What Makes Johnnie Ray a “Freak”? Musical Traces

Johnnie Ray launched his career with “Cry,” which was a radical pop song because it incorporated musical elements of black music that made it a pop and R&B hit. The song, written by Churchill Kohlman, was released October 1951, several years prior to civil rights landmarks such as the death of Emmett Till, Brown v. Board of Education, and the March on Selma that drew attention to the toll of racism and the promise of integration. The B-side of “Cry” is the highly sentimental “The Little White Cloud that Cried” and was atypical for white male pop in its themes of isolation and loneliness. Compared with most mainstream white male singers of the early 1950s, Ray was an anomaly, or, colloquially speaking, he was somewhat of a “freak.”

Ray defied masculine vocal styles and “white” vocal styles of the late 1940s and early 1950s. He was so highly influenced by R&B singing, especially black female singers like LaVern Baker, that he was mistaken for a black female singer when his voice was mistaken for that of a black female singer. Danny Kessler, head of Okeh Records Artists & Repertoire (A&R), told Ray’s biographer Jonny Whiteside, “I played the record for the sales force at Columbia and almost in unison they said, ‘We don’t think she’s gonna make it.’ They all thought I was pitching a girl who sounded like Dinah Washington! Finally I convinced them that she was a boy, and then I had to break the news that she was a white boy. I know they all felt that I had lost my head completely” (Whiteside 1994, 63). Ray’s R&B inflections and sentimental tone were apparently such a contrast to the typical sound of white male vocals at the time that he stood apart instantly on sound alone. He favored highly emotional songs like his 1951 hit “Cry,” and his vocal intensity was matched by a physical spasticity.

(The below YouTube performance is provided for readers of this excerpt – it is not part of Rocking the Closet.)

In the early 1950s Ray’s sentimental singing and dynamic concert style led to a barrage of nicknames (“Nabob of Sob,” “Prince of Wails”), variety show sketches, and song parodies (Stan Freberg’s “Try”), which he accepted with humor. As he told Billboard in 1952, “I get the biggest kick out of take-offs on me—particularly Stan Freberg’s record and the stuff that Jack E. Leonard and Sammy Davis Jr. do” (Martin 1952c, 19). Ray had to stand apart in some way if other artists felt compelled to coin these names. If he were a typical crooner, he would not have garnered this kind of attention.

Rock historian Charlie Gillett discusses Ray in his The Sound of the City as a transitional figure one step beyond Frank Sinatra and Frankie Laine, who capitalized on Sinatra’s pioneering audience aesthetic. According to Gillett, “Sinatra’s style involved audiences in his singing—and in him—as no previous singer had done, and stimulated devotion comparable to that previously aroused only by film stars like Rudolph Valentino…. Audiences expected singers to project themselves (or what was publicly known of their selves), and each listener wanted to feel as if the singer were singing to her (or him, if the listener was male) (Gillett 1996, 6). There was a succession of Italian American male singers who found success post-Sinatra, but Laine was a particularly successful follower. Gillett distinguishes Ray by noting that “in 1951, involvement rose to a new peak when another singer … inspired furores at airports, hotels, and backstage theatre doors—Johnnie Ray. In contrast to his predecessors, Ray lacked smoothness, precision of phrasing, or vocal control; instead, he introduced passionate involvement into his performance, allowing sighs, sobs, and gasps to become part of the sound relayed by the amplifiers”.

Gillett intends to contrast rock ‘n’ roll and pre-rock pop of the early 1950s, and in doing so he defines Ray as an almost purely contextual figure, “Even Johnnie Ray was hardly as remarkable as the enthusiasm of his supporters, or the distaste of his decriers, would suggest. Only in comparison with the generally emotionless music of the times, to which Ray, like Laine, were exceptions, could the silly and sentimental ‘Cloud’ have attracted anybody’s interest” (Gillett 1996, 6–7). His harsh summary is perhaps too broad in its reading of pre-rock music, but it addresses the distinctive emotionalism Ray brought to 1950s pop and his unique appeal to audiences.

Radio-TV Mirror, June 1953 (Public Domain / Wikimedia) (This photo is provided for readers of this excerpt – it is not part of Rocking the Closet.)

Some of the main elements of his musical appeal were his unique phrasings and the mechanics of his performing style. Rock historian Reebee Garofalo’s Rockin’ Out suggests that “early in the 1950s, the emotionally unhinged Johnny [sic] Ray could have provided Columbia with a way into rock ‘n’ roll. His uninhibited stage performances, during which he routinely ripped off his shirt, were at least in part the result of tutelage by LaVern Baker and her manager” (Garofalo 2005, 126). Here he refers to the influence of Baker, a black R&B singer who recorded many successful hit singles for Atlantic Records during the 1950s, on Ray. It is important to note, however, that various black musical figures directly influenced Ray’s performing style. Whereas most white crooners were trained in big-band singing before transitioning to solo careers, Ray had more diverse mentors. In their 2003 American Popular Music, Larry Starr and Christopher Waterman note, “Ray created an idiosyncratic style based partly in African American modes of performance, and in so doing paved the way for the rock ‘n’ roll stars of the later 1950s,” and this included being “the first white pop performer to remove his microphone from its stand and go down into the audience, seeking direct contact. His stage act was dynamic: Ray writhed, wept, and fell to his knees” (181). Other singers commonly associated with this kind of vocal intensity and physical emotion were black male performers like Jackie Wilson, James Brown, and Otis Redding.

Ray’s chief childhood vocal influences were gospel, hillbilly, jazz, and black popular music. Blues and jazz-influenced popular singers Kay Starr and Billie Holiday strongly influenced Ray (Whiteside 1994, 29, 32; Guild 1957, 49). Profiles in both Billboard and the Saturday Evening Post noted Ray’s roots as a performer on the Midwest club circuit including Detroit’s “black-and-tan” (or racially mixed) Flame Bar. Ray developed his chops for blues-oriented singing under the tutelage of blues singer Maude Thomas and years of singing at the Flame, where he developed a rapport with numerous black musicians and endeared himself to multiracial audiences (Martin 1952c, 16, 19; Whiteside 1994, 49, 51, 54). The Post noted, “It was here, in all probability, that Ray developed his phrasing and vocal style which are reminiscent of so many top-flight Negro blues singers” (Sylvester 1952, 112). After he scored his initial hits Ray proclaimed his attitude toward segregation in the self-penned 1953 Ebony story, “Negroes Taught Me to Sing.” Ray boldly expressed his outrage at Jim Crow laws and related to blacks when he noted, “Coming up the way I did—the hard way—and having been almost laughed out of existence ever since I was a skinny, unwanted kid, I know how it feels to be rejected,” and “they have an innate sympathy with the underdog and a delight in seeing a handicapper come from behind” (Ray 1953, 48, 56). Though some of Ray’s statements were simplistic, what stood out was the oddity of a white mainstream pop singer overtly identifying with and praising black culture at the time, and his open disapproval of racial segregation.

Few popular white musicians of his time took this kind of political stance openly. Though many white musicians would participate in the civil rights movement in the 1960s (Tony Bennett, for example), Ray’s article and statement were unusual (Raymond 2015b, 71, 197). As author of a book about the closet, I would argue that his ability to incorporate black musical elements and his comfort and acceptance among black musicians and audiences are notable for what such realities uncloseted. Notably, he demonstrated the constructed nature of racial differences and modeled possibilities in the entertainment world that could translate into daily life. I have yet to locate any record of fallout from his statement, especially since few whites probably read Ebony in the early 1950s. Nonetheless, it illustrates another way he stood out and remained viable commercially.

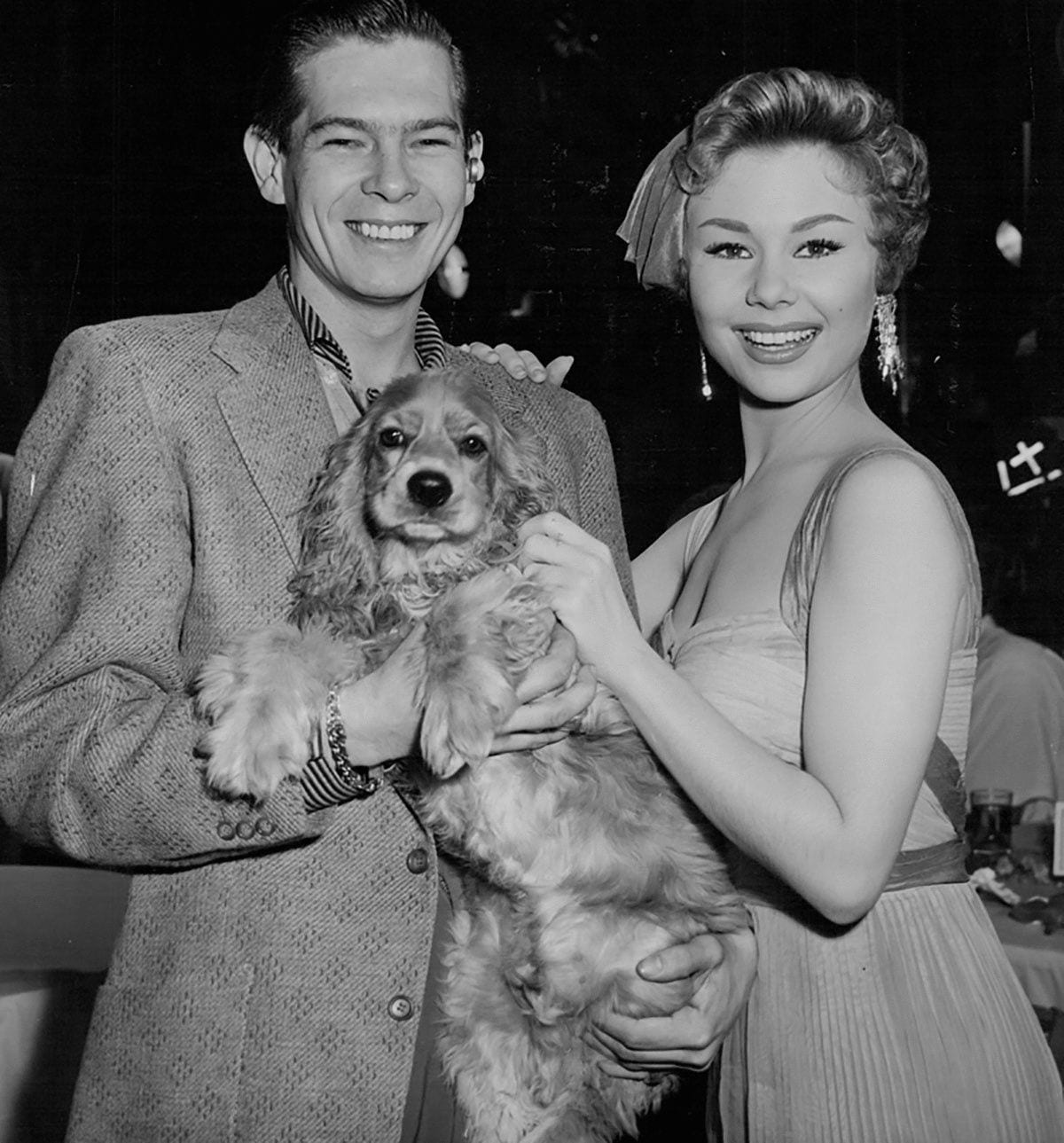

Johnnie Ray and Mitzi Gaynor, 1954 (Public Domain / Wikimedia) (This photo is provided for readers of this excerpt – it is not part of Rocking the Closet.)

Music critic Will Friedwald argues that in vocal terms, Ray “was indeed the first-ever crossover R&B star—the first white entertainer to work in the contorted, hyphenated manner (in other words, “Cah-ry-hi” instead of “cry”) that characterized rhythm and blues and then doo-wop and early rock. That style of singing was already highly exaggerated and mannered, yet Ray was even more so…. As the first white R&B headliner, he signified the first time many middle Americans had heard even a vague imitation of ‘race’ music” (Friedwald 2010, 684). The nature of his performing style and vocal approach has culminated in diverse opinions about Ray’s relationship to rock ‘n’ roll. Gillett defines Ray as a slight contrast to pre-rock crooners but not as a rock ‘n’ roll performer; Garofalo posits him as a would-be rock ‘n’ roller; Starr and Waterman more overtly define him as “a crucial link between the crooners of the postwar era and the rock ‘n’ roll stars of the later 1950s” (181). Whiteside and Friedwald suggest a slight variation on this connection by defining him as a bridge between Al Jolson and Elvis Presley (Whiteside 1994, 117; Friedwald 2010, 683). Whiteside states,

From the cornerstone of blackface (the earliest commercial 50–50 blend of African rhythm and European melody) popular music grew in entirely new and different ways. The general acknowledgement of such personal freedom brought with it a sense of individual power. That response led to a craving for the long denied taboo of primal independence. Jolson brought it to the Twentieth Century; Johnnie tore off the theatrical mask and offered it to people; Elvis gave it a threateningly tangible accessibility. (Whiteside 1994, 117)

Ray’s differences from the mainstream made him a phenomenon in a decade fascinated by novelty. For example, the anthology Widening the Horizon (1999), by Philip Hayward, documents the commercial rise and social impact of postwar “exotica,” defined as “music which features aspects of melodic and rhythmic structure, instrumentation and/or musical colour which mark a composition as different from established (western) musical genres (while still retaining substantial, recognizable affinities to these)”. Les Baxter, Martin Denny, Arthur Lyman, Korla Pandit, and Yma Sumac are among the musicians whose “exotic” sounds reached the commercial mainstream, peaking commercially from the early 1950s through the mid-1960s. Though Ray’s music certainly fits within Western musical traditions, it was just different enough to stand out in a decade when America was actively reinventing itself. Billboard published a four-part series on Ray’s rapid rise from obscurity to success. The second installment documented the numerous disk jockeys and club bookers who claimed to have discovered Ray. Key to this story is the line, “While Ray was working in the Ohio territory, several musicians and disk jockeys saw in him the big-time touch” (Martin 1952a, 19). The pervasive sense that he was “different” made Ray a unique commercial figure, and marketing him effectively was important. The appeal of “Cry” to pop and R&B listeners solidified him as the rare white performer with white and black appeal. In this sense, his ambiguous aural identity was beneficial.

Excerpted from Rocking the Closet: How Little Richard, Johnnie Ray, Liberace, and Johnny Mathis Queered Pop Music by Vincent Stephens (footnotes omitted). Used with the Permission of the University of Illinois Press. Copyright 2019 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)