Beyond the Valley of the Dolls works most clearly as a deconstruction of Hollywood’s own conservatively finger-wagging yet exploitive morality tales, in that neither the finger-wagging nor the exploitation can be taken seriously. From there, it gets weirder in at least six ways.

1. The whole movie.

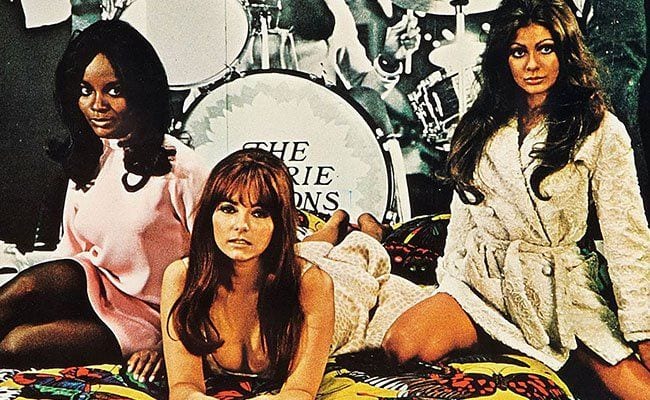

This gaudy, Day-Glo, music-filled fable spells out the fatal lure of Hollywood sex and drugs for an all-girl rock group called The Carrie Nations, a trio of wide-eyed youngsters resembling Josie and the Pussycats. The height of spoofy self-consciousness occurs at the climax, when a trussed and bug-eyed blond stud, clad only in a loincloth, tells a stoned, red-caped, faux-Shakespeare-spouting, Prince Valiant-haired Svengali that it’s all been a put-on from the beginning, man, only he’s been taking it seriously.

Then the 20th Century Fox fanfare music bursts into the soundtrack as someone starts running riot and turning the comic soap opera into a crazed Manson-family gorefest. By this time in an over-the-top movie, it seems par for the course. Oh yes, that’s also the scene containing a shocking, indeed flabbergasting, indeed nonsensical revelation about one of the characters–one that screenwriter Roger Ebert said he basically made up out of the blue when he got to the end of the script. Which brings us to:

2. The script is by famous film critic Roger Ebert.

He’d made friends with filmmaker Russ Meyer after saying nice things about some of the man’s cult hits, so Meyer invited him to Hollywood to write a script in six weeks. The project was intended as a sequel to the critically derided, vulgar, slick popular hit Valley of the Dolls (1967), based on Jacqueline Susann’s critically derided etc. bestselling novel.

In his commentary and other extras on the new Blu-ray, Ebert says he and Meyer found that movie ridiculous and self-serious and decided to lampoon it by recounting basically the same story in an even more clichéd and ridiculous manner. This makes more sense, if that word can be applied to this movie, than seeing it as a comment on flower power or youth culture or Hollywood immorality or anything like that. It works most clearly as a deconstruction of Hollywood’s own conservatively finger-wagging yet exploitive morality tales, in that neither the finger-wagging nor the exploitation can be taken seriously.

The story’s milieu is a special mythical corner of The Establishment: the Los Angeles entertainment world of celebrities, hustlers and wanna-be’s. The characters work in the fashion industry, music industry, movie industry, professional boxing, and the legal profession, and they makes lots of money and spend it on the materialism of mod clothes, cars, drugs, houses and pools. There’s not a hippie in sight, although one clueless old fuddy-duddy, with fantasies of free love in his head, keeps calling the lead singer a hippie until she tells him he wouldn’t know a hippie if he saw one.

It’s one of the few valid comments in a movie where virtually every line of dialogue is off-kilter in a faux-hip way, most famously the exclamatory gibberish of “This is my happening and it freaks me out!” (The reply: “It’s a stone gas, man!”) Susann sued 20th Century Fox over this disrespectful, nonsensical non-sequel, claiming it hurt her reputation and winning posthumous damages; there’s a bonus weird fact within the weird fact.

Here’s another: Ebert and Meyer collaborated again on a script for — wait for it — The Sex Pistols. The band loved Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, which played regularly for years in a London theatre, and contacted Meyer to star them in a film. Due to monetary reasons related to the group’s self-destruction on its American tour, the plug was pulled after a few days of filming.

In his comments, Ebert states that he didn’t “compartmentalize” or disown his work or friendship with Meyer, even though it might be regarded as disreputable. He emphasizes its plaudits, such as Richard Corliss declaring Valley of the Dolls one of the ten best films of the ’70s, or feminist critic B. Ruby Rich’s defense of Meyer as a “feminist filmmaker” because his films center on powerful women who dominate the plot at the expense of weak men.

By a psychologically rich synecdoche, Meyer’s frank admiration for large breasts led his work toward a concomitant idealization of strong, highly sexualized and even violent women, as with the titanic she-demons of Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) and the “moralistic” hit Vixen in 1968, whose success triggered his short-lived contract with 20th Century Fox.

3. It’s edited like the movie’s blinking for you.

Meyer, trained as a WWII combat photographer and then a maker of industrial films before pivoting into the world of Playboy centerfolds, netted a ton of money with independent “nudie films” that made him famous — or at least notorious. They were marked by his highly professional pictorialism of composition, the aforementioned fetish for large breasts, and an attention-deficit style of editing that was previously seen only in avant-garde items and certain silent films of Sergei Eisenstein and Abel Gance.

Only Richard Lester was as consistently hyper with editing in the development of a style associated with rock music and all things mod, such as TV’s Laugh-In. More than 20 years later, it became known as “MTV editing” and modern action cutting.

According to different theories, Meyer evolved his unique variant in order to cover the shortcomings of non-professional actors, or because he had a phobia of seeing actors blink. No scene or dialogue can be presented in one or two set-ups when 12 is possible, flickering back and forth such that cuts are somehow inserted between the “normal” cuts. It’s nonstop, and it makes the movie a dizzying, disorienting, artificially hallucinogenic experience even today, which is why nobody could make head or tail of the pan-and-scan release back in the era of VHS tapes. It must be seen in full widescreen, and preferably replayed in order to fully process the happening without freaking out.

4. The music is really, really good.

Stu Phillips, primarily a TV composer, provides a score that contains the movie’s only explicit winks to the audience. Various spoofy or parodic cues call attention to themselves, like snippets of Wagner and Dukas and the syrupy music in the hospital scene, which comes straight out of TV shows like Dr. Kildare and Medical Center. In fact, much of this film nods to contemporary TV hipness and camp, from Laugh-In to the climactic use of Catwoman and Robin costumes from Batman.

None of that nudging and winking applies to the string of knockout songs for The Carrie Nations. They’re not spoofs, but genuine power-pop driven by the incredible voice of Lynn Casey, who dubs for Dolly Read. In one of the extras, Casey discusses the fact that she was dating a man who got killed in the Manson murders, and he’d invited her out that night. She ended up singing in a movie whose ending was inspired, in a totally off-the-cuff and in-the-moment manner, by those headline events. That’s zeitgeist crossed with Twilight Zone.

5. Unknown then, unknown now.

Meyer cast the film with novices who have remained, for the most part, unknown despite the movie’s popularity. Of the main trio, Dolly Read and Cynthia Myers were Playboy models while Marcia McBroom was an African-American fashion model. Of the men in their lives, only Harrison Page has had a lengthy career, mainly on TV. Michael Blodgett soon quit acting to become a writer. John LaZar has shown up in “cult” trash, and David Gurian never acted again. They’re known for this big hit and that’s it.

Erica Gavin, who plays a lipstick lesbian (quite distinctively), is known for this and Meyer’s Vixen. Edy Williams, as an unapologetic female lothario (lotharia?) who screws men and dumps them, was married to Meyer during the ’70s. In the minor role of Aunt Susan is Phyllis Davis, later a regular on TV’s Vegas. In an even more minor role, square-jawed Charles Napier is the only person whose consistent career as a character actor would make him familiar to the average film-watcher.

6. It’s on Criterion!

According to Ebert, 20th Century Fox spent more than 20 years trying to disown and erase this film from its official studio histories despite the money it made. They were proud of other ’70s hits like MASH, Patton and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, but overlooked this film and the similarly jaw-dropping and polymorphously transgressive and tasteless Myra Breckinridge, seemingly embarrassed by them.

The studio execs wanted an R rating for Meyer’s film and were annoyed when it got slapped with an X; it’s been re-rated at a still absurd NC-17, while Sasha Baron Cohen comedies are more offensively explicit. Meyer was annoyed by the X rating too, only because he’d have shot much more nudity if he’d known, but the studio wouldn’t allow reshoots to make it more extreme.

Now this bizarre slapstick satirical musical melodrama, condemned by most righteous tastemakers while audiences lined up in 1970, has received the deluxe Blu-ray treatment from Criterion — just like something from Bergman or Fellini. The HD digital restoration is, honestly, dazzling. The optional subtitles are a must to follow the crazy, sometimes obscurely tossed-off dialogue, which can be hard to catch amid the flurry of breakneck edits. Who, when processing a sudden flash of nipple peeking above a neckline, notices the random line “Plastics, Benjamin”, functioning as a reference to The Graduate and a visual pun?

From Fox’s 2006 DVD, they’ve retained Ebert’s commentary (recorded in 2003 for a previous Criterion edition that never materialized) and the scatterbrained multi-actor commentary as well as the making-of material, screen tests and trailers. The still galleries and LaZar’s intros haven’t been included. There’s a British TV interview with Meyer from 1988, a festival Q&A of poor tape quality dating from 1992, and a new rambling appreciation by (who else?) John Waters.

In 1970, this piece of cinema brilliantly turned a legally required disclaimer into a come-on with the tag: “This is not a sequel. There has never been anything like it.” Today, those involved seem half-proud, half-bemused by a flummoxing specimen that leaves audiences uncertain of their response. Strung from straight-faced, straitlaced clichés while making fun of them in an ambiguous tone that must often be decided consciously by the viewer, or ignored at our peril, it challenges the expectations that are supposed to cue our responses.

In the final words of his commentary, Ebert says it’s improper for him to review something he made, but he will say that unlike many movies, it doesn’t bore him. It’s also not something one forgets, and possibly these qualities are enough for any movie.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)