “Love is New”, a annoyingly repetitive clunker a world apart from the band’s more energetic material like “KC Accidental”. The disparity of reactions to these two performances suggests that sometimes inhibition decreases only as the hip factor of the artist increases.

Among the pleasant surprises here are the Avett Brothers, who use forceful folk rock to whip the crowd into what looks like a rare unselfconscious frenzy. And Miami’s amazing sacred steel ensemble the Lee Boys use “Come On, Help Me Lift Him Up” to inspire raised hands and elevated spirits amongst a crowd who might not know what has just hit them but does not let that get in the way of shared excitement. Additionally, when compared to Roosevelt Collier’s inspired pedal steel work on this number, Kirk Hammett’s solo on Metallica’s “Fade to Black” seems routine.

In one of the brief artist interviews, Against Me! drummer Warren Oakes says that the difference between playing a club show and playing at Bonnaroo is that he does not expect the latter crowd to know his band’s songs and sing along to the lyrics. He regards the festival as a chance to play to a group of listeners mostly unfamiliar with Against Me!’s music.

The band’s go-for-broke rendition of “We Laugh at Danger (And Break All the Rules)” is a crowd pleaser that illustrates the kind of audience conversion Oakes describes. Ironically, it takes a punk rocker to elucidate the rather hippie philosophy at the core of the festival: An artistic and commercial symbiosis, wherein bands and fans sustain each other.

There are no bonus features, though additional content offered through the Bonnaroo website contributes to a more detailed picture of the experience for audience members who want a comprehensive look beyond this 16-artist showcase.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)