Princess Sikhanyiso, also known as Pashu, is the eldest of her father King Mswati III’s 22 children. A dutiful daughter and self-described “rhyme slayer,” the amateur rapper leads a film crew through the King’s palace in Mbabane, capital of Swaziland, pointing out the gigantic swordfish that adorns “one of the rooms for most important visitors.” She smiles politely, anticipating her upcoming 18th birthday and comparing the tour to MTV Cribs.

Pashu straddles a particular and complicated divide in Without the King, Michael Skolnik’s intriguing documentary about the last kingdom in Africa, which opens 25 April at New York’s Quad Cinema. Introduced defending her father’s reign (“I think being a king is the hardest thing ever; you have to take the most criticism in the country”), she is also on her way to Hollywood, starting her freshman year at Biola University, a Christian school. As Pashu’s mother Queen LaMbikiza remembers being married at 16, Mswati’s first wife, the daughter imagines that her education in a foreign land will prepare her for being royal in the future. “We are the ones that have to change the country,” she says of her generation,” and toward that end, she seeks “knowledge.” Her father, in turn, expresses his pleasure in a way that indicates his conditioned detachment and performance for the camera (Pashu refers to him repeatedly as “the King”): “I have a kid that is going to university,” he smiles, “Of course I am very proud, the kid has been very good.”

As Pashu enjoys the “freedom” of campus life without security details and with an ATM card (“I’ve never used one,” she says, pressing buttons on the machine as the camera focuses on the sign above: “Need Cash?”). Her story in the abstract is soon reframed by experience. Stepping into the street outside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, she’s impressed by the traffic, the lights, the architecture: “I wish that Africa was like this as well,” she says, her sentences fracturing. “It just shows how much we still need to… It seems impossible… It wouldn’t even be good to reach this level…” She sighs and finishes with an assessment that is diplomatic and self-preserving: “You guys are doing good for yourselves.”

While Pashu processes her experience in the United States, Skolnik’s film also shows her father’s lavish and carefully orchestrated existence in Swaziland, and, in a third, broadly sketched section, the lives of various activists — Mphandhlana Shongwe organizing protests against the monarchy in Moneni Township, Siphiwe Hlophe’s work at an AIDS orphanage in Sibhovu Township, and Ntombi Nkosi, president of the Ngwane National Liberatory Congress Women’s League. With political parties banned under the kingdom’s constitution, activists must seek other means to make their voices heard.

The film’s structure is partly confusing (especially if you are unfamiliar with recent movements and struggles in Swaziland) and partly sly, as it sets the several stories in tense and telling contiguity. Mswati first appears as a child, making his first public speech when he became King in 1986: “I had baboons in my stomach,” he recalls of his nervousness. And yet, he tells his people, “Although my experience is short and I am new to this task, I have in my predecessors an example I can follow in sanctity and confidence.” 20 years later, his country is in increasing disarray, with over 70% of the population living in poverty and HIV/AIDS at a 42.6% prevalence rate (to provide a stunning comparison, the film notes, the U.S. has a 0.6% rate).

As the King insists on the importance of “maintaining our traditions,” in order to explain his family’s “seven royal residences, fleet of luxury cars, and large stake in real estate, media and sugar industries,” Shongwe laments his role as a dictator, the disparity between his opulence and his people’s destitution. Most people live on less than 63 cents a day and depend on World Food Programme rations to eat. Beset by drought and disease, they are also angry — precisely because the vaunted “traditions” demand their abjection. “We are at a level where some of the forces can’t be held back,” Shongwe says, huddled near a lamp in a mud-brick hut late at night. “Yesterday, I was prepared to die for the struggle. But today, I don’t want to die for the struggle. I want to kill for the struggle.”

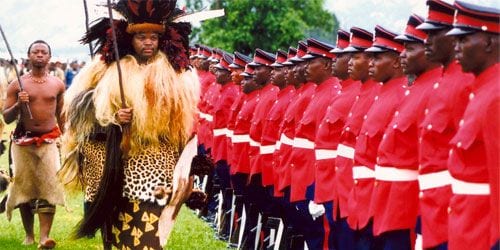

The struggle includes demands that the constitution be revised to include popular participation; as it stands, Mswati (who went to school in England before becoming King), appoints the prime minister and cabinet, and all judges. He also heads the military, visible at all public functions, including those where he invites “dialogue” on issues before he makes his decisions. The film doesn’t take up Swaziland’s international contexts (except to feature a brief bit of a speech by Stephen Lewis, Special UN Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa). Neither the King nor his critics speak to the large chunk of GDP premised on the Coca Cola Company, which exploits the nation’s cheap sugar and labor. The film does show, however, that the King employs force to oppress demonstrators.

Instead, the film’s recurring focus is HIV/AIDS, noting that in 2001, the King invoked the Umchwasho tradition, a ban on sex for all unmarried teenaged girls. For five years, this demographic wore tassles in public to identify them as virgins. Even as men are granted the power to decide whether or not to use condoms with their wives, women remain objects to be displayed and, in effect, traded. When Pashu returns home to lead the Reed Dance, an annual parade of 75,000 young virgins, from which her father selects his next wife (his own father had 110 wives; Mswati has 12 when the Reed Dance commences). Though Pashu smiles and dances expertly for the ceremony, she confesses later to the camera that she is troubled by the fact that her father took a 13th wife: “Having a new member of the family is always stressful, a greater division of love attention money.” Quietly, Pashu adds, “She’s younger than me, so you can imagine what that feels like.”

By film’s end, Pashu finds another direction for her energy, when she visits the AIDS orphanage and marvels at the children who celebrate her arrival. “I’m heartbroken because of what I’ve just seen and because the government just abandons this area. They have so much money and they could just do anything with it and they choose not to.” Pashu may or may not embody change, though Without the King provides the possibility: “We have to stand up as children,” Pashu insists. “I am the eldest f the king’s children and for the upcoming future generation. We need to have some kind of hope.” After so much hypocrisy and seemingly willful ignorance, Pashu at least articulates possibility. Whether she is as well versed in performance as her father, or whether she has the opportunity to push for such hope, remains to be seen.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)