Mike Ripley, by the numbers, is a former crime novel columnist who has reviewed more than 950 books. He is also the author of 21 crime novels himself, and has been an avid reader of thrillers for the past 53 years.

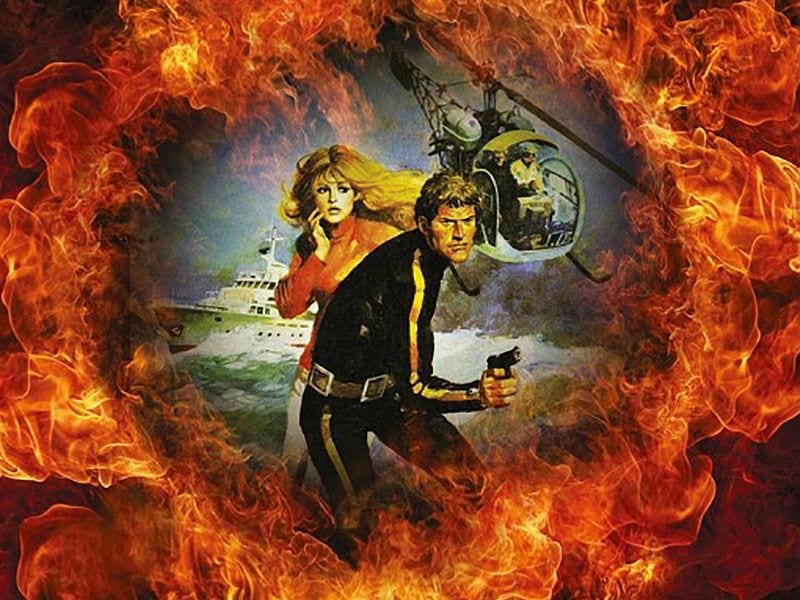

It’s that last item on his numerical resume that was the driving force behind Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed—a sexy title for what Ripley calls “a reader’s history” of “that action-packed period around the Sixties when, having lost an Empire, Britain’s thriller writers and their fictional heroes saved the world and their books sold by the million.”

Like most male Baby Boomers, Ripley recalls loving WWII literature as an adolescent, and notes, “Thriller writers quickly realized that if their plots struck a familiar resonance with the war, they would find ready acceptance among a young male readership.” When that profusion of war adventures morphed into Cold War espionage, he became a fan of those novels too.

Ripley admits that this book “concentrates unashamedly on the

British spies, secret agents, and soldiers, and their creators and publishers, who saved the world from Nazis, ex-Nazis, proto-Nazis, the secret police of any (and all) communist country, super-rich and power-mad villains, traitors, dictators, rogue generals, mad scientists, secret societies, ruthless businessmen and even, on one occasion, an ultra-violent animal protection league which kills anyone who kills animals for sport.”

Zeroing in on British postwar thrillers from 1953 to 1975 seems like a reasonable task, until you realize that Ripley (and the dictionary he cites) broadly considers the thriller to include crime, spy, and adventure fiction. He also attempts to include film references—pointing out, for example, that the “breezy energy” of the first Bond film,

Dr. No, “set a fashion for spy fantasy fiction (and film) which was to dominate the rest of the decade, encouraging several hundred authors” to “board what was thought to be a gravy train.” Even if, as Ripley maintains, much of that boom-era fiction never made it past the Sixties, what survives is still a huge body of literature (and film)—a bit much, perhaps, for one volume.

Why do I sense this? Because Ripley apparently does. Occasionally he hints at the limitations he faced (“to take, perhaps unfairly, just one example of many”) and says, in making one important argument, “It would be stretching a point to say that without Eric Ambler there would have been no James Bond… But in one way one could have said in 1957 that without Eric Ambler there would have been no

more James Bond.” Yet, Ripley doesn’t offer a satisfying explanation for why this is so and elsewhere admits, “I should insert here a warning: fans of Eric Ambler (1909-98) and Graham Greene (1904-91) will feel themselves short-changed” because, he explains, “they had cemented their reputations two decades previously.” Here too, their influence is never fully discussed, and at times readers may find themselves, as I did, wanting more explication than what Ripley provides in this ambitious survey. And it is a survey.

Ripley’s overview of spy, crime and adventure thrillers reads as breezily as some of the novels he’s describing, but because of the sheer volume of material his study necessarily skims the surface. Comprehensive as it may seem, several of the book’s 12 chapters read like lists of novels briefly summarized in the context of the chapters’ overriding themes. Shooting for a popular audience, Ripley doesn’t cite many authorities, and the endnotes don’t contain full publishing citations or even page numbers. For that matter, the bibliography in this 266-page study (plus 162 pages of appendices and indices) cites only 30 books—none of them scholarly. Instead, Ripley relies on his own extensive background, and for the most part it would have been enough, had he gone into a little more depth in key places or narrowed the topic to allow him to better do so.

Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang takes its title not from the Pauline Kael collection of film reviews, nor the Ashley Antoinette novel, nor the 2005 movie of the same name. It comes from a letter James Bond creator Ian Fleming sent to Philip Marlowe creator Raymond Chandler: “You after all write ‘novels of suspense’—if not sociological studies—whereas my books are straight pillow fantasies of the bang-bang kiss-kiss variety.” Fleming and Bond merit a chapter of their own in Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang and also feature prominently in a fascinating chapter that focuses on the great British thriller boom of 1962—a banner year only marred, ironically, by Fleming’s “ill-judged attempts to get into the female sexual psyche in The Spy Who Loved Me“, which Ripley tells us “one British magazine editor” called “one of the worst, most boring, badly constructed novels we have read.”

Some of the stronger chapters are those in which Ripley not only situates the fiction in the context of the genre, but also explores the forces behind the growth and popularity of the thriller. After two slighter chapters dealing with definitions (“What makes a good, or best selling thriller is anyone’s opinion or guess”) and a pre-Bond landscape, Ripley offers a satisfying summary of the postwar years, a “decade when Britain had to come to terms with being ordinary” because, exhausted and bankrupted by the war and an emerging domestic welfare state, it was no longer a global power.

In another engaging section Ripley discusses the military service and espionage backgrounds of the writers who would rapidly achieve popularity in the genre. “Of the 155 authors mentioned in this study for whom career details are known,” he writes, “over 70 per cent had experienced active military service other than peacetime National Service, or were professional journalists, in some cases both.” To reinforce his sense of the thriller as a largely male entertainment, he notes that only five women are included among the 155 writers he deemed major players, and Ripley tells us that two out those five also came from military, spy or journalism backgrounds.

Some of the insights are obvious—that ’30s “Golden Age” detective novels “required writers to be more than well born, well bred, and well educated” or that spy novels were powered by exotic settings, technical information military weapons and spycraft, for example—

Kiss Kiss gets the most Bang Bang when Ripley offers bits of trivia that go beyond capsulate plot summaries for the novels he mentions.

It’s fascinating to hear him credit James Fennimore Cooper for giving us early prototypes for the espionage and adventure thrillers (

The Spy, 1821; The Last of the Mohicans, 1826), or for him to detail how Alistair MacLean was the first to write postwar thrillers that went beyond the war-related plots and gave readers juicy conspiracies to chew on: “Is there a traitor among them, is the mission the real agenda, and are there enemies other than the Japanese or Germans?” As Ripley explains, “Played out against a ticking-clock scenario, MacLean invented a template for the adventure thriller.”

It’s interesting, too, to page through a chapter about the real-life events that influenced spy thrillers in the ’60s, and fans of biotech/scientific thrillers will enjoy learning about Ian Stuart’s

The Satan Bug, which Ripley credits as a forerunner of the genre, a novel that a reviewer for The Sunday Citizen praised for having “one of the most exciting plots since the first James Bond novel.”

Ripley asks, “Was it a golden age or an explosion of ‘kiss-kiss, bang-bang’ pulp fiction which reflected the social revolution—and some would say declining morals—of the period?” In the end, I’m not sure that he ever provides an answer. Maybe it doesn’t matter.

John Updike once advised book reviewers never to blame an author “for not achieving what he did not attempt”, and I must admit that as a “reader’s history”, Ripley’s book does what the author intended: it provides fans of the genre with a personal introduction to books they may not have heard of, so they can add them to their reading lists or seek them out on abebooks.com or bookfinder.com. To me, that’s this book’s greatest value—a value that would have been enhanced had Ripley not only provided appendices that list major/minor writers and some of their best-known books, but also provided a ranked list of the Top 50 or 100 thrillers from this period. As

Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang proves, there’s probably not a person more qualified to assemble a consummate reading list for thriller fans.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)