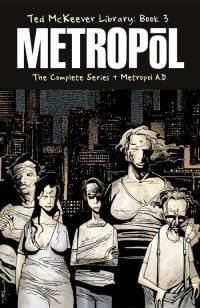

Cities are often represented as alienating places, where in a sea of people, a good portion of its population finds itself in a crowded loneliness. Take those sad disconnects, add in a dose of Gnostic end times, and you start to get an idea of where Ted McKeever was going in his early 1990’s series Metropol.

Drawing on the apocalyptic stories of the non-canonized, Biblically ambiguous Book of Enoch and the strangely accepted Revelations, McKeever examined how individuals become moral creatures in an immoral society, and how their positions change when an event drastically shifts the traditional social order. He situated this subject within a long literary tradition examining this theme, ending the original issues with quotes from philosophers, novelists, and mystics. Few books from a Marvel subsidiary in the 1990s can attest to quoting Camus, William Blake, and Churchill on their back covers, which is, in a way, telling of the grandiose nature of McKeever’s project.

By opening the work, we are thrown into the dream world of Jasper Notochord, where imagery and self-examination set out the central ideas that the rest of the series attempts to address: what makes a person good or evil, and how do categories muddle our judgment on ethical matters? When Jasper awakes from his dream, he is thrown back into the monotony of getting ready for work before being disrupted by the vague accusations of inspectors at his doorstep. As in Kafka’s Trial, the inspectors order the accused around and play upon his guilt before authority to maintain their power in this passing interaction. In the midst of it all, Jasper’s body is slowly being taken over by the angel Enoch, and, as in the Book of Enoch, he begins to dream of how the history of the world will unfold.

As the apocalypse begins and other people begin to transmogrify into demons and angels, the traditional order of law is, of course, ultimately displaced by a higher order. Angels and demons are fighting a war for the city, and the new world ends up being based more on us vs. them and defense of the pack than a rational ethic. All of this is confused by the categories of judgment that no longer hold up in the new order of things. As Jasper asks the angel that shares his dream space, and eventually his thoughts, “What significance are these images? Should I be reading something into them? Or do I accept them for what they are…”

Differences in past vocation mean little in the new order. A serial killer, a video store clerk, and a couple of sex workers undergo varying transformations as the city becomes the center of a cosmic battle, and modern ideas about the self and good and evil are displaced by medieval variants. It doesn’t look anything like Augustine’s City of God; its walls are guarded by a giant slug, and, in the end little hope remains for the angels of heaven.

The overall work suggests a kind of individual relativism within the frame of uncontrollable historical events. The way we judge our own actions and others in the context of these events is based upon who we have become over our lifetimes, though, in a moment, the kingdoms of heaven and hell can meet in our city, creating an event that redefines who we thought we had become. Stripped from legalistic morality, the characters become tribal defenders running around with nuclear weapons, apropos of the actual Cold War the book almost gives closure to. Aside from mutual animosity and one angel’s early offering of armistice, the only difference between the demons and the angels is their conflicting desires to destroy and protect humans, respectively.

As a physical object, the heaviness of this reprint of the Metropol series as the hardcover volume three edition of McKeever’s anthologized works is pleasant to hold. Unlike the original series, however, the book is in black and white, without the strange colors that gave Metropol its dark tone. The original inking was done for color, and the reprint lacks the contrasted shading required for a black and white work. Further, in the first issues of the original, some caption boxes were different colors to help the readers recognize whose voice they were reading in conversations between two consciousnesses occupying one body, which is confused or lost in this edition. A few of the original issues also contained extra stories at their ends setting up the return of Eddy Current, written by McKeever and illustrated by Mike Mignola. These stories did not make it into this volume and cause for a strange jump of the character into the main narrative. It also would have been nice if the quotes that framed each issue in the original series were somehow included in this reprint, even if only as end notes. Though these sacrifices were undoubtedly to make the book more affordable, these losses should be noted.

Despite the minor flaws of this edition, the body of work that makes up Metropol stands the test of time. And though it doesn’t clarify the lines that we draw to divide good and evil, no book of this scope should. In the process of this exploration, it does inspire thought and a laugh, which is more than can be said of the majority of books on apocalypse these days.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)