“The invention of the camera,” argues art critic and writer, John Berger, in his seminal text, Ways of Seeing, “changed the way men [sic] saw.” Through this technological innovation, images which were once categorised in the exclusive domain of ‘art’ became widely and simply disseminated. The result, a profound shift in the meanings and values conferred by such images and their genre.

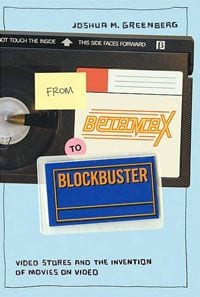

Arguably, the VCR has performed a similar function. Images, albeit moving, which were once confined to one time viewing opportunities when broadcast or on the cinema screen, can now be stored, viewed, and reviewed at leisure. However, while Berger’s interest lies with the image itself, Joshua M Greenberg’s text From Betamax to Blockbuster, is instead concerned with the tool by which images are replayed.

Thus, the spools of magnetic tape encased in plastic, and the black box which sits beneath the TV, are shown to be more than simple vectors of cultural distribution and instead are entities worthy of analysis in their own right. The VCR, as Greenberg shows, was invented and promoted by manufacturers with an avowed purpose in mind. In everyday use, though, the technology became reinscribed, leading to a sociocultural shift the outcomes of which remain with us today.

Greenberg’s approach is one tracking a technological history. Such a slant allows him to follow the (accurate) assumption that the days of the videocassette as a viable storage medium are over. Analytically, therefore, he benefits, evading the need to frame his arguments with the disclaimer that future developments might throw a spanner into his theoretical works. Greenberg’s thesis follows a well trodden post-structuralist path. He is, he states, less interested in the materiality of video technology, than in the knowledge systems which surround it.

Video cassettes and VCRs have no inherent meaning or purpose, rather, significant actors related to those systems generate their own meanings over time, which come to shape the development of that technology. Further, by pulling his focus towards the VCR as a technological phenomenon, rather than a cultural one, Greenberg demonstrates his misgivings on the bifurcation of medium and message. The two should be conflated, he suggests, for to comprehensively understand the intricacies of one requires an awareness of the influence of the other.

And so the story opens. In the mid-’70s, electronics giant Sony released the Betamax video cassette recorder to the American market. This device, they suggest, will be used to shift time, revolutionising television watching as viewers are released from the shackles of broadcast schedules and instead able to record output for later playback. Due partly to technical constraints (original Betamax tapes could only hold an hour of content), and partly to short-sightedness, Sony failed to see beyond time shifting. There was no engagement with some of the world’s largest content producers — the movie production companies — and as a result “for the first two years that the Betamax was available, the only prerecorded tapes which users could legally buy were either in the public domain or pornographic”.

In spite of this, the technology’s users soon realised the potential video recording held. Early owners, seeking personal copies of movies or series not broadcast in their area, would travel, VCR in tow, to a place in which the show could be received. Soon, however, peer-to-peer sharing networks sprung up. In fanzine-esque publications such as The Videophile’s Newsletter, arguably the low tech precursors to today’s online music and video distribution, VCR users would list their collections of TV shows and movies archived from their own recordings, which they would then trade, on a tape-for-tape basis, with other users.

It was these peer-to-peer networks which precipitated the transformation of the video recorder from the time-shifting device it was originally promoted as, to a machine for viewing prerecorded video cassettes. Rather than the manufacturer having dictated the correct use to which their product be put, amalgams of users linked in loose social networks had revolutionised the meaning invested in the technological artefact known as the VCR. Unbeknownst to them, this activity would initiate a sea change in the consumer landscape which would be highly influential in the triumph of VHS over Betamax, and would eventually generate a whole industry, and indeed lifestyle choice, centered around a night in with a movie.

Greenberg’s later chapters explore this in spectacular depth. From the humble VCR radiates discussions and analyses on an array of interweaving topics. He traces the development of video rental stores as they move from the early, family owned, artisanal establishments to the international chains seen most commonly today. He discusses the retailers who sold the VCR units, and examines the status of the VCR for home users.

The real fascination in this writing comes from the depth in which he explores these phenomena. From meticulous research — Greenberg would have not have been long out of diapers at the time much of what he discusses was taking place — everything from the social and professional linkages between video rental store owners, to the experiences of those store’s users is documented. The provision of such rich supporting material is a result of The Videostore Project, Greenberg’s innovative web based research tool. Like an oral history, respondents, garnered from advertisements in trade magazines and through personal contacts, are encouraged to enter their personal narratives of involvement in the movie store scene.

As movie rental gained momentum, so it influenced the on screen form the movies themselves took. Practical considerations, particularly the dimensions of the television screen versus that of the cinema, required consideration in the transfer of a movie from one medium to another. The impact of such technologically led adjustments to the integrity of the movie as a cultural artefact became increasingly important as studios began to realise the centrality of the home video market to their profit margins. As such, artist and aesthetic judgements, and in particular one decision made by Woody Allen over the video release of Manhattan, have had lasting impact on the way movies are viewed in the home.

On depth, variety and originality, Greenberg’s text cannot be faulted. The narrative he traces provides a compelling, relevant, and often amusing precursor to technologies such as the DVD or harddisk enabled digital television, which are so central to the mediascape we currently inhabit. The text’s central downfall is, therefore, its rigid adherence to academic convention. As Greenberg notes in his blog, the text, the published write up of PhD research, was released as a trade publication rather than having been directed at a general audience. As such, its style and format is likely to be off-putting to a wide readership. Which is a shame, because in both narrative and content From Betamax to Blockbuster is well worth a read.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)