In the wake of the historic election of Barack Obama to the office of President of the United States, many pundits and commentators abandoned their usual discussion of the minor aspects of policies and electoral politics to appreciate the immense significance of the event. Those who did and did not support his candidacy can agree on one thing: that President-elect Obama represents a tremendous milestone in the history of a country scarred by the evil of slavery and haunted by the racial divisions sown by our forefathers. To hear from notable black Americans who participated in the civil rights movement, such as Georgia representative John Lewis, as they confess their doubts that they would ever live to see such an event transpire and celebrate with elation that they did, it compels us to look back at the names and faces of those who worked so hard to make these dreams reality.

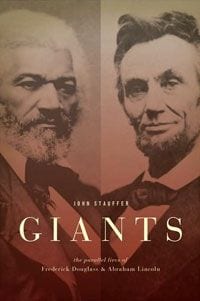

In this sense, Giants: The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln is an extraordinarily apt book for our times. Obama’s political and personal pedigree has drawn comparisons to both men. Like Lincoln, Obama is an Illinois politician who rose to the White House rather briskly in a time of immense social strife. Like Douglass, he is a powerful orator, community activist, and is of mixed race. Like both men, Obama is a self-made man, working tirelessly to educate himself, experience the world around him, and achieve heights of success that one would not expect of someone from humble beginnings.

Author John Stauffer lectures on the history of American civilization and is a professor of English at Harvard University. He is well versed in the politics and culture of the United States in the mid-19th century, having previously written books on radical abolitionists like martyred firebrand John Brown, and edited Douglass’ own writings for modern publication. Giants is meant to be a dual biography, following Lincoln and Douglass through their lives and careers in alternating chapters so that we not only have an understanding of what each man was doing, but of what they were doing in relation to one another in the same time period. Stauffer’s intention is to demonstrate how both men transformed themselves in their efforts to transform America, and that their paths, though varied by circumstance and station, were very similar.

Growing up in what was then the frontier, Lincoln was considered “white trash,” as Stauffer puts it, the son of a single father who hired his child out to work for strangers and felt trapped by his rustic, provincial surroundings. Douglass, bound at birth by slavery, had a relatively placid childhood compared to his fellow slaves, owed in part to the fact that his father was almost certainly his mother’s slavemaster, Aaron Anthony. It was not until his teen years that he endured the harsh treatment typical of the times, at the hands of the notorious Edwin Covey. Stauffer demonstrates in amusing and enlightening fashion the pivotal role fisticuffs and fighting had in helping Lincoln and Douglass define themselves and take control of their fates. They were strong men from the start, unwilling to bend or bow to external forces.

Lincoln and Douglass were low-caste figures in American society and being intelligent young men, they knew it, and struggled to escape it. Both identified reading and education as the key to their ascendance, and each took solace (and early moral and political shaping) from a book titled The Columbian Orator.

While the early childhoods of Lincoln and Douglass bore a slight resemblance to one another, the two men seem to sharply diverge when they begin their careers. Douglass is a gifted speaker and intellectual, and once he attains his personal freedom, he exercises his freedom of speech at every opportunity, his oratory swinging between caustic and mellifluous, a verbal rope-a-dope that left audiences reeling and begging for more. His chapters in Giants are incredibly entertaining, as he is endlessly outspoken, truly brilliant, and marvelously inspiring.

Lincoln, on the other hand, spends much of his early career being the consummate politician: dissembling, vague, and callow. His two years in the House of Representatives are undistinguished, even disappointing, and some of the stories of his time in Illinois state politics are downright embarrassing. He clearly feels that slavery is wrong and founded on flawed principals, but makes no significant effort to bring about its end, fearful that it will submarine his fledgling political career. Stauffer highlights Lincoln’s early support of repatriation of American slaves to Africa and his notion that while slavery might be abolished someday, it would probably not be able to be eliminated fully until the 1950s. Eventually, the Abraham Lincoln we know and love as the savior of the Union emerges, but his transformation is treated rather superficially by Stauffer, and there doesn’t seem to be a clear fulcrum for his shift from mealy-mouthed careerist to the monumental figure remembered in most history texts.

In Stauffer’s telling, Douglass is the only giant of the story, a colossal and towering figure whose advocacy and activism planted the seeds of today’s history-making election. Lincoln seems lightly treated throughout Giants, overshadowed by Douglass’s intensity, and so this dual biography feels lopsided, unbalanced. Readers may wish to delve more deeply into each man’s life one at a time, rather than together, to avoid making too many unfair comparisons and to give each the focus they deserve.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)