At five years old, Pinki has already endured a lifetime’s worth of trouble. Born with a cleft lip, she has stopped going to school because, her father Rajendra explains, the other children called her names and made her feel ashamed. It’s “because of the eclipse,” her father explains, the one that occurred when she was in the womb. “It was God’s will.”

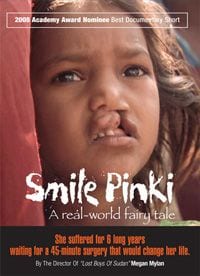

Meeting with Pankaji Kumar Singh, a representative from the GS Memorial Plastic Surgery Hospital, Rajendra doesn’t believe anything can be done about Pinki’s lip. In particular, he worries about paying for an operation. It’s “completely free,” insists their visitor. Rajendra, his wife, and their in-laws all look skeptical now. A moment later, however, they’re making plans to travel from their village, Uttar Pradesh, to the hospital in Varanasi. It’s no surprise, given that she’s the titular subject in Smile Pinki, the Oscar-winning short documentary that premieres on HBO on 3 June.

As producer/director Megan Mylan recalls, she was approached by Dr. Subodh Kumar Singh (no relation to the social worker Pankaji), with hopes of publicizing the work of the NGO Smile Train in association with GS Memorial. After some deliberation, she agreed to take on the project (“I have a background in working in international development,” she says, “So I have a pretty high bar for what I think is an appropriate model of ways that Americans can be effective”), with the understanding that her preferred “verité ” approach might be applied to a “good story” with (“very strong, individual characters.” In this case, children going through “once in a lifetime experiences” seemed apt subjects.

With Pinki at the center, the film looks in on the experiences of a few other children discovered by Pankaji, including 11-year-old Ghutaru, who has not only stayed out of school but has also largely stopped talking (as his cleft palette affects his speech). The film opens on a schoolyard scene, with children in uniforms dancing in a circle, their sense of community and hope manifest. This, the film suggests, is the life available to children with cleft deficiencies, if only they undergo corrective surgery. (From here, Rajendra adds, his daughter can look forward to a better future: “If it’s done, she’ll be able to live a decent life and get married”).

In India alone, an estimated 35,000 children are born with cleft deficiencies every year; the film notes that impoverished children are eligible for free corrective procedures, but their parents either don’t know of such options or resist them because of fear and superstition. (More than one conversation with doctors reveals that mothers tend to be blamed for the defect, with some then abandoned by unhappy husbands.) The film makes this background clear through repeated shots of the villages where Pinki and Ghutaru live: people herd goats or work in fields, their bodies bent over and wiry; they collect water from wells and ride bicycles along dirt roads. Their poverty is a fact of life, endured without complaint and rendered here without commentary; preparing for his journey, Ghutaru pulls on a pair of clean pants several sizes too large; at the hospital following the surgery, Pinki’s uncle makes what appears to be his first phone call ever. “We are all fine,” he reports, with some help as to how to hold and speak into the receiver.

While such details provide helpful background, Smile Pinki keeps focused on the kids’ experiences. When, at the hospital, a mother expresses her relief to learn that her family is not alone in dealing with a cleft deficiency, the camera looks over at Pinki, wordlessly gazing up at a slightly older girl. At another table, a doctor asks a father how his daughter’s hands have come to be so worn, only to learn that the man has her doing housework since his wife’s death — until the man remarries, the doctor understands, the daughter, no matter her youth, is responsible for domestic chores. The staff members repeatedly tell patients their lives will change, that they will especially need to go to school: “Once your lip is fixed,” one doctor instructs, “You need to either study or learn a trade at your aunt’s. You won’t play all day, right?”

The film doesn’t look into possible reasons for cleft deficiencies, which range from missing vitamins or faulty pituitary gland activities to some sort of genetic cause, mentioned here by Dr. Singh. He focuses on “decent treatment,” noting that as the Smile Train program succeeds, another problem has come up, a backlog of cases that means some children must now wait for their surgeries. Pinki and Ghutaru don’t have to wait in the film, but are instead admitted, interviewed, and apparently treated from the day they arrive at the hospital. It’s unclear whether this has to do with the camera crew that’s following them, but the experience serves to build another sort of community, one that can be expanded through word of mouth. “You have responsibility to help other patients,” a staff member tells families about to leave. “Without patients, a hospital is useless.”

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)